Carting Away the Oceans

Introduction

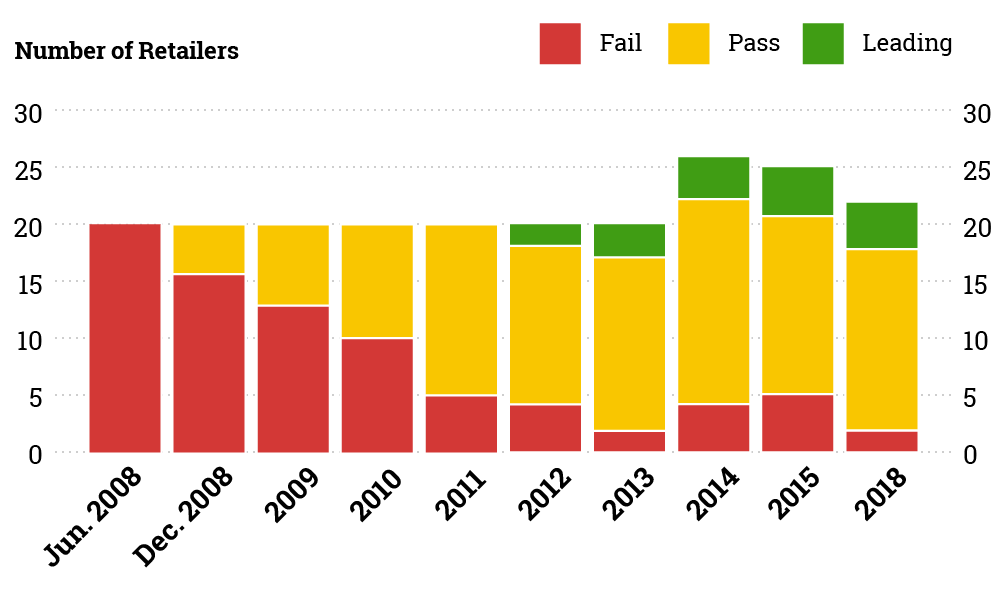

In June 2008, Greenpeace published the first edition of Carting Away the Oceans, and evaluated 20 major U.S. grocery retailers on seafood sustainability. By documenting current practices and educating retailers about the impacts of their seafood sales on marine life and our oceans, we sought to raise consumer awareness and collectively encourage retailers to source only sustainable seafood. At that time, the vast majority of retailers were concerned with price and quality, not seafood sustainability. Unsurprisingly, all 20 retailers failed in the first evaluation. Ten years later, in this tenth edition of Carting Away the Oceans, 20 out of 22 retailers have achieved at least passing scores.

We would like to acknowledge the extensive contributions of Greenpeace supporters and volunteers, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), scientists, governments, retailers, suppliers, and the press. Through dialogue, collaboration, and a persistent vision for a better future for our oceans, together we have achieved a great deal over the past ten years. Nonetheless, the work over this next decade is critical to ensuring healthy oceans teeming with marine life, where seafood workers are treated fairly, and coastal fishers are able to provide for their families without suffering exploitation from industrial fishing fleets. To achieve this vision for marine life and people, we must stay focused and act with a sense of urgency.

As fish stocks decline from overfishing, industrial fleets expand, and demand increases for cheap seafood, some companies are motivated to employ cheap or forced labor and to fish illegally.[1] Furthermore, a convenience-driven, throwaway culture is exacerbating a global plastic pollution crisis in our oceans. As our planet faces greater environmental threats, more and more people are coming together to demand real social and environmental leadership from corporations, and to create a better future. This moment requires marked action. As we have urged in every Carting Away the Oceans, retailers should use their brand and buying power now to create a different world for our oceans and humanity.

Timeline of Notable Milestones Since June 2008

Greenpeace has evaluated U.S. grocery retailers on sustainable seafood since 2008. This timeline highlights some of the milestones and accomplishments that demonstrate progress in this sector over time.[i]

June 2008: Greenpeace releases its first Carting Away the Oceans report. Not a single retailer received a passing score. Sustainable seafood was not even on the radar of many retailers, and orange roughy and Chilean sea bass commonly appeared in seafood cases across the country.

December 2008: A six-month update of Carting Away the Oceans is released to reflect swift progress by several retailers. Nine retailers drop one or more red list items, including shark, bluefin tuna, orange roughy, and Chilean sea bass. Wegmans and Whole Foods post new sustainable seafood standards online.

June 2009: The third edition of Carting Away the Oceans is released, with Wegmans, Ahold, and Whole Foods in the lead, and H-E-B, Price Chopper, and Meijer in the back of the pack. Target and Walmart have both dropped orange roughy and Wegmans asks the U.S. State Department to address illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing.

January–March 2010: Target announces that it will stop selling all farm-raised salmon (which it unfortunately reintroduces in 2017). Following a Greenpeace campaign, Trader Joe’s agrees to implement sustainability measures throughout its seafood operations, and stops selling orange roughy.

April 2010: In the fourth edition of Carting Away the Oceans, half of the 20 retailers evaluated receive passing scores, and more than half have sustainable seafood policies. Target, Wegmans, and Whole Foods lead the pack, while Winn-Dixie, Meijer, and H-E-B are dead last. Greenpeace launches a campaign on Costco to clean up its sourcing.

Early 2011: Costco, Harris Teeter, H-E-B, and Safeway discontinue orange roughy, three more retailers drop Chilean sea bass, and Price Chopper discontinues shark. Following Greenpeace’s campaign, Costco agrees to remove more than half of its red list seafood items, pursue better practices in aquaculture, and assume a leadership role to develop a sustainable global tuna industry. Safeway and Wegmans publicly call for a marine protected area in the Ross Sea. (Today, under an international agreement signed in 2016, this intact ecosystem is now protected from all commercial fishing for 35 years.)

April 2011: Five new retailers receive passing scores, and only five retailers fail in the fifth edition of Carting Away the Oceans. Safeway, Target, and Wegmans lead the pack, while SUPERVALU, Winn-Dixie, and Meijer remain in last place.

April 2012: By the sixth edition of Carting Away the Oceans, Safeway and Whole Foods are the first retailers to earn a green ranking and the only two profiled retailers selling sustainable private label canned tuna. Wegmans ranks third, and the three worst performers are SUPERVALU, Publix, and Bi-Lo/Winn-Dixie. The sale of four top-tier red list species across profiled retailers has dropped precipitously since 2008: shark (down 78%), orange roughy (down 75%), hoki (down 71%), Chilean sea bass (down 50%). A&P, Ahold, ALDI, Costco, Meijer, Target, and Walmart do not sell any of these species.

May 2013: In the seventh edition of Carting Away the Oceans, Whole Foods, Safeway, and Trader Joe’s lead the pack in the green category, while Kroger, Publix, and Bi-Lo continue to scrape the bottom. Walmart has introduced FAD (fish aggregating device)-free skipjack and pole and line albacore tuna in more than 3,000 stores nationwide, and ALDI, H-E-B, Meijer, Trader Joe’s, and Whole Foods have publicly committed to avoid selling genetically engineered (GE) salmon.

May 2014: In the eighth edition of Carting Away the Oceans, the four green rated companies are Whole Foods, Safeway, Wegmans, and Trader Joe’s and the four failing companies are Publix, Save Mart, Bi-Lo, and Roundy’s. Every other retailer achieves a passing score. Safeway and Kroger join more than 60 other retailers pledging not to sell GE salmon. Hy-Vee debuts in fifth place, selling sustainable private label canned tuna along with Whole Foods, Safeway, and Trader Joe’s. Greenpeace demands action from retailers on labor and human rights abuses and IUU fishing.

June 2014: A UK Guardian investigation reveals forced labor in the supply chain of the Thai shrimp industry’s biggest supplier, CP Foods, naming Walmart, Costco, and ALDI as customers of shrimp supplied by CP Foods.[2]

June 2015: In the ninth edition of Carting Away the Oceans, Whole Foods, Wegmans, Hy-Vee, and Safeway earn a green rating, while Southeastern Grocers, Roundy’s, Publix, A&P, and Save Mart fail. Costco and Target begin selling private label sustainable canned tuna. Whole Foods, Wegmans, Hy-Vee, Safeway, Ahold, and Giant Eagle call on Congress to pass tougher legislation to stop IUU fishing.

December 2015: An Associated Press investigation reveals child and forced labor was used in Thai Union’s shrimp supply chains.[3] Kroger, Albertsons, Whole Foods, and Walmart are mentioned as examples of where tainted seafood might have ended up (in either shrimp or pet food products), to demonstrate the significant risks for all retailers regarding poor traceability.

2016: Greenpeace’s global campaign on tuna giant Thai Union is underway. In April, Greenpeace launches a campaign on Walmart to improve its canned tuna. Several U.S. retailers continue focusing, or begin to focus, on canned tuna. In December, Greenpeace’s Turn the Tide report[4] documents the risks associated with transshipment at sea, including a significant risk of products sold by major U.S. retailers being linked to IUU fishing and human rights abuses.

2017: In March, Mars and Nestlé announce strong measures to address transshipment at sea. Several retailers have released public shelf-stable tuna policies, including, Whole Foods, Hy- Vee, ALDI, Giant Eagle, Wegmans, and Albertsons. Whole Foods becomes the first U.S. retailer to commit to sell only sustainable canned tuna (private label and national brands). By the release of Greenpeace’s second U.S. Tuna Shopping Guide[5] in April, ALDI, Giant Eagle, Ahold Delhaize, Kroger, SUPERVALU, and Southeastern Grocers are developing or selling sustainable private label canned tuna products. In July, Thai Union commits to a series of environmental and social reforms, that will transform its U.S. and global tuna supply chains.

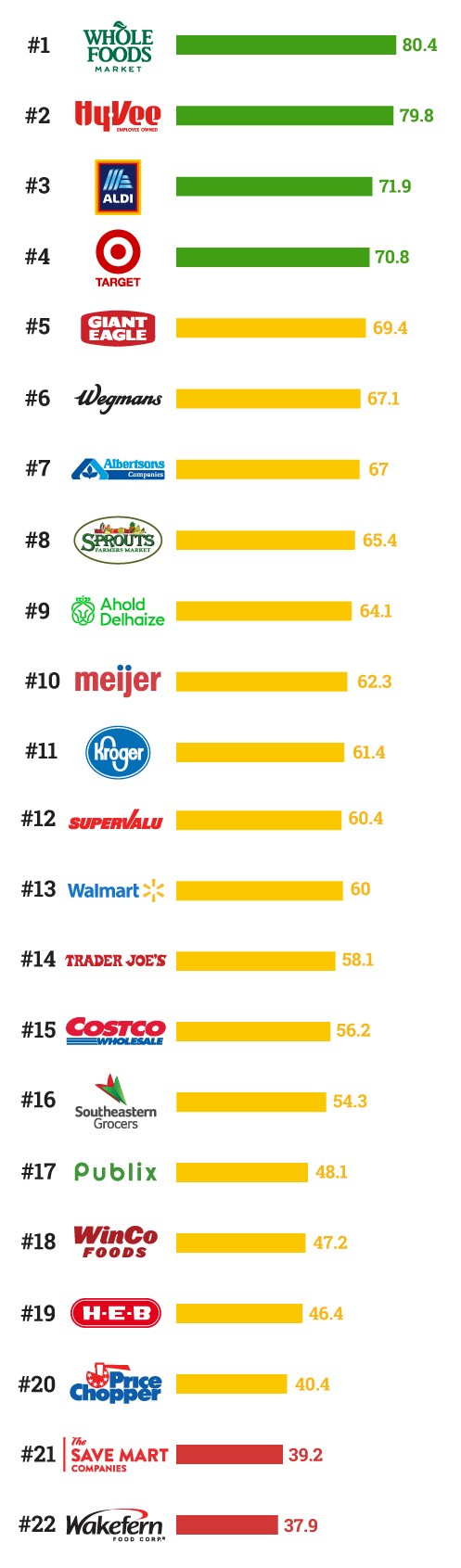

August 2018: Greenpeace releases its tenth edition of Carting Away the Oceans, where 90% of profiled companies receive passing scores, versus all failing in 2008. Whole Foods, Hy-Vee, and ALDI hold the top three ranks as Price Chopper, Save Mart, and Wakefern score the lowest. Amid major improvements over the last decade, new threats persist from labor and human rights abuses, climate change, and plastic pollution. The next decade is critical for ocean health and humanity.

Carting Away the Oceans 10: Significant Findings

Following mergers, acquisitions, and bankruptcies, this year’s edition assesses 22 U.S. retailers with a significant nationwide or regional presence, including one newly profiled retailer (Sprouts Farmers Market, or “Sprouts”). Ninety percent of the retailers achieved at least a passing score.

- Whole Foods remains the top-ranked retailer following the release of its shelf-stable tuna policy last year. After Amazon’s acquisition of Whole Foods, questions remain as to whether Amazon will follow the grocer’s lead on sustainable seafood.

- Hy-Vee (ranked 2nd), improving on shelf-stable tuna and with several advocacy initiatives, takes Wegmans’ place near the top. Wegmans dropped four spots to 6th, in part because of its unfortunate reintroduction of orange roughy and its troubling decision to source farmed Pacific bluefin tuna for special events.

- By continuing to implement their policies and seize advocacy opportunities, ALDI (ranked 3rd) and Target (4th) moved into the green category. Giant Eagle’s (5th) years-long focus on sustainable seafood is bearing fruit: the retailer leapt six spots to round out the top five.

- ALDI (ranked 3rd), Giant Eagle (5th), Wegmans (6th), and Sprouts (8th) have public policies with requirements regarding transshipment at sea for tuna. Whole Foods (1st), Hy-Vee (2nd), and Meijer (10th) are the only profiled retailers that fully source pole and line and/or FAD-free tuna for their own brand shelf-stable products.

- None of the profiled retailers have major, comprehensive commitments to reduce and ultimately phase out their reliance on single-use plastics. Among the largest U.S. retailers by revenue, Walmart, Kroger, Costco, Ahold Delhaize, Albertsons, and Amazon must urgently address their contribution to the plastic pollution crisis.

- Following its acquisition of Safeway, Albertsons Companies’ (“Albertsons,” ranked 7th) public commitments and advocacy initiatives landed it as the highest ranked among the nation’s five largest (by revenue) retailers, and the company is building upon Safeway’s legacy of sustainable seafood initiatives. Ahold Delhaize (9th) and Kroger (gained seven spots to 11th) are close behind, while Walmart (13th) dropped one spot and Costco’s (15th) rank remains unchanged.

- Newly profiled Sprouts (ranked 8th) has a new sustainable seafood policy, with plans to source 100% pole and line shelf-stable tuna and to phase out red list species.

- Save Mart (ranked 21st), Publix (17th), Southeastern Grocers (16th), Kroger (11th), and Giant Eagle (5th) are the most improved retailers, respectively. Southeastern Grocers and Publix both received passing scores for the first time ever. Although Save Mart failed in this report, as it implements its new seafood policy, it should continue to improve.

- While other retailers made strong gains, Trader Joe’s (ranked 14th) dropped seven spots following a lack of initiatives and customer engagement on sustainable seafood. Price Chopper (20th) dropped six spots, underperforming on initiatives and transparency, while Wakefern (22nd) dropped five spots to scrape the bottom of the rankings.

The Modernization of Grocery Retail

There has been a dramatic change in grocery retail since the last edition of Carting Away the Oceans in 2015. Consolidations continue and formerly profiled companies have either merged or gone out of business.

Several trends are emerging in the wake of Amazon’s acquisition of Whole Foods, as competitors seek to remain relevant in this new era of grocery retail.[6] Retailers are partnering with delivery services to offer faster, even two-hour, delivery. Walmart acquired Jet.com, Target acquired Shipt, retailers from Costco to Albertsons offer delivery through Instacart, and Ahold Delhaize’s Peapod, which launched decades ago, is offering price cuts and promotions to remain competitive. At the store level, retailers are investing in modernized layouts, signage, and product packaging, as many open smaller-format stores for urban millennials. Some are also integrating tech solutions that offer convenient ways to shop and pay for groceries (e.g., pick up pre-bagged groceries, Apple Pay). A key strategy in staying competitive, employed by the likes of Trader Joe’s, ALDI, and Costco, involves a focus on private label products, especially as millennials and urban shoppers increasingly trust these over national brands.[7],[8],[9]

As part of this technological modernization effort, some retailers are working with organizations or companies that can bolster a retailer’s seafood traceability, to avoid unsustainable or unethically sourced seafood (e.g., Whole Foods, Ahold Delhaize, and Albertsons with Trace Register; Publix, Walmart, and Giant Eagle with Sustainable Fisheries Partnership (SFP) for its Ocean Disclosure Project (ODP)). While this is a welcome trend, Greenpeace cautions against the public relying too heavily on such resources for information. In the case of ODP, the data are all self-reported, focus only on wild-caught seafood, and even then, do not encompass the entire inventory.[10] Nonetheless, Greenpeace acknowledges such efforts as a great first step toward greater seafood traceability and transparency.

Drowning in Plastic

Across the board, retailers are severely lagging in their efforts to tackle single-use plastic packaging. The equivalent of one garbage truck of plastic enters our oceans every minute,[11] and with plastic production set to double in the next 20 years—largely for packaging—the threats to ocean biodiversity and seafood supply chains are increasing. The United Nations (UN) describes it as a potential “toxic time-bomb.”[12] Single-use plastics are devastating our oceans, and retailers must take responsibility for their contribution to this global crisis (see Plastics Are Devastating Our Oceans). Retailers in the United Kingdom[13] and the Netherlands[14] are making significant changes and commitments toward reducing or eliminating the use of plastics in their operations. It is time for U.S. retailers to swiftly and comprehensively reduce and eventually phase out single-use plastics.

Struggling to Uphold Labor and Human Rights Standards

The year 2018 has seen a continued focus on labor and human rights in the seafood industry, including several reports from organizations like Human Rights Watch,[15] International Labor Rights Forum (ILRF),[16] Greenpeace,[17] and Oxfam.[18] Behind the Barcodes, a recent Oxfam report, even profiled some of the same supermarkets in this report across four categories: transparency, workers, farmers, and women. It found that all six U.S. retailers[ii] profiled outright failed, and had “barely shown any awareness,” in particular regarding transparency in their supply chains and gender inequality issues.[19]

Many in the industry are part of initiatives, such as the Seafood Task Force. While such fora can facilitate improvements, this initiative seems to have stalled out.[iii],[20] For meaningful changes to occur in Thailand, Taiwan, and other key regions, the Task Force and its member companies must step up their commitment by encouraging the Thai and Taiwanese governments to make it legal for migrant workers to organize and lead trade unions, and to ensure that International Labour Organization (ILO) conventions 87, 98, 108, and 188 are ratified and fully implemented.[21] Fortunately, other initiatives like the newly formed Fishers’ Rights Network (FRN)[22] are working to stop exploitation and abuse in the Thai fishing industry, and calling for bold action from the Thai government. Supported by the International Transport Workers’ Federation, the FRN is helping workers to organize and campaign to improve the wages, working conditions, and labor rights of all fishers in the Thai fishing industry.

In May, Greenpeace East Asia reported on systemic problems in Taiwan’s distant water fishing fleets, including labor and human rights abuses linked to one of the world’s largest seafood traders, Fong Chun Formosa Fishery Company (FCF).[23] Many large U.S. retailers do business with FCF and should act quickly to evaluate the social responsibility and sustainability of any seafood supplied by FCF, including calling on FCF to make far-reaching reforms.[iv] Retailers must leverage their long-term supplier relationships—whether with FCF or another supplier—to improve problematic operations wherever possible. However, if a supplier cannot demonstrate swift and effective action to eliminate problems once they have been identified, then retailers or other customers should terminate their relationship with that supplier.

Most eco-certification schemes either insufficiently address or outright ignore labor abuses and seafood worker treatment in the supply chain,[24],[25],[26] and even social certifications have failed to create the systemic changes needed.[27] Rather than doubling down on inherently flawed certification schemes or relying only on corporate codes of conduct and internal or external audits, industry and NGOs must reconsider whether this approach is indeed working. Greenpeace encourages all profiled retailers and their suppliers to aim higher and instead support ILRF’s call to action[28] to hold companies and retailers accountable through legally binding commitments and enforceable agreements with trade unions and workers’ organizations that put workers’ rights, legal fishing, and environmental sustainability front and center.

“Certified” Sourcing and Troubling Policy Developments

While retailers have collectively phased out many red list species over the past decade, amid controversial Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) certifications of orange roughy and Chilean sea bass, some retailers may be eager to begin sourcing them again. Greenpeace strongly cautions against this potential transgression. Sometimes a species should not be commercially available, despite what the MSC or any other certification scheme says; most certifiers face strong industry pressure and have a financial incentive to certify fisheries or farms. While Greenpeace recognizes there is some value to certifications, retailers cannot solely rely on them given outstanding concerns.[29],[30],[31],[32],[33],[34],[35]

Meanwhile, in U.S. waters, trouble is brewing with the Trump administration’s repeal of the National Ocean Policy[36] and the U.S. House of Representatives’ approval of a bill that significantly weakens conservation measures in the Magnuson-Stevens Act.[37],[38] This should concern every retailer that sources from U.S. fisheries, and those retailers touting the strength of sourcing from U.S. fisheries in their public policies. Retailers must advocate for strong ocean protections and science-based fisheries management both domestically and abroad.

Tuna Improvements and Challenges

Following a global campaign that included extensive U.S. retailer engagement, Thai Union responded to serious supply chain concerns (i.e., environmental, labor, and human rights). Thai Union, the world’s largest tuna processor, has developed a comprehensive new policy and program of change, demonstrating to the wider tuna and seafood industries what is possible if a company is willing to set a higher bar.[39]

In light of similar issues linked to its supply chains, FCF should now do the same. It is troubling that FCF touts sourcing MSC certified tuna (which, including the aforementioned concerns with MSC, only partly covers some of its operations) and has yet to apply its sustainability and social responsibility fisheries policies to all of its products. FCF must work alongside its suppliers to eliminate seafood that is associated with labor or human rights abuses. As one of the world’s largest tuna traders, this would help block tainted products from entering several key markets. FCF must assess all of its supplying vessels and prioritize auditing companies that are historically linked to IUU fishing or labor abuses. Retailers should move quickly to seek assurances and evidence that the seafood they buy from FCF is not linked to environmental destruction or labor abuses.

The tuna industry is fraught with transshipment at sea, where smaller boats refuel, restock, and transfer catch onto larger cargo vessels. This practice is often used to traffick workers who have no means of escape, turning fishing boats into floating prisons, and enabling vessels to hide illegally caught fish and mistreat crew members.[40],[41] Many retailers require tuna supplied by International Seafood Sustainability Foundation (ISSF) member companies, although this will not sufficiently address high-risk practices like transshipment at sea with longline vessels[v] or ensure sustainable tuna.[vi] Fortunately, some companies are taking action, including Thai Union,[42] Nestlé,[43] Mars,[44] Aramark,[45] ALDI,[46] Wegmans,[47] Giant Eagle,[48] and Sprouts.[49]

Retailers are also moving toward sustainable shelf-stable tuna. In 2011, Whole Foods was the first U.S. retailer to sell private label sustainable canned tuna, and in 2017, it was the first U.S. retailer to commit to sell only sustainable canned tuna across its entire private label and national brands. (Indeed, Whole Foods has effectively rendered the transshipment at sea issue moot, in that it only sources one-by-one caught tuna that avoids this problematic practice altogether.) In 2015, six retailers profiled in this report had sustainable private label canned tuna products; today, that number has nearly doubled to eleven, with additional retailers expected to launch products in the near future. As retailers continue to make improvements on their private label sourcing, they should also demand improvements from national brand suppliers and traders (like FCF), address problematic transshipment at sea, and advocate for improved management by regional fishery management organizations (RFMOs).[50]

Where We Go from Here

Despite the challenges we face, the past ten years have demonstrated that several retailers are willing and able to make significant improvements, to advocate with suppliers, governments, and industry laggards, and to take action—even when difficult. We will need this enthusiasm more than ever over the next decade, and urge retailers to use their brands, buying power, and influence to do what is right for our oceans and for future generations.

Companies Evaluated & Methodology

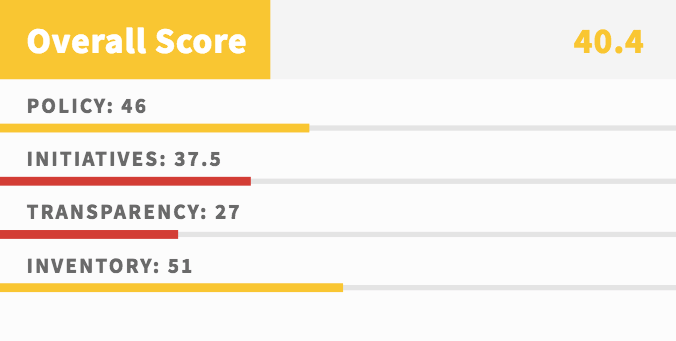

This report evaluates the seafood sustainability of 22 U.S. retailers[vii] in four key areas: policy, initiatives, labeling and transparency, and inventory. Each company received an identical survey reflective of the four scoring criteria, along with advance notice of the survey and context about this assessment, and was given approximately seven weeks to complete it. This year had a high rate of survey participation among profiled retailers: only Publix, H-E-B, and Wakefern declined to participate in the survey process.

Greenpeace also used publicly available information (e.g., websites, annual reports, industry press) to evaluate companies.[viii] While some profiled companies may have internal sustainable seafood initiatives, Greenpeace is unable to assess initiatives for which it has no data.

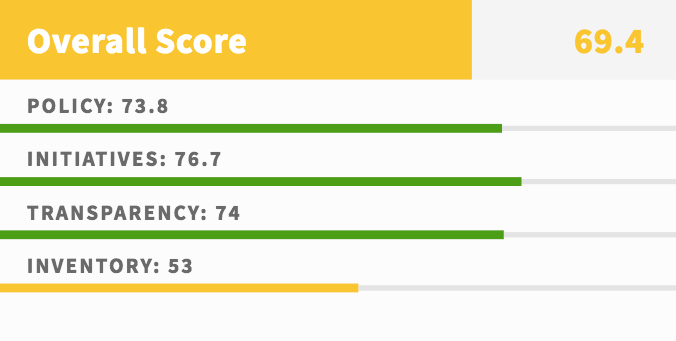

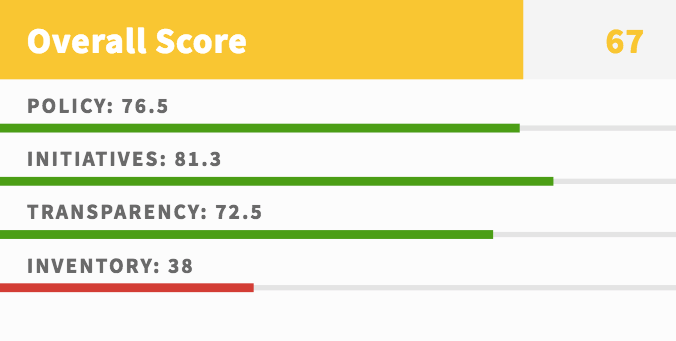

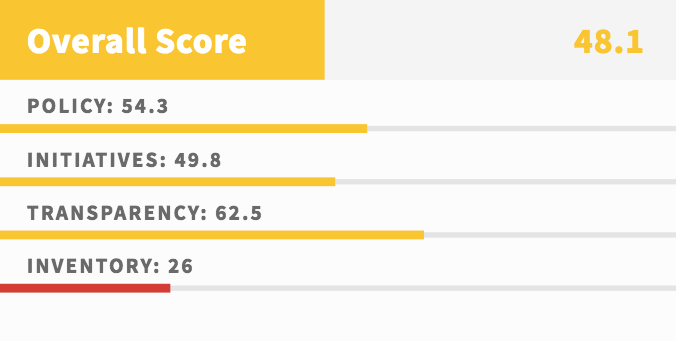

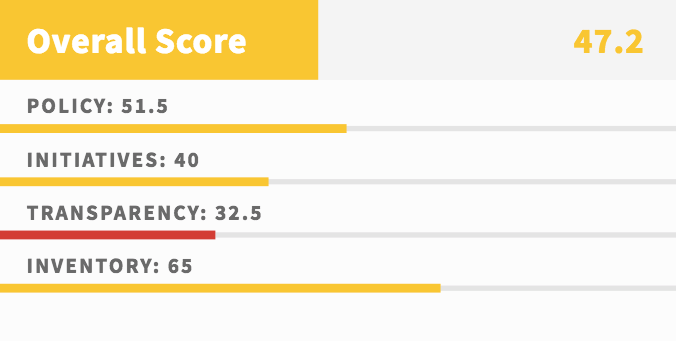

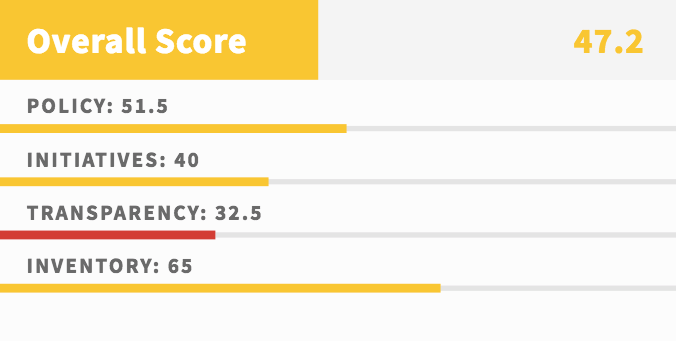

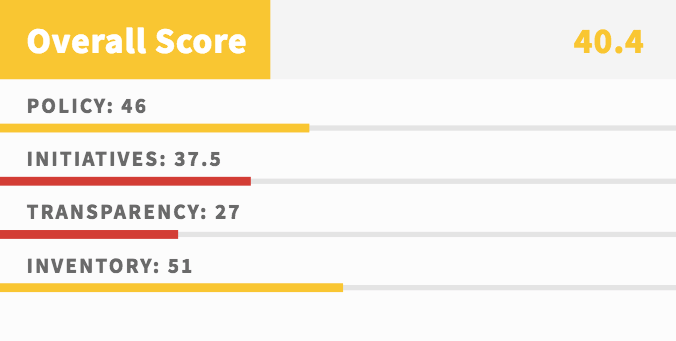

Surveys were scored independently and consistently. After extensive review of independent findings among the scoring team, companies received a score for each criterion and an overall score (a weighted average of all four criteria). Each company profile features its score for each of the four criteria and its overall score (on a 100-point scale). Retailers are ranked based on their overall score, where below 40 is failing (red), 40 to 69.9 is passing (yellow), and above 70 is leading (green). Each company is encouraged to meet with Greenpeace to discuss its results and Greenpeace’s recommendations.

Seafood Sustainability Scoring Criteria

1. Policy

The policy score reflects the system that the company has in place to govern its purchasing decisions and avoid supporting destructive practices. To lead in this category, a retailer would need to establish and enforce rigorous standards to responsibly source wild-caught and farm-raised seafood across the fresh, frozen, and shelf-stable categories.

2. Initiatives

The initiatives score evaluates a retailer’s efforts to improve fisheries management through policy and market interventions (e.g., refuse to buy tuna transshipped at sea; take measures to prevent IUU fishing; advocate for reforms with RFMOs; require suppliers to source only sustainable, ethical shelf-stable tuna; engage suppliers to improve their operations; work with groups to publicly promote sustainable seafood and protect workers’ rights). Retailers that have taken action to assess and reduce their plastic footprint, particularly with regard to single-use plastics, earn bonus points in this category.

3. Labeling and Transparency

This score evaluates a retailer’s transparency (e.g., online and in-store communication, vessel- or farm-to-shelf traceability). Equally important is whether retailers call on their suppliers to be transparent, particularly about where and how they catch or farm seafood. For customers, some companies present the data at the point of sale, while others opt to make the data accessible online. The best retailers do both, and a leader in this category would go to considerable lengths to educate its customers about the seafood they buy and the impacts of their choices.

4. Inventory (Red List)

This score evaluates each retailer’s seafood inventory across 26 commonly sold species. Greenpeace benchmarked each retailer’s inventory against the Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch recommendations, and considered whether a retailer mitigates sourcing concerns (e.g., engaged in a rigorous fishery improvement project (FIP) or aquaculture improvement project (AIP)).[ix]

Performance Badges

Category Winner – Awarded to each of the four category winners: Policy: Whole Foods; Initiatives: Hy-Vee; Labeling and Transparency: Hy-Vee; and Inventory: Trader Joe’s.

Canned Tuna – Awarded to the three retailers that sell only sustainable private label canned tuna: Whole Foods, Hy-Vee, Meijer.

Improvement – Awarded to the five most improved retailers (based on overall score, not relative ranking) since the previous report, in the following order: The Save Mart Companies, Publix, Southeastern Grocers, Kroger, Giant Eagle.

Wrong Way – Indicates the five retailers whose score dropped more than 0.1 points since the previous report, in this order from biggest to smallest drop: Price Chopper, Wakefern, H-E-B, Trader Joe’s, Wegmans.

Plastics Are Devastating Our Oceans

Retailers Failing on Plastics

The flow of plastics into our environment has reached crisis levels, and the evidence is most clearly on display in our oceans. The equivalent of one garbage truck of plastic enters our oceans each minute.[51] A recent study estimated that there may be more than 50 trillion pieces of plastic in our oceans,[52] and according to the UN, ocean plastic causes the deaths of hundreds of thousands of marine animals each year.[53] A 2015 study that analyzed the digestive tracts of fish sold in the United States and Indonesia found microplastic contamination in about 25% of the seafood sampled.[54] A 2017 study found substantial microplastic contamination in municipal tap water in every region of the world.[55] Every minute, one million plastic bottles are purchased worldwide,[56] and with plastic production set to double in the next 20 years—largely for plastic packaging—the threats to ocean biodiversity and seafood supply chains are increasing. The UN describes this as a potential “toxic time-bomb.”[57]

For this year’s assessment, we asked retailers what steps they have taken to address their plastic footprints. Unfortunately, most retailers have done far too little given the scope of the problem. Walmart’s 2025 goal of 100% recycled content for its private label packaging is the epitome of an outdated, ineffective strategy that many retailers currently employ. We cannot recycle our way out of this problem: less than 10% of plastic is recycled in the United States[58] and only 14% globally.[59] As it slowly degrades, plastic becomes more dangerous—breaking down into smaller pieces that are eaten by birds, whales, turtles, and other marine life; ending up in our drinking water, salt, and food, raising significant health concerns; and even contaminating the air we breathe in the form of microplastic particles.[60]

We can no longer afford to use plastic materials that last forever to make products that we use once and throw away. Throwaway packaging, straws, utensils, bags, and other single-use plastic items are choking our waterways and polluting our environment. That is why Greenpeace, alongside more than 1,000 organizations in the Break Free From Plastic movement,[61] is calling on retailers to set ambitious goals to quickly phase out single-use plastics. Without immediate action, the increasing quantity of plastics in our oceans will have severe consequences for biodiversity and human food and water safety.

Consumer Trends

Concern about plastic pollution is growing rapidly. A 2018 Ipsos survey on global views on the environment found that more than half of global respondents would reuse their disposable items to help cut down on waste.[62] Among American millennials, plastic pollution is now perceived to be a threat on par with oil spills, which has long been their top concern. Further, millennials expect action: 64% of millennials surveyed believe that we are likely to make progress in reducing the flow of plastic pollution into our oceans in the next five years.[63]

Many businesses are responding. In January 2018, UK retailer Iceland became the first major supermarket chain to commit to dropping plastic packaging from its own brand products. McDonald’s pledged to drop Styrofoam cups and packaging by the end of 2018, Starbucks announced it will be getting rid of plastic straws, and IKEA is phasing out single-use plastics. Bon Appétit Management Company was the first U.S. institutional foodservice company to make a public commitment, banning plastic straws, and in July, Aramark announced its ambitious plan to reduce single-use plastics across its global operations.

As other retail and foodservice sectors take action on single-use plastics, U.S. grocery retailers largely remain silent. As the five largest U.S. retailers, Walmart, Kroger, Costco, Albertsons, and Ahold Delhaize have an added responsibility to act immediately; however, all retailers must move swiftly to address the plastics crisis, starting with public commitments and time-bound policies to reduce their single-use plastic footprints.

Policy Changes

Governments at all scales are taking action globally. Plastic pollution tends to be a non-partisan issue in the United States, as evidenced by the ban on microbeads passed by Congress in 2016—one of the very few progressive environmental laws passed in recent years. California, Puerto Rico, and American Samoa have banned plastic bags, and a New York bag ban looks inevitable. Baltimore has outlawed Styrofoam, Seattle is getting rid of plastic straws, and other new laws to limit single-use plastics are being planned and debated in towns and cities nationwide.

France banned plastic plates and cutlery in 2016, and the European Union is considering more sweeping measures. Plastic bag bans are in effect in more than a dozen African countries, and India and Costa Rica are getting rid of single-use plastics altogether. Taiwan has announced it will begin banning plastic straws and several other single-use plastic items by 2019. In this global climate of rapid regulatory change, a strong business case is emerging for corporations to come together and support legislation to phase out throwaway plastics.

Alternatives

Over previous decades, plastic has become a very common part of our lives. Fortunately, there are several complementary approaches that can help move companies away from single-use plastics.

For many products, the answer is relatively straightforward: replace single-use plastic items like shopping bags, cutlery, and straws with reusable items made from more sustainable materials. Unnecessary packaging can simply be discontinued, saving money and avoiding ridicule from customers who do not want individually wrapped oranges, potatoes, cucumbers, or bananas. For most products typically sold in plastic packaging, there are alternatives in glass, aluminum, or cardboard. Better yet is the trend toward bulk sales, plastic-free aisles, and other new approaches to product delivery that do not rely on single-use packaging at all.

Bioplastics and biodegradable plastics may play a role in some cases, but often bring sustainability concerns of their own and have not yet proven to be sustainable alternatives at scale. Bioplastic implies that some or all of the source material is from plants, but carries no guarantee of sustainability—and in some cases still includes fossil fuels. Many so-called biodegradable materials do not break down at temperatures or light levels typically found in the ocean. Additionally, studies show that people are more likely to discard bioplastics in the belief that they will readily biodegrade.[64]

Time for Action

With alarming new scientific studies being published weekly, it is clear that our current reliance on single-use plastics is unsustainable for our planet’s health as well as our own. A major course correction is needed, and single-use plastics must be phased out. Greenpeace calls on retailers and their suppliers to take the following actions in 2018:

1. Analyze

What is your single-use plastic footprint? How much of each type of plastic do you sell, and in what types of products? Approximately how much is recycled?

2. Commit

Set an ambitious, public goal to reduce your company’s plastic footprint and report progress annually. Prioritize eliminating plastics that are rarely recycled, such as anything coded three or higher.

3. Innovate

Invest in and test new ways to deliver products that do not rely on single-use plastics, and prioritize reuse rather than throwaway packaging.

4. Educate

Let your customers know about your efforts to reduce your plastic footprint, and urge them to support these efforts by choosing products designed for reuse.

5. Advocate

Support public policy initiatives that will phase out single-use plastic items.

6. Collaborate

While some steps to move away from single-use plastics are clear, others are complicated and involve questions about the sustainability of alternative materials, such as carbon footprints, compostability, biodegradability, and water and land issues. Greenpeace can help work through these and other questions and encourages companies to consider additional organizations with expertise in this area.[x]

Everyone Must Take Action

Five Ways Grocery Retailers Must Lead

As fish stocks collapse, plastics choke our oceans, and workers continue to be at risk of labor and human rights abuses, retailers must use their purchasing power to bring about positive change for our oceans and seafood workers. Here are five ways they can lead:

1. Create a strong, time-bound, publicly available sustainable seafood policy

Retailers with guidelines covering all seafood categories are better able to ensure that they are not causing undue harm to the oceans throughout their operations. Avoid seafood connected to overfishing or destructive fishing and farming methods. In most cases, a rigorous policy can help retailers avoid being lured by the purported sustainability of eco-certifications or the promise that every FIP or AIP is actually improving the targeted fish stock or greater ecosystem.

2. Take action to stop forced labor, labor abuse, and IUU fishing

Retailers must improve traceability, transparency, and enforcement mechanisms to ensure that any seafood they source is free of labor and human rights abuses. This includes addressing problematic transshipment at sea, supporting legally binding agreements that protect workers’ rights, and calling on FCF and other companies linked to unsustainable or unethical practices to improve immediately.

3. Reduce your plastic footprint

Set an ambitious, public goal to reduce your company’s plastic footprint and report progress annually. Prioritize eliminating plastics that are rarely recycled, such as anything coded three or higher.

4. Support initiatives and advocate for positive change for our oceans and seafood workers

Retailers must advocate for policy makers to protect our oceans, improve fishery management, and protect seafood workers’ rights throughout the supply chain. Retailers can also encourage their customers and the public at large to pressure decision makers on these issues.

5. Increase transparency through data, chain of custody, and education

Responsible seafood is impossible to achieve without establishing strong traceability mechanisms. Traceability must cover the fishing vessel or farm to the point of sale, allowing customers to make educated choices based on all available information. Be transparent with your shoppers both on your website and in stores.

Five Ways Customers Can Take Action

As fish stocks collapse, plastics choke our oceans, and workers continue to be at risk of labor and human rights abuses, shoppers can vote with their dollar and let retailers know why they want healthy oceans and sustainable, ethical seafood. Here are five ways to demand change from major retailers:

1. Know the facts and speak your mind

Visit greenpeace.org/usa/carting-away-the-oceans to learn more. Bring some friends and talk to grocery store managers about seafood sustainability, ocean health, and workers’ rights.

2. Join the #BreakFreeFromPlastic movement

Sign up[xi] and demand that supermarkets announce ambitious, public goals to reduce their plastic footprints. Take pictures of ridiculously overpackaged items and post them on social media, and talk to store managers about reducing their plastic footprint.[xii]

3. Eat tuna? Make sure it is sustainable and ethical

Tell your supermarket that you want responsibly caught tuna, and express your concern if it is coming from suppliers that cannot guarantee sustainable and ethical products, like FCF, Bumble Bee, and StarKist.[65]

4. Vote with your dollar

Do not buy orange roughy, Chilean sea bass, or bigeye tuna. Use the Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch app[66] to buy only green rated “Best Choices” seafood. Ask how your supermarket is addressing concerns about forced labor, labor abuse, and illegal fishing. If you are not satisfied with its response, take your business elsewhere.

5. Eat less seafood

Today’s demand for seafood far outweighs what can be sustainably sourced. Reducing seafood consumption now can help lessen the pressure on our oceans, ensuring fish for the future.

Retailer Profiles

#1 Whole Foods Market

Headquarters: Austin, TX

Stores and Banners: 467 stores operating as Whole Foods Market and Whole Foods Market 365

Background: Whole Foods is known for its natural and organic products. Amazon’s acquisition of Whole Foods sent shockwaves throughout grocery retail.[xiii] Whole Foods has cut prices and has begun offering a series of perks, including discounts for Amazon Prime members. Its FY 2017 revenue was $14 billion.[67]

Greenpeace Comments: Whole Foods continues its reign as the top-ranked retailer in this assessment. From launching its new tuna policy to continued advocacy initiatives for improvements in fisheries management, Whole Foods is remaining active on sustainable seafood. Recent reports have scrutinized Whole Foods regarding its lack of public labor standards (see Struggling to Uphold Labor and Human Rights Standards). As labor and human rights abuses persist in the seafood industry, Whole Foods has the opportunity to lead with the same tenacity as it has on sustainable seafood.[xiv] The retailer must also take action to tackle plastic pollution. While time will tell whether its recent acquisition by Amazon will affect future seafood-related decisions, for now Whole Foods remains the leader in this assessment.

Sustainable Seafood Policy: Whole Foods’ seafood policy requires that it buy only seafood that is green or yellow rated according to Seafood Watch, or is in a time-bound FIP or AIP. The policy applies to its fresh/frozen seafood, shelf-stable tuna, and any prepared foods that use tuna. Its public canned tuna policy[68] is above and beyond that of any other retailer profiled. It is the only policy among profiled retailers that requires sourcing only one-by-one tuna (e.g., pole and line, handline, troll), and has traceability requirements that help ensure a sustainable and traceable product. A shopper interested in canned tuna can walk into any Whole Foods in the country, grab any brand of tuna on the shelf (private label or national brand), and be assured of its sustainability. This is no small feat.

Another unique element of Whole Foods is that it still relies on its own standards for farmed salmon, other finfish, and shrimp, instead of relying on incomplete third-party certifications. These standards raise the bar for aquaculture suppliers regarding environmental standards and animal welfare.

Seafood Sustainability Initiatives: Whole Foods conducts third-party audits to review its suppliers’ farmed fish, shrimp, and mollusc aquaculture operations. While it reviews IUU vessel lists to ensure it is not inadvertently sourcing illegally caught tuna, Whole Foods should also reference these lists for any wild-caught species that it procures. Whole Foods does not have a policy on transshipment at sea in the tuna industry, although because it does not source from purse seine or longline fleets, this is essentially not an issue for its sourcing. The retailer also signed on to a 2018 tuna RFMO advocacy letter[xv] calling for fishery management improvements.

Whole Foods has been moderately active in reducing plastic pollution. It requires a minimum amount of post-consumer recycled plastic in the packaging for some items it carries in stores, and is actively considering alternatives for some of its in-store items (like single-use plates). However, it must swiftly and markedly strengthen its initiatives as the plastic pollution crisis worsens. Especially given Amazon’s massive single-use plastic footprint, Whole Foods has an opportunity to set the bar for U.S. retail by developing a strong, comprehensive policy to phase out single-use plastics.

Labeling and Transparency: Whole Foods features prominent signage to inform customers about sustainable seafood choices and uses color-coded sustainability labels for each species in the wetcase. Through in-store flyers, brochures, and signage, the retailer communicates about various standards, including its own aquaculture standards. Whole Foods prioritizes transparency with its standards, publishing this information online and updating its customers and the public on its seafood sustainability milestones. Its private label tuna even carries a quick response (QR) code for consumers to use to learn more about the tuna’s sourcing. This approach could be used to share more data about other products, further increasing Whole Foods’ performance in this category.

Inventory: Despite its robust seafood standards, Whole Foods’ desire to carry a wide selection of species continues to affect its inventory score. For example, instead of refusing to carry Chilean sea bass, Whole Foods sells an MSC certified product. While Whole Foods is certainly not the only retailer to use this loophole, it is disappointing to see an industry leader in so many other areas continue to use this strategy with such a sensitive species. Whole Foods should also discontinue bigeye tuna.

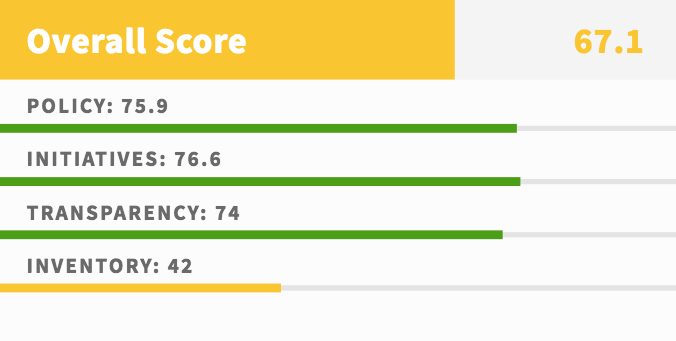

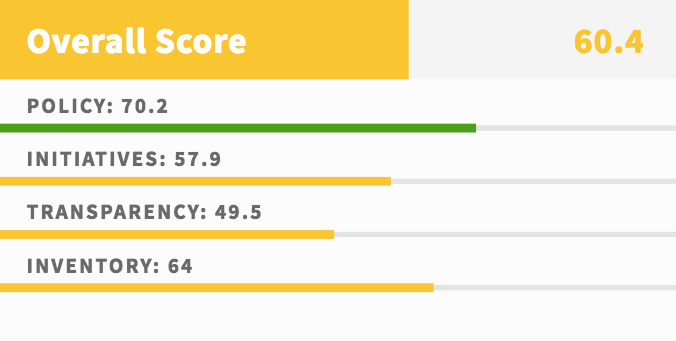

#2 Hy-Vee

Headquarters: West Des Moines, IA

Stores and Banners: 245 stores operating as Hy-Vee and Hy-Vee Drugstore

Background: Hy-Vee is an employee-owned company with stores located in the Midwest. Its FY 2017 revenue was $10 billion.

Greenpeace Comments: This Midwest retailer continues its rapid ascent in the rankings, and has moved ahead of Wegmans into second place. Hy-Vee was the category winner for the initiatives and the transparency categories. Hy-Vee has released a shelf-stable tuna policy, has finished converting all of its private label canned tuna to be sustainably sourced, and is investigating the concerns associated with transshipment at sea. Greenpeace encourages Hy-Vee to quickly complete its work to ensure, like Whole Foods, that all shelf-stable tuna sold in its stores is sustainable. Hy-Vee should build on its zero-waste initiatives to release strong public commitments and a policy to tackle single-use plastics, and join labor organizations like ILRF to support legally binding agreements for workers’ rights in the seafood industry.

Sustainable Seafood Policy: Hy-Vee’s seafood policy requires that it source only seafood that is green or yellow rated according to Seafood Watch, from a certified equivalent, or in a time-bound FIP or AIP. The policy encompasses its fresh and frozen seafood, shelf-stable, sushi, and deli categories. Since December 2017, Hy-Vee has sold only sustainable private label tuna (e.g., pole and line, FAD-free),[69] and is currently working with its NGO partner FishWise on plans to ensure that any national tuna brands sold in stores also meet its policy. Given the relative strength of its shelf-stable tuna policy, it is odd that Hy-Vee has a preferential sourcing requirement of ISSF participating companies, which would not ensure Hy-Vee receives sustainable, ethical shelf-stable tuna (see Tuna Improvements and Challenges). Hy-Vee should seek to emulate Whole Foods’ policy,[70] only source one-by-one caught tuna, and stick with its stronger policy standards that go beyond ISSF’s insufficient supplier requirements. While Hy-Vee appears to have extensive internal social standards, in contrast to some other top-five ranked retailers, Hy-Vee lacks a comprehensive public policy regarding labor and human rights.

Seafood Sustainability Initiatives: Hy-Vee conducts supply chain audits to determine whether its products are in compliance with its sustainability, traceability, and IUU fishing/social risk standards. The retailer relies on the combined Trygg Mat Tracking IUU vessel list[71] to identify whether the listed vessels are linked to its supply chains. Hy-Vee is currently considering its approach to addressing transshipment at sea in the tuna industry, and signed the 2018 tuna RFMO letter, building on years of calling for improved RFMO fisheries management. To further integrate its focus on ethical seafood procurement, Hy-Vee should support ILRF’s call to action for legally binding agreements that protect seafood workers’ rights (see Struggling to Uphold Labor and Human Rights Standards).

In conjunction with its distribution subsidiary Perishable Distributors of Iowa, Hy-Vee has focused on waste reduction, including plastics recycling and encouraging its customers to use reusable bags. Because recycling alone will not solve the global plastic pollution crisis, Greenpeace urges Hy-Vee to build on its sustainable seafood leadership and announce bold commitments to phase out single-use plastics in its operations.

Labeling and Transparency: Hy-Vee’s Seafoodies blog[72] educates its customers on sustainable seafood and even advises them which species to avoid (e.g., Chilean sea bass). On multiple industry conference panels, Hy-Vee representatives make a concerted effort to explain to others in the industry why sustainability makes business sense, and to urge action among their peers. In stores, its staff is trained to answer sustainability questions. Hy-Vee places a “Responsible Choice” label on service cases, the frozen section, sushi bars, in-store restaurants, and the canned tuna aisle for products that are green or yellow rated by Seafood Watch or a certified equivalent. Hy-Vee can improve by providing additional traceability labeling at the point of sale, whether on the packaging itself, through signage, or in other displays.

Inventory: Greenpeace commends Hy-Vee for avoiding Chilean sea bass for sustainability reasons, and communicating this policy to its customers.[73] Other top-five retailers Whole Foods and Giant Eagle should take note of this leadership. According to its seafood policy, Hy-Vee works to mitigate concerns associated with its wild-caught and farmed sourcing, which it employs with Atlantic cod, for example. However, Hy-Vee’s reintroduction of Atlantic cod and the need to improve its pangasius sourcing precipitated a drop in its inventory score. As Hy-Vee works to improve the sustainability of national canned tuna brands sold in its stores, it should also ensure that any salmon and shrimp sold is green rated by Seafood Watch.

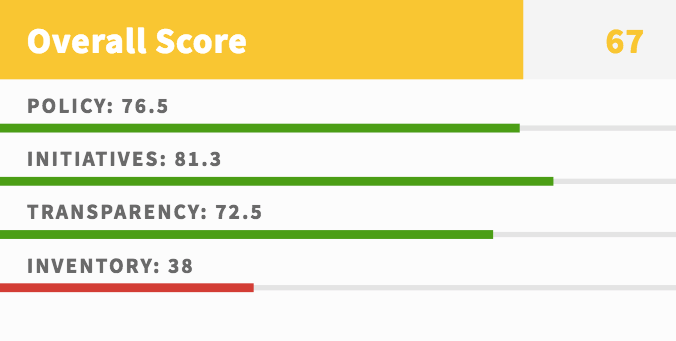

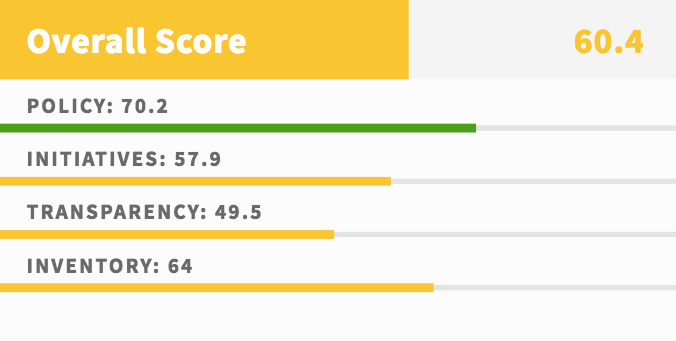

#3 ALDI

Headquarters: Batavia, IL

Stores and Banners: 1,695 stores operating as ALDI

Background: ALDI US (“ALDI”) is a rapidly expanding discount chain that sells mostly private label products, and is owned by German parent company ALDI Süd. Its FY 2017 revenue was $16.8 billion.

Greenpeace Comments: ALDI made enough progress this year to earn a spot in the green category. Greenpeace applauds the retailer for this first-time achievement. Since the last assessment, ALDI has been busy: it released a comprehensive shelf-stable tuna policy, launched a sustainable line of private label canned tuna, and has advocated for tuna fisheries management improvements. ALDI should continue to improve its tuna procurement, especially its longline caught albacore, as well as strengthen its farmed salmon and shrimp sourcing. Like every profiled retailer, ALDI needs a comprehensive policy to phase out single-use plastics and should build on its social compliance policies by joining ILRF’s call to action for legally binding agreements to protect seafood workers’ rights.

Sustainable Seafood Policy: ALDI has a public policy that covers its seafood storewide. It consults FishSource to inform its sourcing, particularly for its wild-caught assortment, and it will only source from FIPs that achieve an A, B, or C rating as assessed by SFP. ALDI may preferentially source MSC or Best Aquaculture Practices (BAP) certified products, and for shelf-stable tuna, its policy requires preferential sourcing of pole and line or FAD-free tuna. While ALDI also preferentially sources albacore from mitigated longlines (e.g., circle hooks), this alone will not comprehensively guarantee sustainability, as noted in an SFP guide on longline bycatch mitigation.[74] And given concerns with transshipment at sea, ALDI would fare better to switch to pole and line tuna altogether (see Tuna Improvements and Challenges). ALDI could benefit from strengthening its policy so that it sells only sustainably caught tuna storewide, which should be easier to accomplish because it does not sell any national tuna brands. Such a move would put ALDI shoulder to shoulder with Whole Foods on selling only sustainable canned tuna; no shopper could mistakenly purchase a can of destructively caught tuna.

Seafood Sustainability Initiatives: ALDI was among the first U.S. retailers to release a public shelf-stable tuna policy. ALDI permits transshipment at sea only with 100% observer coverage, and signed the 2018 tuna RFMO letter. Greenpeace commends ALDI on its social standards, which are publicly available and more robust than those of most retailers. As a signatory of the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh,[75] this suggests that ALDI recognizes the value of legally binding agreements between businesses, NGOs, and labor unions to improve workers’ safety and rights. Given that social certifications and initiatives like the Seafood Task Force alone will not create the transformation needed, Greenpeace urges ALDI to build on its work in the textile industry and join ILRF’s call to action for legally binding agreements in the seafood industry (see Struggling to Uphold Labor and Human Rights Standards).

ALDI appears to be in the early stages of developing a larger strategy to address single-use plastics, which is encouraging because U.S. retailers need to quickly address the plastics crisis. Especially given its business model focused on private label products, ALDI has the potential to markedly reduce its reliance on single-use plastics and set the bar for other retailers to follow.

Labeling and Transparency: ALDI leads among profiled retailers regarding on-package labeling of seafood products: it communicates to customers the species’ scientific name, catch or production method, and Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) catch area (if applicable). ALDI should publish this information on its website or elsewhere online. For example, other retailers like Publix, Walmart, and Giant Eagle have opted to provide some of their wild-caught sourcing data online via ODP. ALDI could go further by also disclosing its farmed sourcing data, and ensuring data for all of its seafood sold in stores are available through this resource.

Inventory: ALDI is among the top performers in this category, in part because it carries a limited variety of seafood. It also tends to source certified products, which can sometimes help mitigate issues associated with species like shrimp and farmed salmon. However, no certification fully addresses the environmental issues associated with these. Furthermore, most popular certification schemes ignore or ineffectively address serious labor and human rights concerns in seafood supply chains (see “Certified” Sourcing and Troubling Policy Developments). ALDI sells both pole and line and FAD-free skipjack tuna, and its yellowfin tuna is either handline caught or FAD-free. ALDI needs to improve its albacore tuna sourcing immediately.

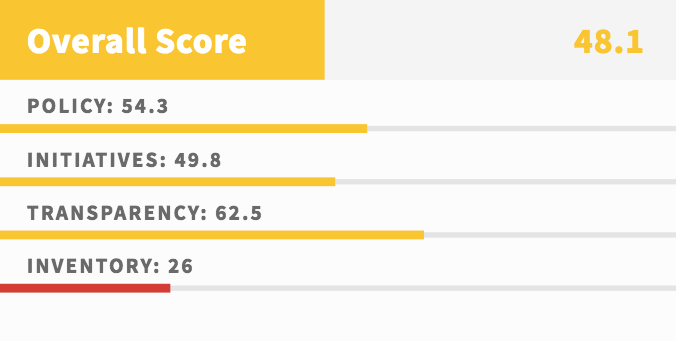

#4 Target

Headquarters: Minneapolis, MN

Stores and Banners: 1,834 stores operating as Target, CityTarget, and TargetExpress

Background: Target continues to invest in its grocery division, acquiring Shipt to better compete in online grocery delivery as it spends $1 billion to modernize stores. Its FY 2017 revenue (for consumables) was approximately $30.9 billion.

Greenpeace Comments: Since 2010, Target had one constant source of pride: unlike every other profiled retailer, it never buckled under industry pressure to sell farmed salmon, instead carrying only sustainably caught wild salmon. Until now. Since the last survey Target has quietly begun selling farmed salmon once again. Industrial-farmed salmon is a dirty business,[76],[77] and unfortunately Target is once again a customer. Due to improvements in other areas, Target’s overall score improved slightly from the last assessment, enough to push it from 5th place to 4th place. To remain in the top five, Target has to improve its seafood procurement, tackle plastic pollution, and ensure workers’ rights throughout its supply chains.

Sustainable Seafood Policy: In November 2017, Target expanded its publicly available sustainable seafood policy to include shelf-stable tuna and sushi. Target is working with its NGO partner FishWise to develop a strategy and timeline to transition its unsustainable shelf-stable tuna products to sources that meet its policy. The retailer requires that its seafood be green or yellow rated according to Seafood Watch, from a certified equivalent, or in a “credible, ‘time-bound improvement process.’”[78] All of Target’s farmed seafood is either BAP or Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC) certified. Despite Target’s public commitment to not sell GE seafood, it is unclear whether this policy applies only to its private label Simply Balanced products, or also to national brands.

Seafood Sustainability Initiatives: Target relies on internal and external audits to assess its supply chain, and is involved in various industry-led fora to address seafood traceability and human rights abuses in the seafood industry,[xvi] though doubts remain as to the effectiveness of these bodies. To help make transformative changes in the global seafood industry, Target should embrace ILRF’s call to action for legally binding agreements to protect seafood workers’ rights (see Struggling to Uphold Labor and Human Rights Standards). Target is currently investigating the issues associated with transshipment at sea in the tuna industry. Greenpeace urges Target to require strong supplier standards if it opts to continue sourcing transshipped tuna, and not to outsource its position to insufficient standards such as ISSF (see Tuna Improvements and Challenges). Target has joined a growing number of businesses and NGOs calling on tuna RFMOs to improve their fisheries management.

Target has a guideline to avoid using polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and is working to eliminate polystyrene packaging in its own brands. The retailer must significantly ramp up its efforts to phase out single-use-plastic packaging to more effectively mitigate its role in the global plastics crisis.

Labeling and Transparency: Target has improved in this category since the last assessment, though it is not fully on par with its higher scores in the other categories. Target has finally devoted some on-package labeling and in-store signage to sustainability messaging. As the retailer continues to focus on traceability and ethical supply chains, it should also make a point to communicate to the public updates regarding these initiatives, like it does on its progress toward compliance with its seafood policy.

Inventory: Target dropped in this category following the last assessment, reflecting its regrettable decision to reintroduce farmed salmon. Target should discontinue farmed salmon, and stick with wild-caught salmon. Fortunately, the company does not sell red list species such as orange roughy or Chilean sea bass. As some retailers succumb to reintroducing these species with the promise of “certified sustainable,” Greenpeace urges Target to keep these species off its shelves. Target should improve its farmed shrimp procurement and ensure all tuna sold in its stores, even national brands, is sustainably sourced.

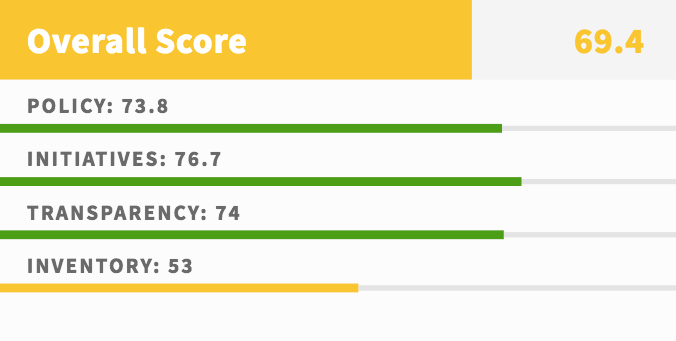

#5 Giant Eagle

Headquarters: Pittsburgh, PA

Stores and Banners: 412 stores operating as Giant Eagle, Giant Eagle Express, Market District, Market District Express, and GetGo

Background: Giant Eagle is a privately owned, regional retailer, with its largest presence in Pennsylvania and Ohio. Its FY 2017 revenue was $8.9 billion.

Greenpeace Comments: Giant Eagle was the dark horse of this year’s rankings, climbing six spots to round out the top five—an impressive feat for a retailer that was ranked 16th just a few years ago. After being the first U.S. retailer to release a shelf-stable tuna policy, it introduced a pole and line private label canned albacore product. Now, Giant Eagle needs to convert the rest of its shelf-stable category (private label and national brands) to sustainable sourcing. The retailer advocates for better fisheries management and has increased its transparency, from sharing its policies to publishing some of its sourcing data online. Greenpeace commends Giant Eagle for its year-over-year improvements, and urges the retailer to join the rest of the top-five retailers by discontinuing orange roughy and most[xvii] top-five retailers by discontinuing Chilean sea bass. Both are long-lived, slow-growing species that—based on sustainability and/or IUU fishing concerns—should not be commercially available, regardless of MSC certification.

Sustainable Seafood Policy: Giant Eagle primarily relies on the FishSource database to inform its procurement, and sources from a variety of FIPs, most of which are performing well. While the retailer has basic wild-caught standards, they could be strengthened with regard to how it ensures supplier compliance. Giant Eagle’s farmed seafood standards could be interpreted as “carry as much BAP certified product as possible” based upon its actual inventory, but this could also be clarified. Virtually all of its inventory is BAP 2-star certified, and for farmed salmon, tilapia, and private label shrimp, Giant Eagle carries up to 4-star certification. Its canned tuna policy requires 100% observer coverage and has a goal to avoid sourcing from longline vessels that transship at sea.

Seafood Sustainability Initiatives: Giant Eagle takes a proactive approach to ensure that its suppliers are well versed in seafood sustainability and that they understand the company’s expectations. Surprisingly, the retailer lacks a social responsibility code of conduct, and must address this oversight immediately. Especially given rampant labor and human rights abuses in the industry, relying on third-party certifications is inadequate; instead, leading retailers should support legally binding agreements that protect workers’ rights (see Struggling to Uphold Labor and Human Rights Standards). Giant Eagle added its support for improved fisheries management by signing the 2018 tuna RFMO letter.

While Giant Eagle has taken steps to reduce the amount of plastic bags used in stores, it does not have a comprehensive single-use plastic reduction policy or commitments to address its contribution to the global plastics crisis. This should be of utmost priority as Giant Eagle moves forward in its responsible seafood program.

Labeling and Transparency: Giant Eagle has made some data on its wild-caught sourcing available online via ODP. While encouraging, it must ensure that all data on seafood it sources, including farmed, are also available through this transparency initiative. The retailer has also increased its in-store labeling for customers, and has released a video detailing its commitment to sustainable seafood. Giant Eagle should continue to update its customers and the public on its efforts to improve on seafood sustainability and social responsibility.

Inventory: This is Giant Eagle’s weakest category. Similar to some other retailers, it over-relies on eco-certifications. Simply because a fishery is MSC certified does not necessarily mean it is ethical or sustainable (see “Certified” Sourcing and Troubling Policy Developments). To continue to remain in the top five, Giant Eagle should immediately discontinue sales of orange roughy and Chilean sea bass. Greenpeace commends Giant Eagle for dropping tongol tuna because of sustainability concerns and poor management, and urges the retailer to use this momentum to improve its skipjack tuna sourcing, and ensure that the rest of its private label and national brand shelf-stable tuna is sustainable (e.g., pole and line). Giant Eagle’s farmed seafood is probably its most stringent sourcing. However, industrially farmed salmon and farmed shrimp—however mitigated—are still associated with a host of environmental and social problems.

#6 Wegmans

Headquarters: Rochester, NY

Stores and Banners: 97 stores operating as Wegmans

Background: Wegmans is a regional, family-owned and -operated retailer based in the U.S. Northeast, and has a growing presence in Virginia. Its FY 2017 revenue was $8.7 billion.

Greenpeace Comments: Three short years after it was on the heels of Whole Foods for the number-one ranking, and following the departure of a veteran sustainable seafood champion, Wegmans’ ranking dropped from an industry leader to a modest performer. Wegmans’ jaw-dropping decision to procure both orange roughy and farmed Pacific bluefin tuna (for special events) has made it the only previously green rated retailer to either introduce or reintroduce such top-priority red list species. Greenpeace is concerned about these developments, and urges Wegmans to heed the warnings from many other NGOs and scientists regarding species like orange roughy and bluefin tuna, as well as maintain its focus on sustainable seafood.

Sustainable Seafood Policy: Wegmans’ sustainable seafood policy covers fresh and frozen seafood, and shelf-stable tuna. While it relies on SFP for advice, Wegmans simply requires MSC certification, a FIP, or the seafood to be caught in domestic waters. Its standards for farmed products could use clarification. Wegmans boasts 100% traceability, but works with the Global Aquaculture Alliance and ASC “when appropriate”[79] —indeed, much of its supply is derived from these certified sources. To its credit, Wegmans lists best practices for farmed salmon, but does not specify if these practices are required of suppliers. While Wegmans suggests that it will not sell GE salmon (or seafood),[80] it should commit to doing so and state this in its public seafood policy, especially since GE salmon is now available on the market.[81]

Seafood Sustainability Initiatives: Wegmans relies on SFP and Trace Register to determine whether wild-caught seafood is coming from legal sources. The retailer indicates it has 100% traceability for all of its farmed seafood. While Wegmans has a social code of conduct, it is unclear what standards are included in its internal policy. Wegmans should make this policy public and work with respected labor and human rights organizations to ensure its standards and grievance mechanisms are satisfactory. Furthermore, it should support legally binding agreements to protect seafood workers’ rights (see Struggling to Uphold Labor and Human Rights Standards). Wegmans is active in the public policy arena, from supporting marine reserves to stopping IUU fishing, and most recently signing the 2018 tuna RFMO letter urging improved fisheries management.

Wegmans has partnered with a private-sector company and a research entity to test packaging innovations that either substantially reduce the amount of virgin plastic used or replace it entirely with plant-derived substances. Greenpeace commends Wegmans on its initiatives and, especially because recycling cannot fix this problem (see Plastics Are Devastating Our Oceans), urges Wegmans to announce ambitious commitments to phase out single-use plastics altogether.

Labeling and Transparency: The updated Wegmans website removed some seafood traceability information that was available years ago (e.g., species-by-species pictures and geographical sourcing information). However, to its credit, its rebranded site still features a substantial amount of policy information and specific eco-certifications for farmed seafood products.

Earlier in 2018, Wegmans partnered with the National Aquarium to promote responsible aquaculture via an in-store pilot program in the seafood department called “Seafood Smart.”[xviii] The retailer has communicated to its customers information about its private label pole and line shelf-stable tuna through direct mail, signs at the point of sale, product demos, and at its pharmacy counters. Greenpeace hopes that Wegmans applies this same level of energy to other items in its wild-caught inventory, and ensures that the Seafood Smart program does not inadvertently steer customers toward some of the less responsibly farmed products that it currently sells.

Inventory: Wegmans dropped significantly in this category with its introduction of orange roughy and farmed Pacific bluefin tuna (the latter only available at special events). In general, Greenpeace acknowledges retailers’ efforts to use their buying power to make improvements (e.g., FIPs/AIPs). And even though this may be Wegmans’ intent, it is highly problematic, as orange roughy and Pacific bluefin tuna (both wild and farmed stocks[xix]) are so imperiled that they should not be commercially available, regardless of any certifications or attempts at improvements. Wegmans must get back on track and discontinue these species immediately.

#7 Albertsons Companies

Headquarters: Boise, ID

Stores and Banners: More than 2,300 stores operating as Albertsons, Safeway, Vons, Jewel-Osco, Shaw’s, Acme, Tom Thumb, Randalls, United Supermarkets, Pavilions, Star Market, Carrs, and Haggen

Background: This is the first assessment that profiles Albertsons and Safeway together, both operating as banners of Albertsons Companies (“Albertsons”), now one of the largest grocery retailers in the United States. Albertsons is expanding its online grocery delivery capabilities with Instacart and owns meal-kit company Plated. Its FY 2017 revenue was approximately $60.2 billion.

Greenpeace Comments: After years of inaction, Albertsons is making a concerted effort to tackle seafood sustainability, and has recently partnered with FishWise and Trace Register to ensure that 94% of its seafood will be green or yellow rated according to Seafood Watch (or be in a measurable, time-bound FIP or AIP) by 2022.[82] While Albertsons did not achieve a green ranking, which its former competitor (and now subsidiary) Safeway held, it performed well, with strong scores in three out of four ranking criteria. However, Albertsons outright failed the inventory category, clearly indicating where it needs to most improve. Especially given the size of its footprint, the faster Albertsons can reach its 2022 goals, the better.

Sustainable Seafood Policy: Albertsons is actively implementing improvements to ensure by 2022 that all of its seafood is Seafood Watch green or yellow rated, from a certified equivalent, or in a time-bound and measurable FIP or AIP. This policy applies to all of its fresh, frozen, and shelf-stable seafood, including sushi made in its prepared foods department. The retailer has also publicly stated that it will not carry GE salmon.[83] Greenpeace applauds Albertsons for making good on its policy commitment to discontinue eel, given the endangered status of wild-caught freshwater eel, the environmental impacts of farmed eel, and the illegal activity associated with the eel trade. Albertsons not only took action, it also began with a public commitment and then followed with additional press when it had discontinued eel, communicating why action is necessary.[84] Other retailers should follow Albertsons’ lead by discontinuing eel, and Albertsons should continue with this level of ambition as it implements its broader seafood policy.

Seafood Sustainability Initiatives: Albertsons usually conducts external audits annually, now works with Trace Register to conduct internal inventory audits in real time, and is establishing protocols to monitor IUU vessel lists. Greenpeace commends Albertsons for beginning to ask tough questions of its tuna suppliers, including identifying how to address transshipment at sea within its supply chains. Albertsons has supplier standards for labor and human rights, and as a member of the Seafood Task Force, it must adhere to its code of conduct. However, it must go further by supporting legally binding agreements to protect workers’ rights (see Struggling to Uphold Labor and Human Rights Standards). The retailer is well engaged in the policy arena, including publicly supporting improved tuna fisheries management.

Albertsons has also discontinued Styrofoam trays in some markets, has reduced the volume of plastics used in milk jugs and water bottles, has encouraged industry to use plant-based meat trays instead of polystyrene, and is actively seeking advocacy and innovation opportunities to realize additional reductions. Albertsons should build on this work by announcing a public commitment and timeline to phase out its reliance on single-use plastics.

Labeling and Transparency: Albertsons works with several external partners to improve its operations, promote its sustainability initiatives, and educate the public through a variety of online methods. Similar to other FishWise-partnered retailers, Albertsons has increased its media coverage of its various initiatives, from progress updates on its sustainable seafood program, to when it joined the Seafood Task Force, and most recently to when it discontinued eel. Other retailers should take note; this is how to keep customers, industry, and NGOs well informed about the case for sustainability and how to collectively work toward improvements. Albertsons’ in-store labeling for customers is a bit sparse and needs more attention. Greenpeace urges the retailer to make more traceability and sustainability information available at the point of sale.

Inventory: As one of the largest U.S. retailers, it is problematic that Albertsons performed poorly in this category. Fortunately, this should change as Albertsons discontinues red list species and implements its sustainable seafood policy. Albertsons should lead with the same principled approach that it did with eel, and immediately discontinue orange roughy, Chilean sea bass, and bigeye tuna. Additionally, it must rapidly transition to improved sourcing for most of its other high-volume products and continue to make improvements in its fresh, frozen, and shelf-stable tuna categories (i.e., only sell sustainable private label and national brand products).

#8 Sprouts Farmers Market

Headquarters: Phoenix, AZ

Stores and Banners: 300 stores operating as Sprouts Farmers Market

Background: Sprouts is a rapidly growing national retailer, with its highest concentration of stores in California and Texas. Its FY 2017 revenue was approximately $4.7 billion.

Greenpeace Comments: Sprouts’ 2018 debut in Carting Away the Oceans was strong, even scoring higher in the inventory category than most retailers, including Whole Foods. Sprouts is investing in staff education and online and in-store communications about its sustainable seafood initiatives—a great move that will better inform its customers about sustainable seafood. As Sprouts increases its market share, it also has an increased responsibility to leverage its brand and buying power for marked improvements in the seafood industry. Sprouts needs to publicly advocate for better fisheries management and for workers’ rights, and announce strong commitments to reduce single-use plastics in its operations.

Sustainable Seafood Policy: Sprouts recently released its seafood policy on its website. By 2020, Sprouts has a goal to source only from the following certified sources for all of its fresh, frozen, and self-stable seafood: BAP (3 star and higher), MSC, ASC, Alaska Responsible Fisheries Management, or Iceland Responsible Fisheries. Especially given concerns about reauthorization of the Magnuson-Stevens Act, it is imperative for Sprouts and other retailers relying on U.S. fisheries standards to advocate for strong, science-based protections. Currently, about two-thirds of Sprouts’ wild-caught seafood is MSC certified, and the remainder is either in a FIP or not certified. As Sprouts implements its policy, it must also consider the shortcomings of eco-certifications, which alone will not ensure sustainable seafood (see “Certified” Sourcing and Troubling Policy Developments). Two-thirds of its private label canned tuna is pole and line, with a goal of 100% by end of 2019. Sprouts will not purchase GE seafood, including GE salmon.

Seafood Sustainability Initiatives: Sprouts prohibits transshipment at sea unless there is 100% observer coverage. Sprouts conducts some third-party audits and has supplier agreements regarding legal and ethical procurement; however, given continued labor and human rights abuses in the seafood industry, it should strengthen its social standards and support initiatives like ILRF’s call for legally binding agreements (see Struggling to Uphold Labor and Human Rights Standards). It is unclear what Sprouts has done recently to advocate for improvements in fisheries management. With its new policy and public communications strategy, the retailer should use this momentum to advocate publicly for improvements, such as signing the 2018 tuna RFMO letter.[85]

Sprouts engages its private label suppliers on plastic packaging alternatives; it has a milk bottle take-back program in many stores to mitigate the need for single-use plastic milk jugs; and it is piloting the use of reusable and refillable containers for bulk honey, vinegar, and oil. To build on these initiatives, Sprouts could set the bar for U.S. retail with a comprehensive plan to reduce single-use plastics.

Labeling and Transparency: At the time of this writing, Sprouts has yet to robustly engage its customers either online or in stores about its sustainable seafood policy and products. Fortunately, Sprouts is focusing on a communications plan this year and also has plans to label certain products with sustainability information. As these initiatives roll out, Sprouts’ performance will improve in this category.

Inventory: Sprouts performed better than most retailers in this category. It does not carry several red list species for sustainability reasons, including orange roughy, Chilean sea bass, shark, and bigeye tuna. Greenpeace applauds Sprouts for this leadership and encourages it to stipulate in its seafood policy that it will not sell orange roughy, Chilean sea bass, and bigeye tuna in the future. The retailer is also making improvements in the shelf-stable tuna category and working to improve its swordfish procurement. Sprouts must improve its sourcing of Atlantic cod and grouper, among other species.

#9 Ahold Delhaize

Headquarters: Quincy, MA, and Salisbury, NC

Stores and Banners: 1,960 stores operating as Stop & Shop, Giant, Martin’s, Food Lion, and Hannaford

Background: In the previous assessment, Ahold and Delhaize were profiled separately. Following their 2016 merger, this is the first time that Ahold and Delhaize are profiled together. Ahold Delhaize USA continues to represent the largest share of the Dutch-owned global grocery giant’s portfolio. Its FY 2017 revenue was $42.3 billion.