When we give a piece of land the chance to breathe, life slowly but surely finds its way back. Animals and plants emerge from the shadows. One might see weeds, soon, shrubs take root, reaching towards the sky. Trees begin to rise, their branches stretching out in a promise of tomorrow. Before your eyes, a majestic forest is born.

This beautiful rebirth brings a cascade of benefits: the soil becomes richer, teeming with diverse life forms. The land’s ability to retain precious water improves, and it stands strong against erosion. Each of these benefits is underpinned by complex ecological systems that work together to create a more resilient and sustainable environment.

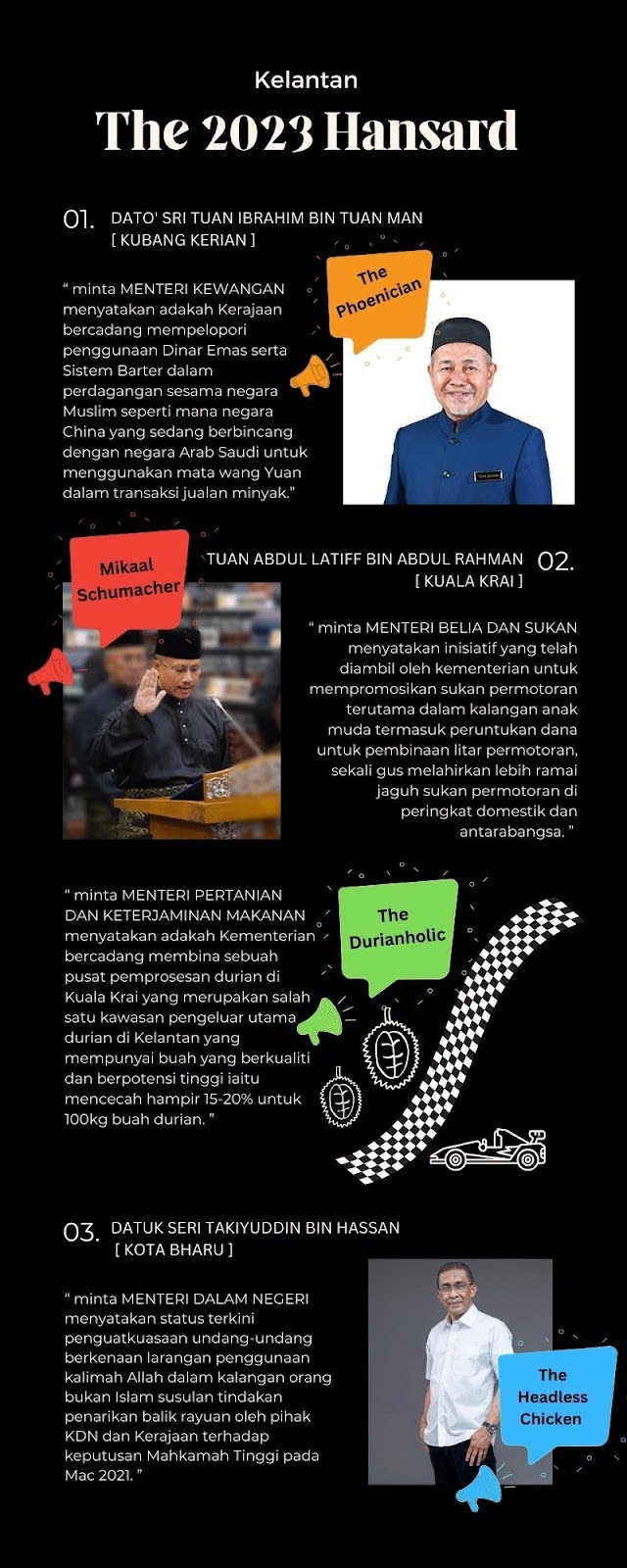

ust as a forest needs strong ecosystems to flourish, successful governance requires robust systems to thrive. Unfortunately, some odd questions raised by Members of Parliament in the 2023 Hansard demonstrate how challenging it is to safeguard Kelantan’s natural environment.

These questions, gleaned from the Hansard record, serve as stark reminders of Kelantan’s dire environmental predicament due to anthropogenic activity. The grim reality paints a troubling picture of our deeply flawed relationship with nature: pollutant emissions choke the air, rampant deforestation strips the land bare, agricultural monoculture destroys biodiversity, and ineffectual governance fails to address these issues. Imagine we had access to the ADUN and EXCO members’ Hansard records as well. Would the environment’s fate change?

For those who are unfamiliar with ‘Hansard’:

Hansard, provides a comprehensive and largely verbatim account of the proceedings in Parliament. This document meticulously captures the statements made by Members, subsequently undergoing a process of editorial refinement to eliminate redundancies and rectify apparent errors, while maintaining the integrity of the original discourse. Furthermore, Hansard serves as a repository for the decisions reached during parliamentary sessions and meticulously documents the voting patterns of Members in Divisions, thereby ensuring a thorough and accurate representation of the legislative process.

Too, it invites us to ponder: Have our elected Ministers truly been the stewards our state deserves?

Even in the heart of dense forests, it’s getting warmer.

The Nenggiri-by-election is underway. These are critical times for Kelantan’s forests. In places like Gua Musang, wildlife, and indigenous people are locked in a fierce struggle. Encroachment, mining, and logging are rapidly reshaping the future of these vital ecosystems. The state government is de-gazetting a large area of its reserve forests. This process removes the protected status of these lands, allowing for alternative uses that may potentially yield financial benefits for the state without heeding the consequences this has on communities living in the area.

In other places, the hydroelectric power plant project has taken away not merely the forest, but also homes of the 1,200 forest guardians that had been passed down for generations. One such place is Nenggiri. This displacement has resulted in significant socio-economic repercussions for these indigenous communities. The loss of ancestral lands disrupts their traditional way of life, cultural practices, and sustainable resource management systems. Is the resettlement sufficient as their compensation? Furthermore, it raises critical questions about the balance between economic development and environmental conservation.

Kelantan, between 2017 and 2021, ranked among the Top 3 states for deforestation after Sarawak (111,888 hectares) and Pahang (104,540 hectares), accounting for 54,987 hectares. To contextualise this information, consider that Singapore’s 1822 land reclamation covered 58,150 hectares. The drastic reduction in forest cover in Kelantan poses a critical environmental threat.

Planting a few isolated elements is akin to forcing yourself to focus solely on a single body part. It’s simply not effective. Just as our body is an intricate, interconnected system, our forests deserve the same holistic approach.

The widespread problem of unsustainable monoculture plantations for oil palm has been replaced. RimbaWatch’s report shows that palm oil cultivation is no longer the primary driver of deforestation in Malaysia. They are only responsible for about a third of the cleared land. The real deal now is timber plantations. Specifically, monoculture plantations have been established within forest reserves. These plantations are filled with species such as timber latex clones, Acacia, and Eucalyptus, which are cultivated for their commercial timber value.

Taking a monodominant Musang King Durian plantation as an example, all photosynthesis is concentrated in the emerging stratum, creating thermodynamic effects contrary to water circulation. With no vegetation in the lower strata, dry wind flows freely close to the ground. Without photosynthesis and transpiration, the temperature near the ground rises, creating negative gradients.The soil loses water due to temperature and moisture differences, leading to degradation, compaction, and desertification.

Soil erosion is not limited to the depletion of arable land. This phenomenon has resulted in elevated levels of pollution and sedimentation in streams and rivers, leading to the obstruction of waterways and subsequent declines in fish populations and other aquatic species. Also, degraded lands frequently exhibit diminished water retention capacity, thereby exacerbating flooding incidents. Instead of mimicking the natural dynamics of a thriving forest in agriculture, we reproduce the conditions of crisis.

In addition to the aforementioned concerns, the most critical issue pertains to the assertion by certain jurisdictions that monoculture plantations should be classified as integral components of forest ecosystems. Due to the ambiguity surrounding the definition of ‘forest cover,’ these States have exploited this lack of clarity to submit questionable reports. Subsequently, they have expressed unwarranted pride in their purported “reforestation” initiatives.

Pests are called ‘Inspection Agents of the Life Process Optimisation Department’ by Ernst Götsch. Similarly, flash floods should be considered as ‘Hermes’.

The issue most frequently brought to attention pertains to flooding, with 27 instances of mention. Flood mitigation strategies were referenced 12 times. Given the current anthropogenic environmental crisis, ministerial efforts appear to be directed towards addressing the effects of flooding, rather than identifying and addressing its root cause: the ramifications of extensive deforestation within the state.

The construction site of Phase 1 of the Integrated River Basin Development Project (PLSB) in Tunjong serves as a prime illustration of this matter. The project has been allocated a budget of RM699 million. On August 3, the Prime Minister conducted an official site visit and stated that, notwithstanding the project’s completion, it does not guarantee the complete elimination of flooding in the affected areas.

“Do not pursue a vocation that harms humans and nature. Do not invest in companies that deprive others of their chance to live. Choose a vocation that helps realise your ideal of compassion.” – Thich Nhat Hanh

The indigenous communities, despite their deep connection to the land and sustainable practices, are often overlooked in disaster relief and climate change adaptation strategies. Their vulnerability is further exacerbated by the lack of legal recognition of their rights and traditional territories.

These communities often possess invaluable traditional ecological knowledge that could contribute significantly to effective environmental management and climate change mitigation. However, their exclusion from decision-making processes and compensation schemes not only violates their fundamental rights but also deprives society of their unique insights and sustainable practices.

Greenpeace Malaysia hereby advocates for the implementation of a comprehensive forestry law. This proposed legislation aims to address the multifaceted aspects of forest management, conservation, and sustainable utilisation within the nation. It is imperative that such a law be enacted to ensure the long-term preservation of our natural resources and to establish a robust regulatory framework for the forestry sector.

- Resolve the ambiguous definitions of forest-related terminology in the Forestry Legislation, such as “forest cover”, “tree cover”, and many more.

- Appoint competent leadership and personnel within the forestry department who are proficient in environmental matters.

- Establish an independent monitoring and auditing system within the state government

- Diverse agriculture with biodiversity-promoting measures is more resilient to global challenges and crises. It ensures that the functioning of agricultural ecosystems is maintained and thus provides sustainable productivity and greater food security.

- Implement a transparent approval process for forestry certification, revise and harmonise the specificities surrounding the rules and regulations in accordance with globally recognised standards.

- Advocate that all nature restoration and protection measures affecting Indigenous lands and traditional territories should be planned and executed in collaboration with IPLCs in a participative approach that respects and integrates their perspectives and invaluable and irreplaceable knowledge. These measures should also focus on areas that are critical for conserving biocultural diversity, i. e. biodiversity, language, cultural and knowledge systems. This should explicitly be reflected in the ongoing revisions of national biodiversity strategies and action plans.

- Ensure that gazettes are freely and easily available to enable independent monitoring of forest changes, allowing concerned citizens to check the status of Permanent Reserved Forests (PRFs) in their vicinity.

- The federal government has implemented a substantial increase in the ecological fund transfer (EFT) for biodiversity conservation, elevating it from RM70 million in 2021 to RM200 million in 2024, representing a significant increase of over 185 percent. Notwithstanding this considerable augmentation, the current allocation remains insufficient to address the comprehensive needs of biodiversity conservation efforts. Moreover, the EFT be formally integrated into a structured conservation financial regulatory framework to ensure its long-term efficacy and sustainability.