Farmworkers, like many other Black and Brown communities in this country, are practically sacrificed for the financial gain of major agricultural corporations.

Planeta G is back for Season 2 where we’re telling the real stories of powerful latinx/latine activists and farmworkers who are fighting for their communities.

In today’s episode, we are talking with two incredible farmworkers and organizers who are standing on the shoulders of giants and moving mountains. I found my way to working in the environmental movement through farmworker organizing, so I’ve always wanted to do a Planeta G episode that connected these issues.

During and after college, I focused my attention on US farmworkers and farmworker movements. My first two jobs brought me into all corners of this country to help farmworkers organize, protect themselves from harmful chemicals, and fight for fair wages. I saw the incredible struggles in places like Imokelee, Florida (where farmworkers created a successful campaign to fight for fair wages), and the Central Valley, California (also known as “America’s salad bowl”). Working with farmworkers made me realize I wanted to do more for the environmental movement. Seeing the cycle of climate fueled migration, abuse of workers rights in our capitalist economy, toxic exposure to contaminated water, fossil fuels, and industrialized agriculture, and the limited recourse so many of the workers had was devastating.

Farmworkers, like many other Black and Brown communities in this country, are practically sacrificed for the financial gain of major agricultural corporations.

Having all manner of fresh fruits and vegetables all times of the year for cheap? Let’s do it on the backs of farmworkers. Grow fruits and vegetables faster and easier? Sacrifice farmworkers and their families who are exposed to toxic chemicals, fertilizers, and pesticides. Work through extreme heat worsened by climate change, fires, and other extreme weather? Farmworkers do it to prevent losing their jobs and to feed their families.

We cannot live in a world where the lives of so many are put at risk for the financial gain of a few.

On this Planeta G episode, I talked to Lupe Marinez, who was born in Brownsville, Texas, and moved to California with his family in 1964 to start working in the fields of the San Joaquin Valley. While working in the grape fields in Ducor, Lupe met several organizers from the United Farm Workers, including César Chávez. He’s dedicated his life to working with the Union and the Center on Race, Poverty, and the Environment.

Si se puede, César Chávez, and what we can learn from a history of organizing

César Chávez was a labor leader and civil rights activist who together with Dolores Huerta co-founded the National Farm Workers Association, which later became the United Farm Workers labor union. The Union, through it’s powerful strikes and actions, changed the landscape for farmworkers, not just in California, but across the country. My first guest, Lupe Martinez, who worked for the union throughout his life (make sure you stick around for the clip after the credits where we meet Lupe’s amazing wife, Maria) reminded me Chávez was in fact one of the first environmentalists. When almost no one was talking about the toxic effects of pesticides and other chemicals on farmworkers and their families, the UFW made health and safety a central demand to protect workers. In 1970, after years of struggle, the Delano grape farmers and the UFW were up against signing a contract, not just for more fair wages, but also introducing a health plan with new safety measures regarding the use of pesticides. But, when this contract expired in the early 80s, Chavez started one of his most important protests, the table grapes boycott in McFarland, CA, then known as “cancer town,” because of its childhood cancer clusters caused by pesticides and fertilizers. The poisons came from drinking water tainted with the very chemicals used to grow the crops.

In 1988, outraged at the undue influence of the pesticide and fertilizer industries, he began a devastating hunger strike that lasted 36 days, drinking only water. The “Fast for Life,” which was supported by several celebrity activists, cost him 30 pounds and the weakening of his already frail body.

Together they were able to ban or restrict the use of some of the most lethal chemicals pesticides such as DDT.

Today, farmworkers are often still exposed to toxic chemicals, not just from pesticides and fertilizers, but also run off water from nearby oil extraction sites.

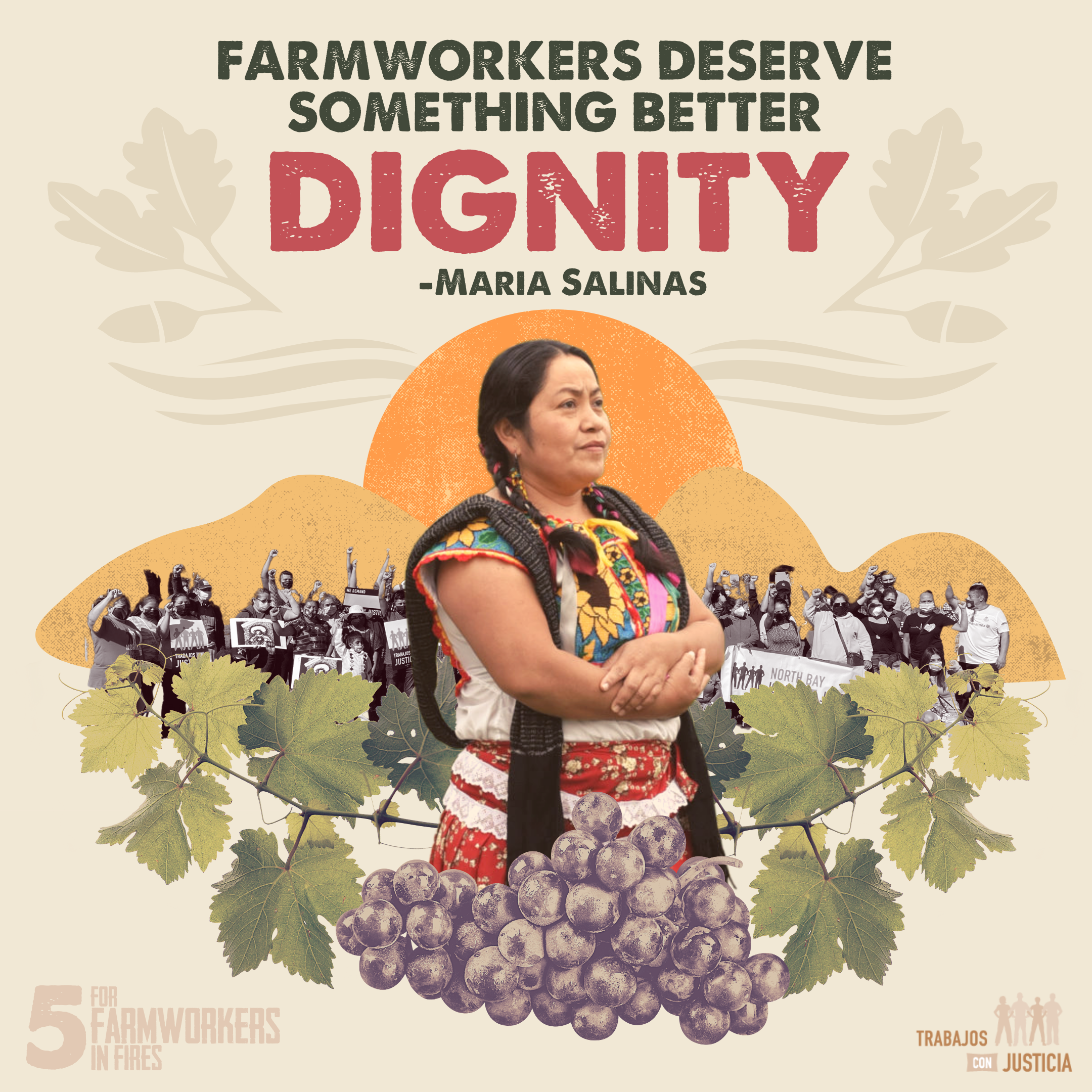

And the fight continues on! Later in the episode, I talk to Maria Salinas, a Chatina woman and farmworker who lives in Sonoma County, California and works in the grape fields. Maria is a leader in the Movimiento Cultural de la Unión Indígena campaign, where she organizes Indigenous meetups to celebrate dance, culture and food. She is originally from Cerro del Aire, Santo Reyes Nopala in Southern Oaxaca, and works with North Bay Jobs with Justice to fight for her community. She also provides interpretation between Chatina language and Spanish.

Sonoma county is on the forefront of the climate crisis. With increasingly intense wildfires, communities often face not just the dangers of the fires, but the suffocating smoke and ash. Farmworkers can lose their livelihoods if they don’t work, or risk their lives if they do. The region is known to many for their wine–and by organizing in this influential multi-million dollar industry, workers have been able to fight for a safer, more just work place.

5 for Farmworkers in Fires

With North Bay Jobs with Justice, Maria is fighting for 5 specific demands during fire season:

- Language Justice: All Safety and evacuation training for farmworkers should be held in the workers’ first language, including Indigenosu languages

- Disaster Insurance: Like growers, who often receive insurance pay when their crops are harmed due to disasters, farmworkers should continue to receive pay during wildfire season when they can’t work

- Community Safety and Observers: Community members are ready to volunteer to act as community safety observers and will be trained before harvest starts

- Premium Hazard Pay: Farmworkers deserve premium hazard pay when they are working in unhealthy and dangerous environments like evacuation zones, smokey air, near wildfires, and extreme heat

- Clean Bathrooms + Water: Increased numbers of workers during harvest combined with ash and soot from wildfires quickly dirties already crowded porta-potties. All farmworkers deserve clean bathrooms and water during harvest and wildfires

Watch episode 2 to learn more:

Missed episode 1? Or season 1? Check them out now! It’s not too late!

Si se puede! And don’t forget to tune in next Tuesday for the last episode in our second season of Planeta G.