“How f*cked are we, really?”

These are difficult times to be an environmental scientist. One of the world’s most powerful leaders is working to dismantle significant research institutions, and the spread of fake news has made authentic science more important than ever.

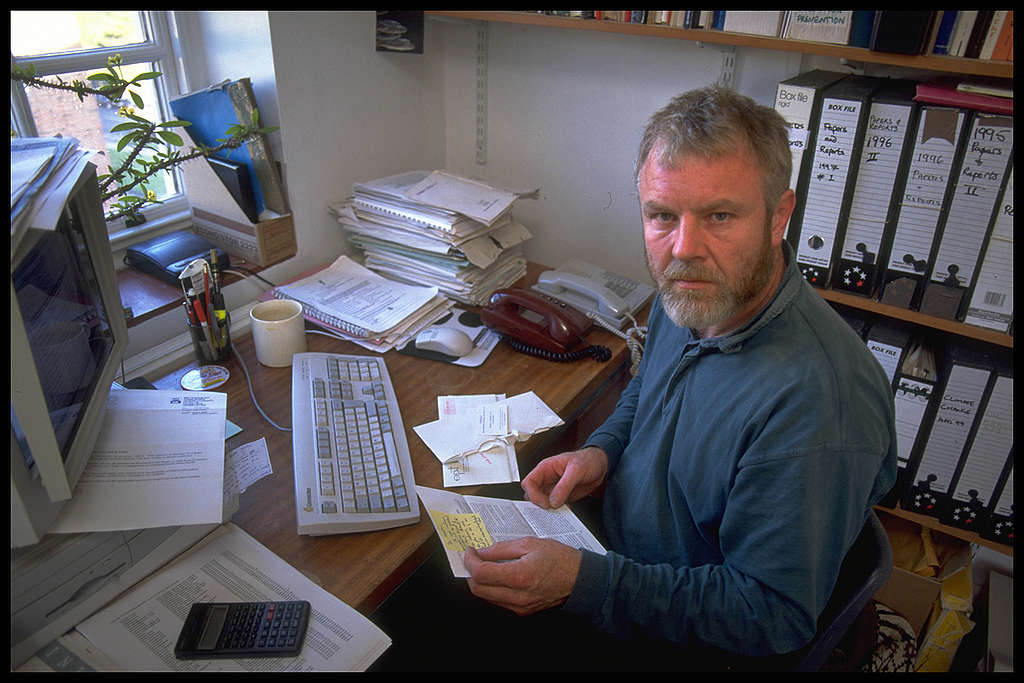

We talked to Dr. Paul Johnston, who’s worked in Greenpeace’s Science Unit for over 30 years and founded our Research Lab, about how to deal with climate deniers and what the future holds for our planet.

As an environmental scientist working for Greenpeace, what is it that you do?

The short answer is an awful lot of things. The variation is what makes this job interesting. In the last fortnight the science unit has looked at pesticides in food, analysed reports on carbon storage, nitrogen pollution in animal agriculture, modelled air pollution, sampled oceans looking for plastic particles, and done some analysis of hazardous chemicals in children’s toys in Russia.

We basically offer information to every campaign Greenpeace runs and try to bear witness to environmental damage through scientific research. If you had to summarise it into one topic, I’d say it’s ‘environmental forensic chemistry’.

We’re seeing the headline “Hottest Year on Record” with increasing frequency — NASA data confirms this. On a scale of 1 to 10, how worried should we be about the warming climate?

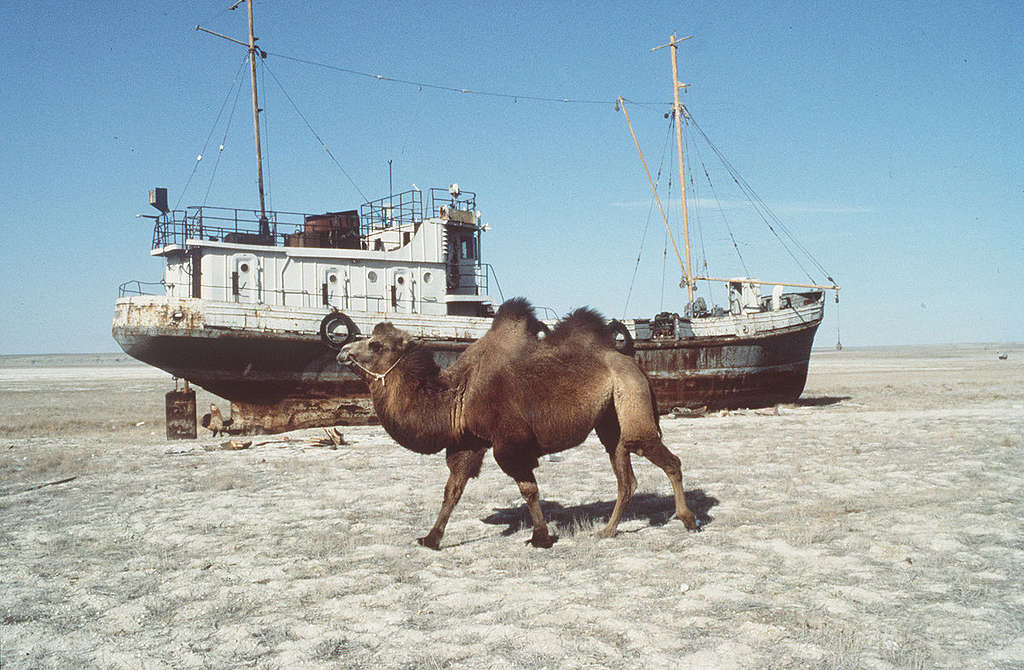

Very worried indeed. It merits at least an 11. We’re in the grip of something that will fundamentally change the world we live in and the world our children will inherit. Sea level rise, food insecurity and extreme weather are going to reach critical proportions this century. We have the means to change this, we just need to implement them.

What’s your end-of-the-world scenario if we don’t keep global temperatures below 1.5ºC as per the Paris Agreement?

That’s tricky to predict. The world will cease to exist as we know it. We’re already committed to a certain amount of change; no-one knows how much yet, but we can be sure that this new climate won’t support life as it exists today.

If you want a nightmare scenario, there’ll be profound social change. Technical advances won’t save us. Our ability to cope depends on how much we can afford, which will increase inequalities between communities. Those with the least will be the hardest hit. The more developed world will put up borders, there’ll likely be wars over resources — it won’t lead to a global human society working towards a common need.

Humans are incredibly adaptable, but this will push that ability to its limit. We have evidence of climate change coinciding with the collapse of ancient civilisations in the Middle East and Mesoamerica as their land became unable to support their populations.

It might not be recognisable to us, but life will go on. Even if we go back to first principles and evolving again, the planet will survive.

And if we do manage to take action in time? Will the world be magically saved: will forests be replenished, will the Arctic stop melting…?

Even if we stopped burning all fossil fuels tomorrow, we’re committed to a certain level of change already. All we can hope for is to minimise the amount of change. There’s no magic wand, the planet won’t return to the way it was, but it might stabilise in a new state.

If I ran out of optimism I’d struggle to get up in the morning, but I still don’t believe in fairy tales with a happy ending. It’s either we continue as we are, and watch as everything gets worse, or we act now to try and minimise the impact on us and other species.

What do you say to someone who doesn’t believe in climate change?

This isn’t a theory that’s up for debate; it’s based on lots of evidence, compiled by thousands of scientists. They’re denying a body of science that stretches back to the late 1800s. Continuing to believe otherwise is delusional, simply delusional. There’s no room for doubt. I kind of feel sorry for anyone who can’t see that.

What scientific concepts do people often get wrong that really annoys you?

It irks me when people see scientists as somehow a breed apart from regular folk; the idea that it’s all very complicated and our word is God. We’re human beings, prone to errors and influences and our brains have limitations too! We shouldn’t take the uncertainty out of science; removing all the gaps and presenting a theory as fact sets scientists against each and just confuses people.

The view that some scientists have that we need to manipulate the planet in order to fix it is another one that bothers me. We need to be wary of false solutions like geoengineering. I’ve just read a paper that outlines plans to pump cold water into the Arctic to try and refreeze the ice-cap. It’s totally mad! This old style of thinking believes the Earth operates like a machine, but that’s not how natural systems operate.

Of all the terrible things that are happening in the world — poverty, war, lack of universal education and healthcare — why is environmental protection the most important thing for a scientist to work on?

You can’t scale importance. There are lots of things to be working on, environmental science is just the thing that’s most appropriate for me personally. It reflects my interests and passions and how I would like to see the planet preserved for the future. These things are all connected. For a scientist, I think it’s best to pick an area that’s most relevant for you to work in.

Environmental science is most likely to be an underrepresented field; sidelined because it’s a complex subject that’s inconvenient and difficult, and it doesn’t bring financial rewards. You don’t necessarily achieve fame by researching air pollution…

We’ve not been good at protecting our environment so far, but I hope to see that change. It’s a huge privilege to be a small part of this great continuum of people contributing to increasing humanity’s collective knowledge about everything.

How can we engage in a discussion about climate change or the environment without sounding too gloomy?

Seeing some of the changes that have already taken place in the 30 years since I started, like the London convention to stop dumping waste at sea, the Stockholm convention to regulate organic pollutants, and the work the IPCC is doing to inform people about climate change — that’s what brings me hope. There have always been thousands of problems but we’re getting much better at identifying them and addressing them.

We’re now taken far more seriously and not laughed at for caring about biodiversity and the need to protect the natural world. We shouldn’t be pessimistic that we haven’t fixed the planet yet: we’ve made significant progress in some areas, and that gives me optimism that we can do the same in others.

If there’s one thing that everyone could do today to help protect the environment, what would that be?

Just stop and think about the impact we are having on the planet and systems around us. Think about how you’re living your life; how much waste you’re producing, how far you’re travelling, what food you eat, what you’re buying — it’s all significant and it can make a difference.

Try to influence others to think the same way: put pressure on corporations, challenge retailers. There are few better ways to try and make a difference than the willingness to get out there and shout, loudly but peacefully. Most people haven’t even thought about it. It’s tricky to persuade people to rethink their world view, or to even think about a world view in the first place, but it’s what needs to happen for us to change.

This Saturday is Earth Day (22 April), and also the inaugural March for Science — a global movement to defend the role science plays in our health, safety, economies, and governments. Apart from the obvious, why are you supporting the Science March today?

It’s heartening to see that scientists, who are renowned for sticking to the narrow confines of lab coats and never veering into politics, are feeling alarmed enough to demonstrate. Our freedom to experiment is being curtailed by funding restrictions and led by corporate interests influencing science for commercial gain. Representing vested interests is not science.

Our duty as scientists is to go where the evidence is pointing, we have a responsibility to provide the truth. I want to see science where we pursued knowledge for its own sake. Learning and education is not a commodity, it’s an investment in the public good. Science needs to serve society, rather than corporate and political interests.

Paul was interviewed by Chiara Milford, an editor for Greenpeace International. Answers were edited for clarity.