The Paradox for Publishers and Authors

The First Amendment of the Constitution of the United States, the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights all are very clear about the freedoms that form the fundamental values of our society. These rights, including the freedom of speech and of the press, are the cornerstones of democracy because they guarantee an active exchange of ideas, open debate, the quest for solutions, and an informed public.

Authors, philosophers, journalists and other public figures have long been active agents fighting to protect these rights. Indeed, publishers themselves have been some of the most tenacious defenders against censorship. Penguin Books’ groundbreaking defense of Lady Chatterley’s Lover in 1960 [20] is just one example of a publisher at the forefront of an iconic free speech battle.

Industries and organizations that challenge political, economic or other forms of power are only able to do so because the freedom of speech has enshrined their right to exist. The book publishing industry and media companies, in particular, have long recognized the importance of freedom of speech to their existence and place in society. This is why the Association of American Publishers and almost a dozen other media organizations filed an amicus brief in 2016 in support of Greenpeace in the SLAPP brought by Resolute. They argued that free speech “is essential to ensuring a flourishing marketplace of ideas.” [21] And also, “publishers of all types rely on these broad protections to provide illuminating information to the public.” [22]

Publishers should also be acutely aware of the dangers of SLAPPs. In 2008, for example, Les Éditions Écosociété Inc. published Noir Canada, a critique of human rights and environmental violations by Canadian mining companies in Africa. One of the companies criticized in the book, Barrick Gold, responded by filing a CAD$6 million libel lawsuit against the publishers in Québec. In 2011, the Québec Superior Court concluded that Barrick Gold had intended to intimidate the defendants through its aggressive legal tactics. Nonetheless, the lawsuit was allowed to proceed and, to avoid the costs of a full trial, the publisher ended up settling out of court. Under the weight of the lawsuit, Les Éditions Écosociété was forced to stop further publication of the book. [23]

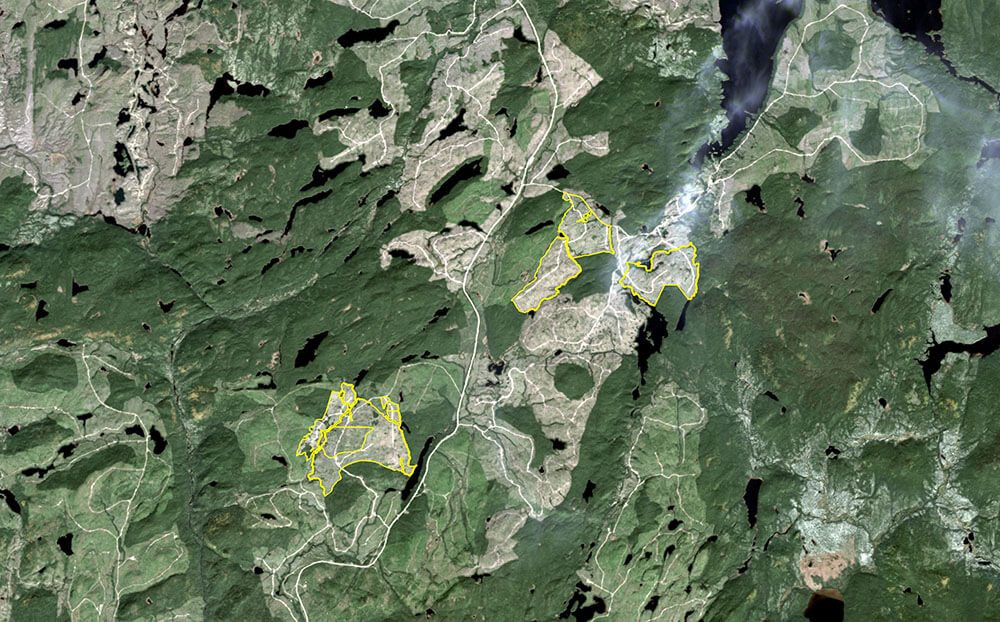

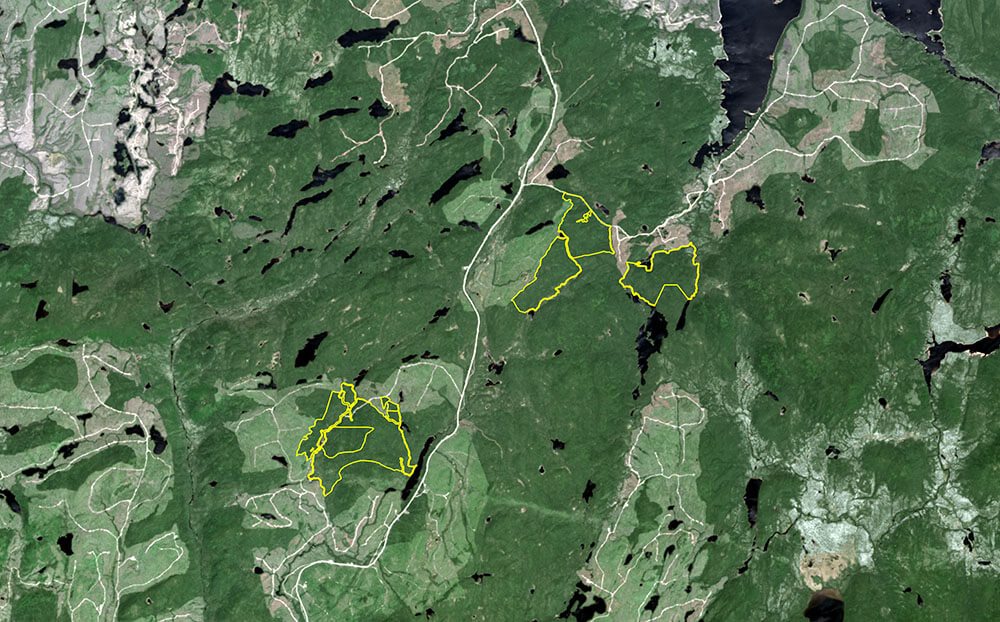

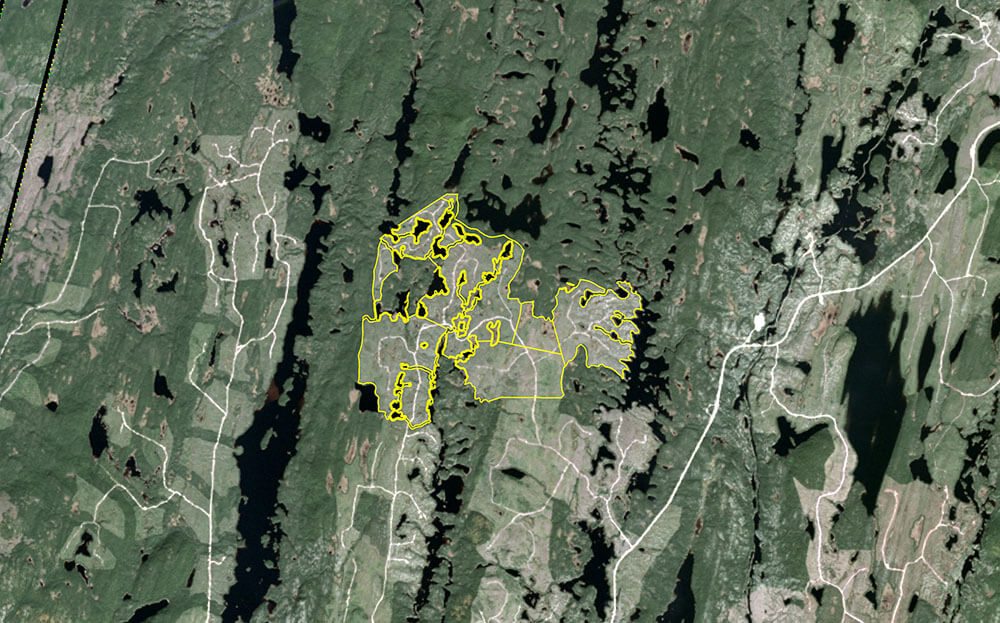

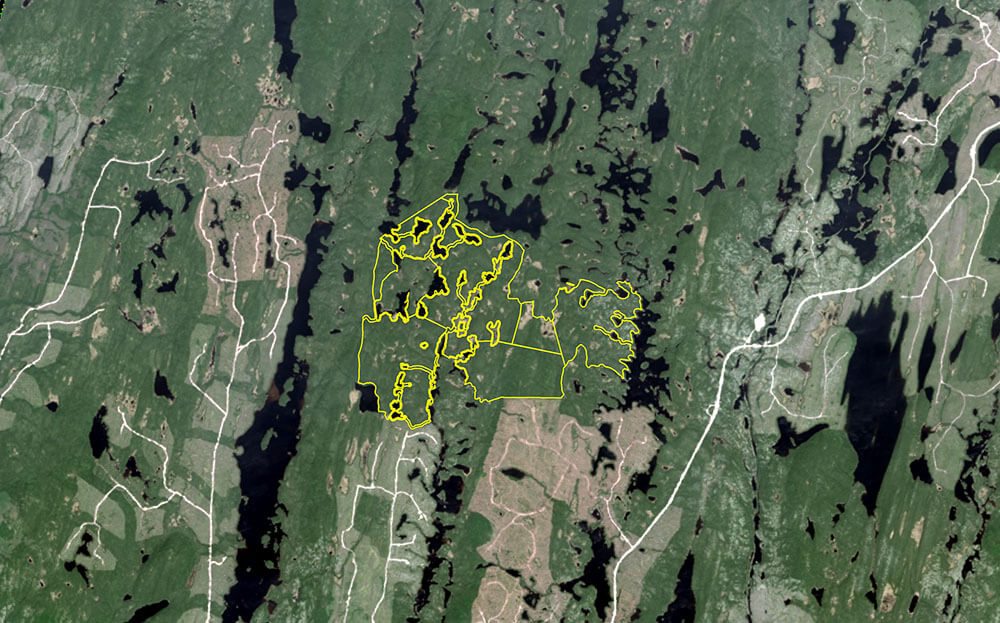

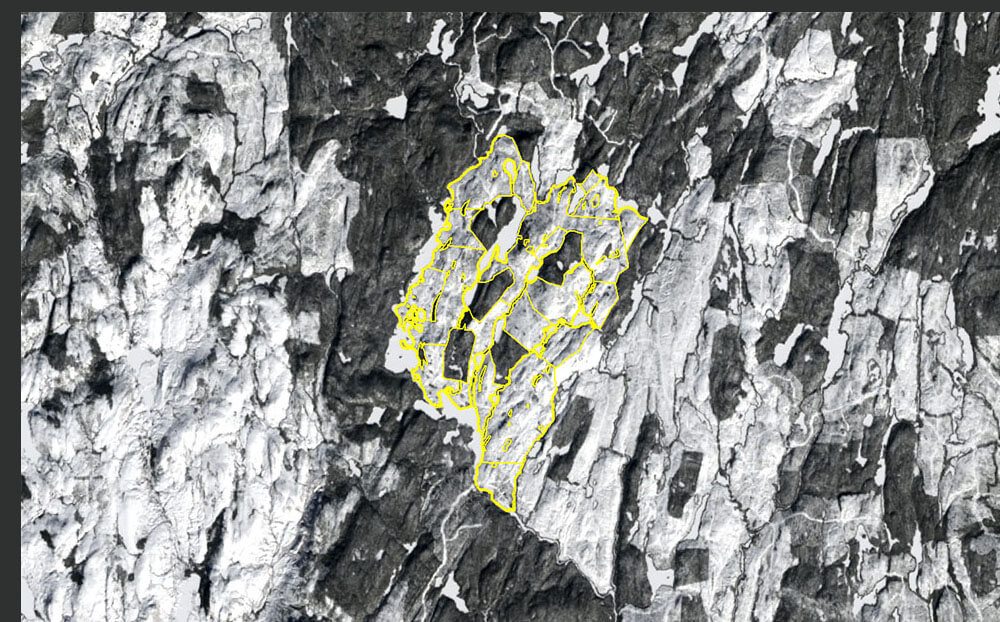

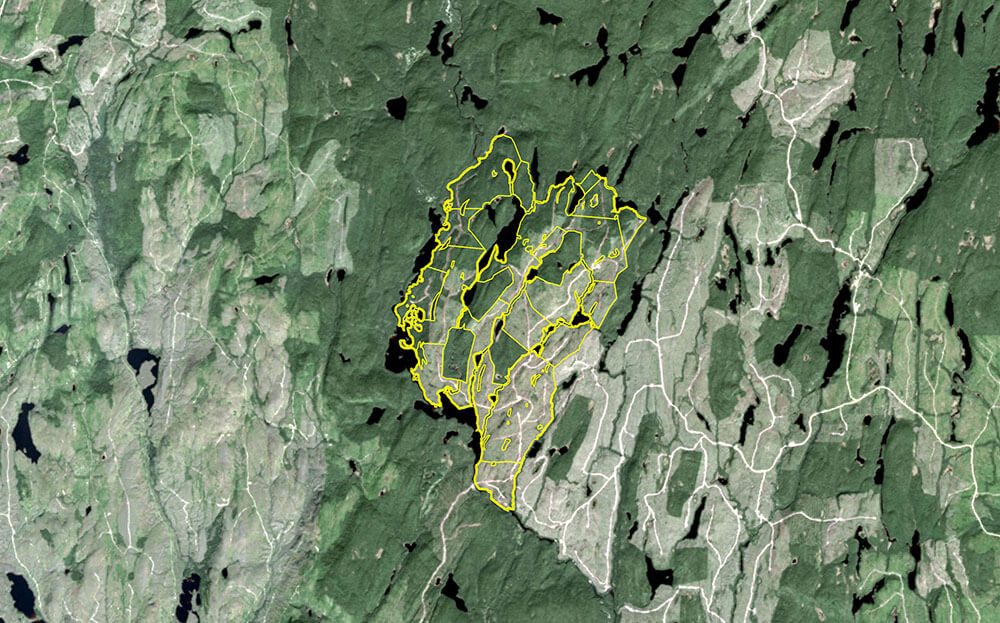

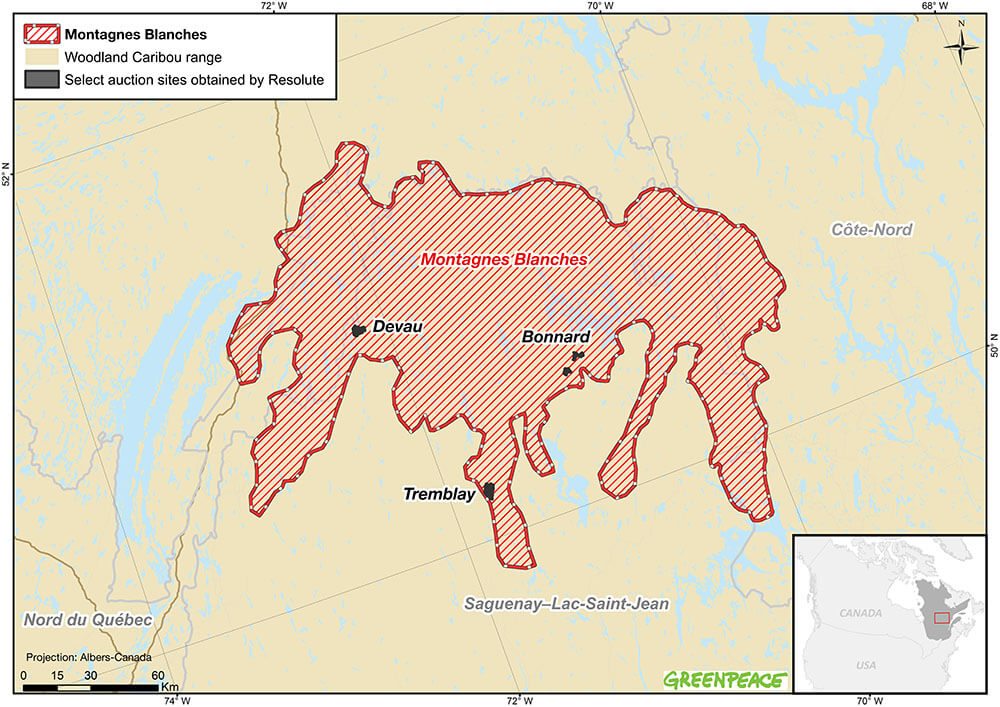

This then raises the question: why is almost every major global book publisher buying paper from the very company that is using this same tactic to threaten free speech? A Greenpeace investigation revealed that many of the world’s largest consumer books publishers, including Penguin Random House, HarperCollins, Simon & Schuster, and Hachette, among others, all buy and use book grade paper from Resolute, including from a paper mill in Canada’s boreal forest. Great strides have been made in recycled and sustainable production of paper, as well as heightened awareness of the forestry issues linked with paper production, and yet these publishers continue to buy paper from a controversial company linked to the destruction of intact ancient forests.

These large global book publishers are behind some of the world’s most beloved novels, children’s books and nonfiction works, producing millions of new titles and editions printed around the globe every year. [24] Doing so without supporting egregious attacks on free speech and without supporting the destruction of intact ancient forests and threatened species habitat is surely in their interest. The paradox of this situation, in which a supplier threatens the very freedoms that enable their customers to operate, is clear.

Each of these publishers has some form of global paper procurement standards or environmental policies already in place which, for one reason or another, should raise concern as to whether Resolute qualifies to be a supplier without first making sustainability reforms. [25] (See Table 1.) Companies should be diligent in examining the forestry practices of their paper suppliers on the ground, and in communicating expectations on matters of sustainable forestry to those suppliers. For these book publishers, it is not just about defending shared morals and protecting the rights fundamental to their own existence, but also about keeping the promises to their readers reflected in their policies.

If publishers fail to act to address these environmental and moral issues and instead wait for Resolute’s meritless lawsuits to be adjudicated, they help validate SLAPPs and embolden other corporations to pursue similar legal attacks against legitimate advocates speaking in the public interest. More fundamentally, such a position stands counter to the ethical standards of the entire publishing industry, including so many authors and readers around the world. Examining one’s supply chain, being committed to environmental policies and standing up for free speech is not simply a business decision that can wait, this is about corporate integrity and doing the right thing for the future we all strive for.