Greenpeace volunteer and founder of youth-led non-profit The Cynefin Group, John Leonard Avenido reveals some of the stories from fishing communities in the Visayas. These fisherfolk provide some of the food that end up in our cupboards and plates, even during this global pandemic. They have been carrying messages of sustainability and calls for food security even prior. Avenido tells us that it has now become even more urgent for us to hear their voices and spread their stories.

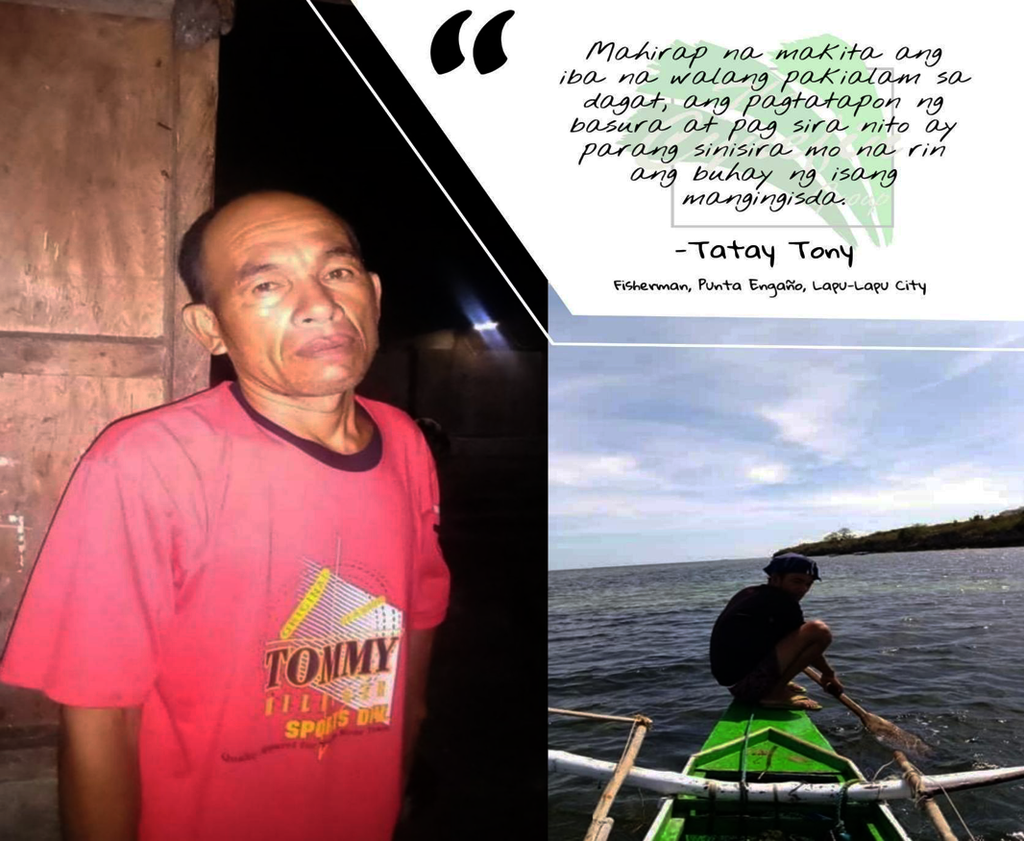

Tatay Tony, A fisherman from Punta Engaño, Lapu-Lapu City

As the current pandemic crippled the country’s economy, one of the sectors that is greatly damaged is the fishing industry. Tatay Tony is just one of the fishermen in Punta Engaño, Lapu-Lapu City, who are widely affected by the current crisis.

He wakes up as early as 6am to get his gear, such as the “panggal,” ready. This fishing trap is set underwater to catch fish for his living. Sadly, panggal won’t work without a bait called “lumot” which he usually has to buy from Cordova, a 3.5-hour-walk from Punta Engaño. His age and the current quarantine guidelines in the city prevent him from buying fish bait.

“Kasagaran sa mga mananagat ari nawad-an ug panginabuhi tungod aning COVID”, Tatay Tony said. (Most of the fishermen here lost their livelihood due to COVID.)

Without the bait, he is forced either to resort to “pamamana” (spearfishing) or, like most other fisherfolk, rely on the relief packages from the local government. But with the size of their family, it is never enough.

“Importante kaayo ang panagat diri nako kay mao ni ang tubdanan sa among panginabuhi. Ari ko nakakuha ug kwarta para makakaon mi taga adlaw, maka palit sa mga palitonon ug makapaskwela sa akong Lima ka anak,” said Tatay Tony. (Fishing is very important for me since it is my primary source of income to feed my family, to buy our daily needs, and to send my five children to school.)

He was 8 years old when Tatay Tony started fishing and remains his primary source of income. It is where he gets resources to send his eldest child to college. The depletion of his daily catch is a continuous problem he’s had to face for the past years.

“Protektahan [nato] ang dagat sama sa pag pangisda nga dili maapektuhan ang mga corals. I-dili ang paggamit ug mga dinamita. I-dili ang paglabay ug basura sa dagat. I-dili ang pagkuha sa mga talagsaong mananap sama sa bao, kay usahay makakita ko na nay manguha ug pawikan nya ila ra ibaligya,” Tatay Tony Said. (Let’s protect the sea through responsible fishing that does not affect the corals, stop the usage of dynamite, stop throwing garbage at sea, stop catching wild marine animals like turtles, because I usually see them catching turtles and then sell it.)

As we continue our unprecedented destruction of our seas, we are not only harming marine life, but also the fisherfolk that rely on them.

Fishing is a cradle in their lives. Without fish, there is no living.

“Kaming wala kahuman sa pagtungha tungod sa kawad-on, kining panagat na ang among panginabuhi,” he argued, “Sakit nga makita nga ang uban walay pagpakabana sa dagat. Ang pagpataka’g labay’g basura ug pag guba sa dagat, sama rakag naguba ug kinabuhi sa mga mananagat.” (Those of us who haven’t finished our education rely on fishing as our livelihood. It’s painful for us to see others not giving a care about the sea. The improper throwing of trash and destroying the sea is like destroying the life of a fisherman.”)

Islanders view, A day in a life story of John Paul Minguito from Cuaming, Bohol

As a son of a fisherman, I am a witness to almost everything about his life. I know the movement beneath the waves, which gives life to our land. This is a day in the life of an islander of Cuaming, Bohol.

At 2am, my father wakes up to head out to sea to catch fish, leaving us peaceful and in deep slumber. When the clock hits 8, I wait on the shore to assist him. There are days when my heart almost sinks upon seeing my father’s catch is only enough to feed us for a day and not to make profit for our other needs. I ask my father, ‘Are these your only catch?’ I can see the weariness behind those tired eyes as he fixes his gear. “No, I already sold lots of them to mamangga,” he replies. Mamangga is a fish-trader on the island. My mother then cooks the fish for breakfast which, for us, will last for dinner. “Fish? Again?” My little sister murmured and I can only feel sorry because there’s nothing we can do. It is the only food available to us.

In the late afternoon, when the tides are low, coastal rice fields and sea grasses show up right on the shore. My friends and I use this chance to make money—looking for shellfishes and selling them. Sadly, seasons aren’t always kind and our luck varies over time. Yet, islanders always adapt to changes.

When the moon is huge and full, my father prepares his “Subid,” a fishing gear used to catch squid. He always manages to catch them in numbers. There are also seasons that we consider as golden seasons in the island, because we expect lots of catch. One of them is the “Limang Subang” or the fifth full moon. During this season, we have this event called “Sobad sa Danggit” where “Danggit” fishes (also called Rabbitfish or Spinefoot) are in their mating season and parade in huge numbers on the sea surface.

After this season, my father again prepares his broken fishing gear, a distinct gear with a lot of huge hooks attached to a thick nylon string. There are various fishing gears to catch various types of fish. We call this one “Kitang”. This gear is widely used by my father almost everyday and in any season. This gear is used to catch ‘katambak’ also called Sweetlip Emperor Fish. The price of this fish is around 170 to 200 pesos per kilo if sold to a fish trader—enough to make profits for our daily needs.

Our island is just small and our fishing practices are closely related to one another. However, there is a practice that made me and my father always feel bad—illegal fishing. Though our laws in fishing strictly prohibit such acts, there are still fishermen who use dynamite, fine-eyed fishing nets and other illegal fishing practices that cause lots of damage, not only to the island’s marine biodiversity, but also to the fishermen. I have witnessed it first-hand, as I had swam deeper in our coastal waters and saw the aftermath of its effects—wide devastation.

To address the worsening situation, I am very much thankful that our island’s Barangay Captain is strictly implementing the ban on these illegal practices and designated an area around the island to become a fish sanctuary. Yet, there are still locals that fish within its borders and I am doing what I can to stop this act.

I am very thankful to live on an island and honored to protect its marine biodiversity against illegal fishing and overexploitation because this is the only place that we depend on—where our island community, Cuaming, makes a living.

Tatay Gil, a fisherman from Pong-oy, San Juan, Leyte

On the eastern coast of the Visayas, fishing is intertwined with the local community’s life. It is their main armament in surviving daily battles to sustain their families’ needs. However, this fate became blurred when the health crisis crippled the country’s economy and affected the region. This situation made the locals greatly appreciate the sea more.

In the small town of Pong-oy, San Juan, Southern Leyte, Tatay Gil is one of the fisherfolk affected by the pandemic, which eventually made him realize how important it is to help save our seas.

“Importante para nako ang pagpanagat kay mao namn jd ni ang ako trabaho og usa ni sa nakapabuhi sa ako pamilya” said Tatay Gil. (“Fishing is important for me because it is already my job and this also supports my family.”)

He has been a witness to the abundance of the sea in the past. Back then, Tatay Gil would celebrate his triumph over a number of catches. But these days, it’s considered lucky when you get one. The current situation that the world is facing should not be an excuse to neglect our seas. He firmly believes that, to save the seas, we should start by taking action.

“Kung pwede, dili maglabog og basura uban sa nagkadaiyang mga chemical sa dagat,” he said, “Ja dili panguhaon nang gagmay na isda og mga corals.” (Please do not throw garbage and chemicals into the sea. And do not get small fishes and corals.”

As fishermen, it is important to take good care of the sea and fish sustainably, because the catch of today will affect the catch of tomorrow. Marine debris, specially plastics, are the main reason for the starvation, severe injury, and even death of 100 million marine animals in the ocean. There are fears that there will be more plastic than fish by 2050. But there is still a chance to save it.

“Dli mamahimong iresponsable kay ang dagat dako og tabang natong mga Tao,” said Tatay Gil, “Makakuha tag mga isda ng mapakaon nato sa ato pamilya. Nakita nato karon sa sitwasyon nato tungod anang covid nga nagkalisod jud ta og ang dagat o mga isda ang usa sa nakatabang nato para naa tay makaon.” (“Not being irresponsible because the sea has huge benefits to us humans”, said Tatay Gil, “Get caught fish that will feed our family. We saw in this situation that because of the Covid [crisis] we suffer and the sea as well as fishes helps give us food to eat.”)

Marine life has benefited the local communities of the region for years. Neglecting to care for it is destroying the lives of fisherfolk like Tatay Gil. With the current pandemic, we have witnessed how the seas provide food for our plates. Together with the healing of the atmosphere, let us not forget that the sea also needs to breathe for a while. Our actions will determine the fate of our ocean and the fishermen that rely on it.

Let’s create a new and #BetterNormal—where everyone can thrive and no one is left behind.

Support The Cynefin Group by following them on their Facebook and Instagram page.