The worsening climate crisis is threatening Thailand’s oceans. And with destructive fishing, onshore and offshore industrial projects, and a lack of government plans for climate action, more and more people are suffering in this global crisis.

As the Rainbow Warrior sails around Thailand to raise awareness about these threats, we have connected with the communities who are experiencing firsthand the dangers of this rapidly changing marine ecosystem. These ordinary people who live in coastal communities are gravely affected by government policies and development projects that endanger their livelihood. Now, they are rising together to protect their homes.

Meet the Ocean Defenders of Thailand:

Somchok Jungjaturant – Phato Conservation Network

“I was born, raised, and educated in Phato. I will probably die here, fighting against the land bridge,” says Somchok Jungjatruran, or Chok.

Chok owns a durian orchard in Phato, Chumphon, where a landbridge is being proposed to be built, along with a large industrial estate. While Phato isn’t a coastal community, it is ecologically linked to rivers, forests, and the sea.

“Phato is a magical land, halfway between the Andaman Sea and the Gulf of Thailand, ideal for high-value crops like durian. Lang Suan district, on the Gulf side, is about 40 km away, while Ranong, on the Andaman side, is about 25 km.This central location brings rain from both the east and west. Phato’s mountainous terrain and basin shape make it suitable for agriculture, with abundant forests like Pak Song, Pang Wan, Phato, and Phra Rak, the source of the Lang Suan River. We have rich soil, water, wildlife, and plants.”

Chok and the Phato community established the Phato Conservation Network’ due to the changing direction of the land bridge project, from the NCPO government to the current one. They decided to study it themselves, comparing it to the Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council report under the Office of Transport and Traffic Policy and Planning. They formed a network, initially for those affected, now focused on preserving Phato as a legacy for future generations and a national treasure.

“I want to emphasize that forests, rivers, and seas don’t belong to the government, but to the Thai people.”

Chok concludes firmly, “I want to determine our future based on our local potential. We’re not against development. Phato’s slogan is ‘Green mountains, rafting, mist, beautiful waterfalls, famous fruits.’

“Phato is abundant in natural resources. We live harmoniously with nature, with rich soil, water, and air. Phato is perfect for high-value agriculture. We don’t need an industrial estate here. Any development should align with our local potential.”

Khairiyah Rahmanyah – Daughter of the Chana Sea

Khairiyah Rahmanyah, or Yah, had just turned 18 when she made national headlines. Yah is a fisherman’s daughter from Chana, Songkhla, who campaigned for the government to revoke the cabinet resolution to build the Chana Industrial Estate. She didn’t want to see her abundant coastal home become an industrial zone.

“We live in a good environment and want our future generations to experience the same. This is what we hold onto,” Yah says.

Most people in Ban Suan Gong, including Yah’s parents, are fishermen. Those without boats fish with nets or spears at night. Yah helps her parents pull the boat, remove crabs from nets, and sell the catch.

“The sea doesn’t just support our community, but the entire country and region. Fishing boats sell seafood to markets and restaurants in Bangkok and other provinces, as well as in Malaysia, Singapore, Japan, and South Korea,” Yah explains.

During the 4-year struggle of the Chana Rak Thin Network, from protests and sit-ins in front of the Government House to facing legal charges for exercising their freedom of expression, the community voiced concerns about the unfairness of the public hearing process and the potential environmental and livelihood impacts of the industrial estate, especially on the sea they depend on. Yah and the Chana community demanded the government postpone the project and conduct a thorough Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA).

Currently, the Chana community envisions their future through community cooperation to propose policies they truly have a say in. The Voice of Chana report reveals that Chana’s sea and coast are home to hundreds of economically and ecologically valuable marine species, highlighting biodiversity and a crucial income source for local fishermen and related occupations, as well as food security for the local, national, and international levels. This confirms what the community has been fighting for and voicing for years.

Matom Sinsuwan – Displaced Thai Fisherman

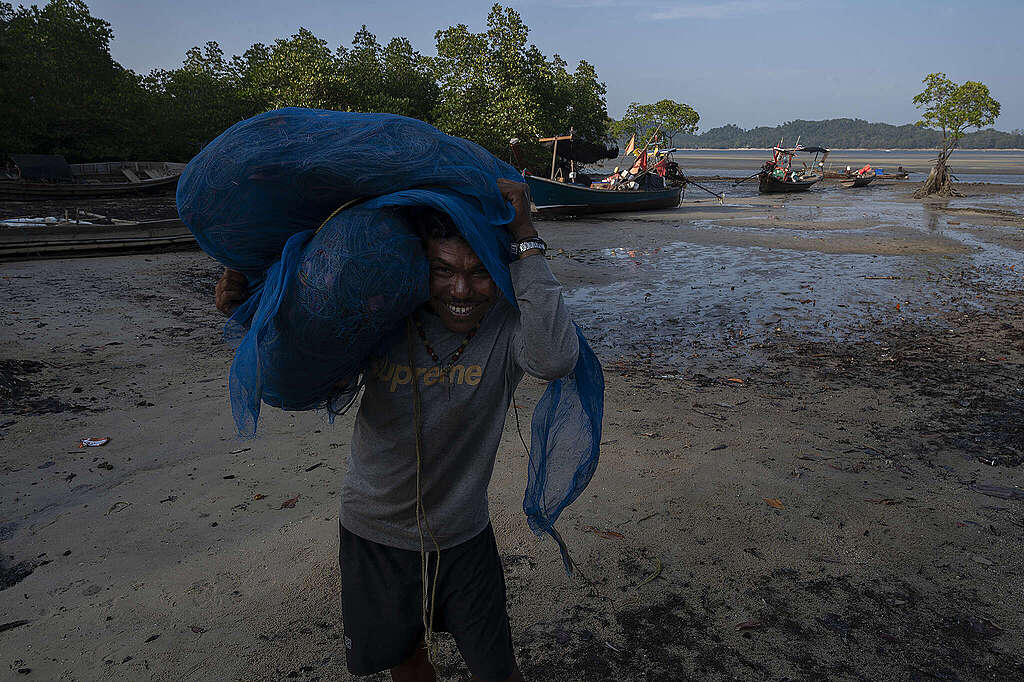

Rajakrud, Ranong is another key location for the landbridge project. We spoke with coastal communities there, who expressed concerns about the impact on resources, livelihoods, and their homes, which are likely to become sites for large industrial estates and a deep-sea port in Ao Ang. These concerns are especially strong among the small fishing village of displaced Thai people who have long relied on the sea but are often neglected by the government.

Tom Sinsuwan, or Ma Tom, says she moved to Moo 7, Ban Huai Pling, 30 years ago and built her family there. She was a displaced Thai person who was missed in surveys and moved there before having an ID card, which she obtained at 40 after advocating for it.

“Before we were granted ID cards, we walked to the Government House, over 5,000 of us. This led to displaced Thai people gaining rights through ID cards, but around 2-3 thousand people in Moo 7 are still considered as displaced persons.”

Ma Tom shares her views on large-scale projects and her vision for the future of her children and community:

“I want to signal to the government that before implementing any development projects, please ensure community rights are protected so people can live well and make a living. Those without ID cards can’t work outside and are confined to Ao Ang, which is abundant and suitable for small-scale fishing.”

“Even though we’re old, we want to preserve this for our children. They haven’t had a chance to access higher education; getting jobs in big projects requires degrees. Our children, at best high school graduates, need to work as they can’t afford further education.”

“I want our home to become a World Heritage site, attracting tourists and generating income for the community. I want the resources and the sea to be a legacy for our children, so they can make a living here. We have beautiful scenery,mangroves, crabs, shellfish, shrimp, and fish.”

Somchok Taleluk – Moken Community Leader on Koh Phayam

Many know Koh Phayam as a tourist island with beautiful seas, clear water, and abundant nature. However, a small corner of this island is home to the Moken, an indigenous group who settled in a small village on Koh Phayam, Ranong, after the 2004 tsunami. They are an indigenous group whose voices are unheard, whose rights are unrecognized, and who are always overlooked when development projects arise, even though they might be among the most affected.

At the entrance to the Moken village, we met Au, or Somchok Taleluk, the community leader. He told us there are about 200 Moken people in the village. Their lives haven’t changed much; most don’t have ID cards and lack basic rights. Many Moken people are hesitant to claim their rights and continue their lives as sea people in this village.

“I was born and educated in Ranong. As a teenager, I moved to Koh Phayam after the tsunami and started a family here. Before getting an ID card, I felt rootless, stateless, and the government didn’t pay much attention.”

“Those without ID cards in the Moken village are still demanding their rights. We help them submit documents, gather information, and find evidence of their birth in Thailand to submit to the district office.”

‘Sea people’ is how Au describes himself and the Moken on Koh Phayam. Their lives are deeply intertwined with the sea, especially fishing, their main source of income.

“15-20 years ago, fishing was very different. We used to catch much more fish. This affects the Moken, who might have to find jobs on land, which will be even harder if the land bridge is built,” Au says.

Au explains that most Moken people don’t understand the landbridge or the deep-sea port near Koh Phayam. During the public hearing, the government didn’t consult the villagers, and the community still doesn’t know enough information about it.

Justice for the Ocean

From the stories of Thailand’s Ocean Defenders, we see a huge gap between the government’s policies and the coastal community’s well-being. These vulnerable groups whose lives depend on the ocean don’t get to participate in important conversations and policy-making that shape their future.

While Thailand has a marine ecosystem protection zoning system, most areas are within marine national parks and reserves, designated and managed by specific government agencies. This leaves communities with little or no participation in protecting and managing resources or incorporating local knowledge into marine protected areas.

The Rainbow Warrior Ship Tour 2024: Ocean Justice aims to spark widespread discussion about public policies regarding community rights to participate in protected area and resource management, to protect coastal and marine resources while ensuring sustainable use.

Add your name to call on leaders to create new ocean sanctuaries and protect our blue planet.

Add your nameKawits Phannapanukul is a Digital Campaigner for Greenpeace Southeast Asia