In October and November 2023, a Greenpeace radiation survey team operated for three weeks in Ukraine. They visited the site of the world’s worst nuclear disaster at Chornobyl in northern Ukraine and traveled to the southern region near what could be the world’s next nuclear disaster at Zaporizhzhya. There, in cooperation with the Ukrainian NGO SaveDnipro, they deployed radiation sensors to monitor and provide early warnings in the event of a radioactive release.

Five members of the Greenpeace team took turns recording their experiences in a diary. They write about encounters with border control officers fascinated by their radiation measuring devices, the spooky streets of Kyiv under curfew, having lunch in the cantine of Chornobyl nuclear power plant or setting up sensors in the south of Ukraine. Throughout their time in Ukraine, they experienced numerous moving encounters with local residents, sharing stories of resilience, hope, and endurance. Through the eyes of the Greenpeace team, and the stories of those they encountered, the diary shares an insight into the challenges of environmental issues amidst the complexities of a country in crisis.

Sunday 29.10.2023 / Lublin

A sunny morning at the Lublin Bus Station. Mai from Japan, Anne from France, Jan from Belgium, Shaun from Scotland and I are drinking large cups of coffee – but that doesn’t help: We are tired before our trip begins, after weeks of preparations, first aid and hostile environment awareness trainings where we have learned how to apply a tourniquet and to tape heavy injuries.

Ukrainian border control takes a long time. The officers are fascinated by our 40kg heavy lead “quant”, an instrument like a super-sized salad bowl which measures radioactive samples. We keep opening our suitcase – click, click – and more and more officers are gathering, scratching their heads and discussing how to deal with it.

Suddenly, our driver gets angry: “My co-driver has disappeared”. He refuses to drive alone. “How can he have ‘disappeared’?” I’m asking. “He is not there anymore.” He answers. Then follows endless waiting. But at least we have cappuccino in Scottish tartan paper cups, pastries and ice cream. We were supposed to arrive in Kyiv at 10 pm, but seem to be trapped at the border checkpoint – with the next much bigger problem looming already: The war curfew in Kyiv, from midnight to 5am. We are getting worried. What if we don’t make it to Kyiv in time? We call our colleague Polina in Kyiv – she is a real troubleshooter. Bus station in Poland on the way from Hamburg to Kyiv.

Bus station in Poland on the way from Hamburg to Kyiv.

Monday 30.10.2023 / Kyiv

Suddenly, the co-driver reappears as mystically as he had disappeared, and some passengers whisper about “papers which were not in order”. We continue with a five hours delay. Our drivers go full speed through the Ukrainian night and its empty streets under a big endless sky with a full moon. Entering Kyiv at 3am is spooky. A gray and dark city. Soldiers with Kalashnikov’s at burning barrels and massive tank barriers block the roads. This is the end of our journey, but we’re still 20 km away from our hotel. A very young soldier is approaching us, but he is too shy to explain what he wants: Helping us? Cigarettes? I’m wondering if I should answer him in Russian because I don’t speak Ukrainian. After trying English, German and even French, I ask him in Russian – and he smiles. Better to understand Russian than to not understand at all.

And there, in the car passing by? Isn’t that Polina waving her hand? Yes, she has managed to pick us up. In front of her car is a police car. We can’t believe it: She has organized a special police escort to accompany us through the empty city to our hotel. What a welcome to Kyiv at 3:30 am.

Tuesday 31.10.2023 / Chornobyl / Jan Vande Putte

Today is our first day in the Chornobyl exclusion zone. We are departing from the hotel in Kyiv in the morning with cars fully loaded with equipment: material to protect us while working in the contaminated zone, and a series of measuring devices. Approaching Chornobyl, the area becomes less populated, the number of checkpoints increases, and the road becomes more damaged. To get into the exclusion zone, we need a special permission from the Ukrainian government. Apart from not only being a contaminated site following the 1986 nuclear disaster, the exclusion zone is also a military sensitive area today: We are close to the Belarussian border from where the Russian invasion towards Kyiv started on February 24th last year.

In Chornobyl, we meet with the director of the EcoCentre Serhii Kiriiev. He started to work in the zone in 1986 and is now leading the scientific work on the contamination in the area. 2600km2 – it’s not only vast in surface, but also immense in its complexity of contamination of water and soil. The Russian invasion has disrupted the management of this area, they looted and vandalized equipment, dug trenches into contaminated soil, and drove hundreds of tanks and heavy military vehicles through the zone. But they also set mines when they were pushed back by the Ukrainian army into Belarus. Since then, especially anti-personnel mines have become a huge problem because it makes access to the territory difficult and dangerous.

Serhiy Kireev, director of the “EcoCenter”, shows a locker damaged by Russian forces in the Chornobyl exclusion zone

Wednesday 1.11.2023 / Chornobyl / Jan Vande Putte

This morning, we are visiting the laboratories of the EcoCentre. Before the war, they were analyzing thousands of samples a year, but last year this was impossible. Now they are building up their capacity again. When we visited the laboratories in July last year, shortly after the Russian troops had left, the situation was dramatic, with vandalized labs, broken computers, and stolen equipment. They even had no printer. Over the last year, much has been re-established, but some damage to the machinery is very difficult to repair. Most interesting to us are the dirty rooms, where radioactive contaminated samples are incinerated or dried and further treated before they are analyzed. It is very exciting to see that such a world-class lab is following a very similar methodology as ours, but at a totally different scale.

Greenpeace expert Jan Vande Putte analyzes sediment samples from the cooling ponds with employees of the ‘EcoCentre’ in Chornobyl

Thursday 2.11.2023 / Chornobyl / Jan Vande Putte

Today we take samples in the cooling pond with Anton from the Ecocenter. As a result of the draining of the cooling pond since 2014, 75% of the original cooling pond is now most of the year dry. For someone who has taken hundreds of soil samples at contaminated places around the world, my brain switches and focuses on the technology and protocols. There are many processes at work in nature that have concentrated the contamination in deeper layers of the soil and into the waters far down: When we analyse a sediment in our own mobile laboratory, we observe a relatively very low contamination in the first 5 cm of the soil, while the highest contamination is seen in the 10-20 cm layer. Chornobyl is a place of extreme contradictions, overwhelming beauty and the largest nuclear disaster in history. Meanwhile I am looking at this place as a 3D model, trying to better understand all the complex processes…

Greenpeace and EcoCenter employees collect soil samples near the cooling ponds at the Chornobyl nuclear power plant

Friday 3.11.2023 / Chornobyl / Shaun Burnie

After several days of working at the cooling pond, the team’s last full day in Chornobyl starts with a visit to the memorial wall to the first victims of the 1986 disaster – the engineers and workers on duty the night of 26 April. The memorial wall stands opposite the entrance to the worker’s canteen, where we have been eating lunch the last few days. I was in the Soviet Union just after the Chornobyl disaster began in 1986, and have worked on nuclear issues for nearly 40 years. In all that time I had never expected to find myself eating delicious borscht sitting next to plant workers at Chornobyl. It is overwhelming to be here and such a surreal moment, as Susanne Vega and the hip hop version of Tom’s Diner is playing on the canteen sound system. When observing the workers, I am thinking: In addition to the 26th of April in 1986, a new date is now engraved in their memories: February 24, 2022 – the first day of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, when Russian armed forces attacked and occupied the Chornobyl plant on their way to Kyiv. Before, there were thousands of workers, today there are hundreds, and it’s not possible to continue as normal. I feel the deepest respect for these people.

We then visit nearby Pripiat, where nearly 50,000 people were evacuated on April 27, 1986, due to high radiation levels spewing from the burning unit 4 reactor. Standing in the middle of Pripiat it seems like the perfect moment to send a message to the Russian nuclear industry and the Russian State Nuclear Corporation, Rosatom. From day one of the 2022 occupation, Rosatom personnel were on the Chornobyl site with their military. Standing with our banner in Pripiat, we make clear that Rosatom – because of its direct role in the Russian war against Ukraine – must be punished through sanctions to stop its nuclear business overseas.

Protest is the ghost town of Pripyat: We demand sanctions against the Russian company Rosatom because of its role in the war

Saturday 4.11.2023 / Chornobyl / Tobias Muenchmeyer

I got up very early to pack my stuff, ready to leave Chornobyl after four intense days. Time for a walk before breakfast. I don’t know why I chose a Chopin piano concert to put on my ears but suddenly everything I see gets blurred. I’m walking through the cold and cloudy morning air, the city is still asleep. A limping dog approaches me, sniffing at my backpack. I would like to say hello, but I got clear instructions: “Avoid touching anything in the Chornobyl zone. Just imagine that everything you see has been freshly painted, and your main task is to come home clean, without any color spots!” So I walk away, with the eyes of this dog haunting me.

I walk down “Soviet Street”. A large label on a house says “Ticket Office”. The glass is broken and branches of bushes loom out of the windows. So tickets for what? For 37 years no ticket has been sold here. The only ticket you can get in Chornobyl is the one to enter the inner 10 kilometer zone around the exploded reactor Number Four. Not here, but at the 30 kilometer zone checkpoint. It really is time to leave.. I’m tired of all of the mine warning signs, radiation measurement points, men with kalashnikovs at checkpoints, tanks, mock tanks and this whole jungle of memorials. The memorials, which almost nobody can access, are expressions of the helplessness and loneliness of the survivors of various catastrophes that took place in this deceptively beautiful and seemingly innocent cosmos.

Sunday 5.11.2023 / Kyiv / Tobias Muenchmeyer

Returning from Chornobyl you feel dirty. “Get clean again!” rings in my head. Back in Kyiv I took a hot shower, then a bath, gave all my clothes to the laundry and slept for a long time. Breakfast in clean clothes with normal hotel guests without camouflage, fresh coffee, porridge with honey, bliny, croissants – back to life!

After breakfast I enjoy a walk in the city center. I turn around the Bessarabskiy Market towards Khreshchatyk, the Champs Elysées of Kyiv. Young people enjoying a Sunday late morning stroll, small groups, young couples. I’m walking under the iconic chestnut trees which are paving the pathway with their golden leaves, and passing Vitaliy Klichko’s town hall. This is exactly where I lived in 1995 and 1996 and every spot is charged with memories for me.

Later, I meet Denys in a cefé, a hydrologist from Kyiv who has a laboratory in Chornobyl. I’m asking him about the time when Chornobyl was occupied by the Russian Army. He says: “It was weird, they messed up my office, but when I cleaned it up, I realized that no hard drive, no documents, no scientific book was missing. The only thing which they took away was – my favorite book: the autobiography of Keith Richards”. He adds with a bitter smile: “You must know: I’m a big Stones fan.” And I wonder where this book is now, if he’s still alive, if he had believed what Russian propaganda had told him, or if he had protested against Putin in a time when that was actually possible.

Selfie by the Greenpeace team in the hotel in Kyiv

Monday 6.11.2023 / On the road, Dnipro / Shaun Burnie

Leaving Kyiv we head south-east following the river Dnipro. We have said our goodbyes to radiation specialist Mai from Japan and we have been joined by Christian, our videographer and photographer – we first worked together more than 20 years ago and together with Mai and Jan we have worked many years in the contaminated zones of Fukushima prefecture in Japan.

In between conversations and staring at a computer screen, I am taking the opportunity to view through the window. What I see makes it real what until now I have only read about: The seemingly endless flat fields of black, very black, soil. The winter sun is low and it’s hard at first to make out the dying stalks of last summer’s sunflower crop rooted in the black soil which is some of the richest in the world. The most amazing and productive soil – or Chernozem – was not able to save the millions of Ukrainian people who were killed by the famine of 1931 until 1934. Back then, the Holomodor was the consequence of Soviet politicians that were unable to acknowledge their devastating policies. All travel, everywhere, you are moving through history, but in Ukraine you feel it more than anywhere I have ever been.

Tuesday 7.11.2023 / Zaporizhzhia / Polina Kolodiazhna

We are on our way to Zaporizhzhya to install sensors at the local hospital. Before going, I was a little nervous about this trip because of the danger that may await us there. We move fast and safely on the road, so we make it in time for our first meeting with the deputy head of Military administration of the region. Next we head to meet the Head of the city council – a very brave young woman named Olena. She doesn’t have a proper office because she is forced to change her location all the time for security reasons. Her words and storys about resistance made me feel very moved.

We are taking a drive through the city. I used to think that Zaporizhzhya is an industrial city with polluted air, but instead it is beautiful – with wide streets and ancient buildings. It is difficult for me to see the consequences of the Russian war here Zaporizhzhya – destroyed buildings, damaged infrastructure and a very low level of water in the river after the Kakhovka dam was destroyed. And then for the first time in my life I am visiting the island Hortitsa – a very special place, full of energy, where the Ukrainian warriors Kozaki lived centuries ago. I wanted to go there before the full scale invasion, but never found the time. What an irony – now I am seeing Hortitsa during air alarms.

In the evening I am spending a lot of time thinking about all I saw today and before in other regions. All this damaged lives, destroyed childhoods and dreams. How can I help? How can I make changes and where to find strengths to support everyone who suffers? They say, the road will be mastered by the walking one. And this is what I keep saying to myself to move forward.

Greenpeace and SaveDnipro meeting with Ms. Olena Zhuk, the district chairwoman of Zaporizhzhia

Wednesday 8.11.2023 / on the road / Anne Pellichero

After two full weeks, the time has come for us to leave for the center of the country. As soon as we are leaving our last meeting with administrative officials early in the morning, we are greeted by sirens. I receive several messages from different sources: The threat of ballistic missiles in the area is real. We’re in the middle of officials and military buildings, so it is important to move fast.

Even though I know Ukraine well and have traveled there a lot, there is still always something new. Traveling in a convoy of three cars means that we have to adapt: Some want a coffee stop or a break, others prefer to stick to the schedule we’ve set ourselves. We pass dozens of grain silos, endless acres of cereal fields, and packed train carriages. The Ukrainian landscape is flat. No mountains, no hills. The view goes on for kilometers. Here and there, we see military convoys and burnt-out cars along the road. Everything is grey and cold. There’s just us and the sound of windscreen wipers for six hours. I feel like I’ve been in this car with my colleague Polina forever. There is this bond between us as women, our visions of the future, our uncertainties, and this deep conviction that with a lot of solidarity and a bit of humor, these dark times will be easier to live in. Together.

Memorial in Dnipro City

Thursday 9.11.2023 / Yuzhnoukrainsk / Polina Kolodiazhna

First stop today in Yuzhnoukrainsk is the meeting with the municipality representatives with six women in the meeting.I had a feeling that this is a city of women. When discussing their experience during the war, I realize how hard it is for me. I remember that feeling of complete disbelief when I thought that the news that the full scale invasion had started was some bad joke, when you are standing in the street in the morning, looking at how hundreds of people with bags and 5-liter water bottles are going to the subway to hide. All these thoughts – to hide, to leave the city or to leave the country – all of them just came to my mind. These women decided to stay and to help others. When the Russians occupied Voznesensk, a city 20 km from Yuzhnoukrainsk, they all gathered together. Some of these women began to live in the community building, calling old people to warn about the air alarm. They provided help to all those who needed it.

After arriving at a local school to install a sensor, we meet a group of very friendly teachers and their headmistress. During coffee, we speak to her about her responsibility for so many children during the war. She tells the story, that one day before the war, older children asked her about her opinion on a potential full scale invasion. She answered that she doesn’t believe that it will ever happen. When the war started the next day, they came to her, said nothing and looked at her. Tears come to my eyes when I listen to this story. She says “that moment I realized that I lied to them and that I let them down”. In the evening, I realize that I will never forget this city, these women from the municipality and especially the headmistress.

Greenpeace is installing a radioactivity measuring point in Yuzhnoukrainsk

Friday 10.11.2023 / Odesa / Shaun Burnie

Odesa always held a fascination for me. We enter the city with a tight schedule of meetings, installation of radiation sensor and background images of a city and region under daily attack from Russian missiles. We see the center of a city of boulevards, trees everywhere and pastel colored buildings. And around the next corner there is suddenly a gap where one of those buildings used to be. Our morning meeting with regional officials stretched over three hours as we were not able to leave the bunker room due to missile warnings. Underground tea and cake with young people – what must it be like to be living like this every day, normality shattered by alerts and explosions?

While we are only a short distance from the Potemkin steps, the location of the famous scene in the Eisenstein film Battleship Potemkin about the 1905 Russian naval mutiny, one part of the team installs a radiation sensor in a fire station, and the others are given the opportunity to visit a modern art gallery. The young curator guides us through the rooms: a small shoe sized box of black metal (missile parts) and neat piles of dust recently swept. The art is gone, apart from a few sculptures – wrapped as if always intended to look that way. Two days before, a Russian ballistic missile blasted its way into the ground outside the main gate and the shock wave damaged the gallery. Only the picture frame wires and name plates remain. I notice one of the artists name: Robert Selskyi, Traces of War. I read afterwards that his revolutionary themed art of the 1930’s included the Potemkin uprising. This is Odesa.

Barricaded windows and a wrapped sculpture at the National Art Museum in Odesa

Saturday 11.11.2023 / Uman, Kyiv / Tobias Muenchmeyer

“Morning has broken” sings Christian, our photographer with a very special taste of music. This morning, which has dawned in the small town of Uman, just in the middle between Odesa and Kyiv, is a very rainy one. Over breakfast, we’re discussing the latest security updates: Missile hits in Kyiv in the early morning, for the first time since weeks neither intercepted nor destroyed by their defense system. Polina looks worried.

We move to Uman Pedagogical College and are welcomed by Vladymyr, its caretaker, a modest man with golden hands. On the way to the classroom I pass a little niche, like a shrine at which portraits of young men and exploded munitions are displayed. “College Graduates who have protected Ukraine from Russian aggression.“ it reads on the top. One of the young men, Sergiy Fedorivskyi with his shy smile, looks exactly like Germany’s legendary football striker, Miroslav Klose. Striker, I think. Since this war, the military terms in football – hitting, shooting, attacking, defending, defeat and victory – sound weird to me.

After less than one hour of preparations, we are moving outside the college. Pavlo stands on a shaky ladder in the pouring rain. When he starts drilling a hole into the college wall for the installation of our radiation sensor, another air alert is sounded …

Sunday 12.11.2023 / Kyiv / Tobias Muenchmeyer

A day without an air alarm. Maybe the first day since we are in Ukraine? However, an alert alone doesn’t really tell you much. You must join various telegram channels to understand what kind of alert it is. Anne and Polina have altered this task. Three times they have called us to go to the shelter immediately, once in Chornobyl, once in Dnipro and once in Odesa where we were already at a meeting in a basement – and were told we shouldn’t leave it until it was over.

It is one of these paradoxical effects of war: Everybody tells you that they got used to the alerts a long time ago, that they are not getting scared and that in most cases they’re not going to a shelter. But at the same time I started to observe people’s reactions to an air alert very closely. When I was drinking coffee with my friend Olha and suddenly an air alert went off, it seemed to me that a kind of invisible blinds were going down and covering her eyes for a tiny moment. The alarm seems like a perfidious reminder: “Russia is still targeting you.”

Bizarre moments of normality: a piano in the hotel lobby

Monday 13.11.2023 / Kyiv / Tobias Muenchmeyer

Across the Kyiv opera house I pass the German Embassy. Tomorrow, I will have a meeting with the Ambassador. The little showcase in front of the Embassy, next to an original piece of the Berlin wall, displays only one poster: “Germany’s Military Help for Ukraine”. An entire zoo of Leopards, Gepards, Marders and Bibers delivered to Ukraine is displayed there. I hope that besides this, the other help Ukraine urgently needs will be displayed soon: Support in green reconstruction by providing a modern and resilient energy system based on renewable energies. When German Minister of Economy Robert Habeck came to Kyiv in April this year, he visited the war-damaged hospital in Horenka which Greenpeace had reconstructed. Solar panels on the roof, heat pumps in the ground – no rocket science, but Habeck was impressed: It’s simple and it works.

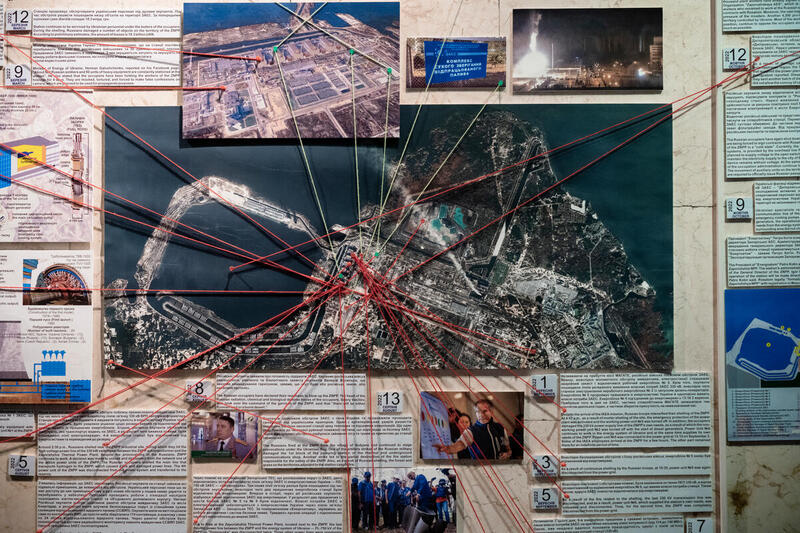

Tuesday 14.11.2023 / Kyiv / Shaun Burnie

My first visit to the Chornobyl museum in Kyiv: The scale of the worst nuclear disaster in history means that it is a place of hundreds of thousands of memories. But today it is also the reality of war that hits you as soon as you enter, you realize that you are not looking at exhibits from 1986 but the remnants from Chornobyl today and the recent Russian occupation on the first day of the full-scale invasion, like a metal box with Russian rations of jars of pickles and anti-personnel mines. A map on the wall tells the story of the attack, seizure and occupation of the Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant by Rosatom and Russian armed forces. Faces of soldiers, engineers, residents of Pripyat gaze at you from behind the protective glass. A group of school kids is visiting, and even during the Russian war, education on this part of history continues…

The Chornobyl museum in Kyiv

Wednesday 15.11.2023 / Kyiv / Shaun Burnie

In the morning we meet with the director of a recent documentary on the Russian attack and occupation of Chornobyl. The vital testimonies of workers in the film who confronted the Russian armed forces is important evidence for future war crimes legal action and I am thankful for this work. Later, Jan and I are listening to one of our Ukraine colleagues who is new to Greenpeace. We learn that three generations ago, his relative grew up near Chornobyl, experiencing a century of hardships, including World War I, the Holodomor famine, the Nazi invasion, and the end of World War II. The village survived all of this but the 1986 radioactive contamination ended its way of life.

Later that evening an opportunity to unwind with dinner with our team. Over one of many beautiful bowls of borscht during our time here and while eating, we each say a few words of appreciation. It really feels like decades of learning since we came here. I am fortunate to gain this knowledge from so many brilliant colleagues. What an honor it is to be able to visit and work with the people of Ukraine.

Borscht

Thursday 16.11.2023 / Kyiv / Tobias Muenchmeyer

Through the hotel window I see a beautiful sunrise above the Olympic Stadium. In 2012, the legendary Iker Casillas of Spain lifted the European Championship’s trophy after a 4:0 final win against Italy. It was a time when Kyiv was in the international news for something else: Football.

Today we are meeting with the Ukrainian NGO Truth Hounds, which has documented human rights violations by the Russian nuclear giant Rosatom. It is frustrating to see that despite the evidence presented by Truth Hounds, yesterday Hungarian Foreign Minister Peter Szijjarto and the chairman of Russian nuclear giant Rosatom, Alexey Likhachev, signed a plan for the completion of the Hungarian Paks nuclear power plant. This is the same Russian state-owned company that was involved in the occupation of the Chernobyl and Zaporizhzhya nuclear power plants from the very beginning. Greenpeace is calling on the EU to finally impose sanctions against Rosatom.

Sunrise over the Olympic Stadium in Kyiv

Friday 17.11.2023 / Kyiv / Tobias Muenchmeyer

The day of the press conference at the “Ukraine Crisis Media Centre” in Kyiv. It is located at the very heart of the city center of Kyiv at the European Square, close to the philharmony. In 2014 it played a key role in the peaceful Maidan protests and I remember the creative chaos taking place there, just hundred meters from the barricades: Artists designing helmets, elderly people bringing boxes with literature for an improvised Maidan library, a poet reciting his own verses, an area to collect warm clothes for the protestors, an old woman playing jazz on a piano, a first aid center in the basement, protestors resting in their sleeping bags, a group of “Maidan university” students analyzing Immanuel Kant’s concept of “Perpetual Peace” – all a bit utopian. I loved it.

10 years later I see my colleagues preparing for our press conference. Shaun and Daryna are discussing some details of the schedule, Jan is reading in his concept notes, Polina is testing the microphone and Pavlo drinks a glass of water. And then it’s turning 12:30 and we go live. For now our nuclear odyssey has come to an end.

Press conference at the “Ukraine Crisis Media Center” in Kyiv