Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of Greenpeace Philippines.

All eyes glued on the scoreboard. Hidiliyn steps forward, grasping the bar with all strength left in her body. She submits in a rack position, exploding the barbell overhead then dropping the weight in an outcry—snatching off the clean and jerk by one point over her opponent. The crowd erupts. In the far south of the Philippines, void of LED screen boards and a stadium, a Lumad girl in the middle of the field bends her knees as if attempting to lift a heavy weight. With no one but herself to cheer, she heaves in 3…2…1… hoisting the liyang atop her head, the gold medal beaming inside her basket: today’s bountiful crops. Like Hidiliyn, the rest of her community lauds in victory.

In a country led by a strongman, a woman bagging the Philippines its first Olympic gold medal harbors a symbolic triumph. Indeed, the imprint of Filipina strength traces even centuries before—from babaylans to revolutionary forces, the Filipina knows to stand in the forefront. Dwelling on the greens of Pantaron is a living testament to this strength: Bai Bibyaon Ligkayan Bigkay, the first woman chieftain of the Manobo tribe. Over two decades ago, Bai Bibyaon, alongside ten Lumad women, led the tribal upsurge against the illegal expansion of a logging company. Yet the vigor displayed by these women daunted the strongman in power, his trolls red-tagging and threatening their lives to stroke his frail ego.

I. Liyang and the burden

As the administration grabs credit for Diaz’s win, the “Oust Duterte” Matrix presented by former Presidential Spokesperson Salvador Panelo in 2019 resurfaced on the internet. On said matrix, Diaz, alongside political and media personalities, was flagged as “enemies of the state” for allegedly plotting the ouster of President Rodrigo Duterte. This prompted Diaz’s outburst on social media as her life became threatened.

In the same year, the Lumad people decried the militarization and extrajudicial killings aggravated by the Martial Law in Mindanao. Troops from the Armed Forces of the Philippines were deployed in their communities for the forcible closure of Lumad schools, denouncing the classrooms as venues for “brainwashing” its students to rebel against the government. Diaz and the Lumad, however, were only among the thousands of victims of this regime’s reckless red-tagging for simply asserting their rights.

II. Liyang and its harvest

Lumad members remain important warriors who dedicate their blood and sweat for their soil to thrive. The liyang (a Manobo term for “woven basket”) is considered essential in Lumad communities as this is where items are stored, especially in placing their harvests gathered from the farmlands they sow. With their communities settling in the interior of Pantaron, the tribes rely heavily on the forests’ ecosystem for survival. The mountain ranges cradle vast species of floras and fauna, and more importantly, their familiarity with its thick terrains provides an efficient advantage against invaders.

Under their lands are preserves of mineral deposits, tantalizing exploitation of large companies. Before persistent attacks, the Lumad are tricked into selling their portions of land in exchange for cheap goods, such as cans of sardines.

III. Liyang and the journey

As Lumad women continue to hoist their liyang, sharpen their weapons, and trek under the heat for hours, we hold on to hope. The difference between the strength of a strongman and a stronger woman is not the weight they carry, but their voice. Voices greater than one man’s greed are the echo of the masses who raise their fists beholding narratives of Hidilyn, Bai Bibyaon, Lumad women, and all other strong women stepped on by brute forces. For every fragile strongman that reigns is a stronger woman who stands in the frontlines; in each one that is silenced, thousands arise to tell her story.

Be one of these voices.

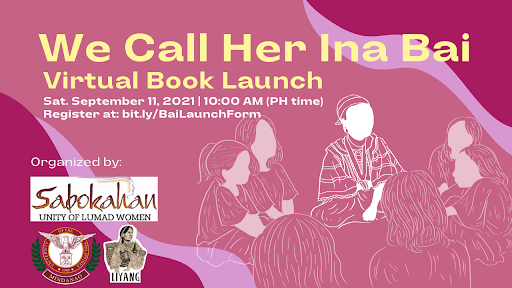

Walk with the Lumad as they tread the greens of Pantaron and fight hand-in-hand as they confront ravagers of their land in the thrilling young adult novel, “We Call Her Ina Bai: How Strong Women are Made,” cultivated by narratives as told by Lumad women leaders, Bai Bibyaon and Sharmaine of Sabokahan Unity of Lumad Women. This book weaves the intergenerational struggles of the Lumad Manobo and how their resistance nurtured their tribes to promote equality among societal and political roles in the community. It is an embrace, from one strong woman to another, that we too can yield weapons and lead a war—and thrive in it. As we flip through its pages and our footprints taint the streets, we open new chapters for women, minorities, and the oppressed to paint their own stories.

Register here to attend our book launch organized by Sabokahan, Liyang Network, and UP Mindanao Department of Social Sciences: bit.ly/bailaunchform

Where to order the book:

Check out these pages to learn more about Sabokahan’s book and campaign work:

- fb.com/InaBaiBook

- IG: @Sabokahan

- FB: @SabokahanLumadWomen

- Twitter: @Sabokahan

- https://www.sabokahan.org

Liyang Network is a local to global advocacy network that amplifies the calls to action of frontline land, environmental and human rights defenders in Mindanao, Philippines. By weaving together our diverse experiences, skills and resources, we unite in their active defense of land, livelihood and self-determination.

Christine Jewel Morano is a sophomore at the University of the Philippines Cebu. She is a member of the Education and Research Committee at Liyang Network, and also a feature writer at Tug-ani, the official student publication of UP Cebu.