A photographer looks back at Greenpeace’s early years

From 1974 to 1982, I served as photographer on Greenpeace campaigns. This is the third collection of memories inspired by photographs of early ecology actions. Check out the first and second editions in this series too.

Open mine at Tasu

This open pit iron and copper mine was located in Haida First Nation territory, at Tasu, British Columbia, on the west coast of Haida Gwaii, in the Gulf of Alaska, 200-km from the Canadian coast. The first Greenpeace vessel, the halibut fish boat Phyllis Cormack, stopped here on the 1971 nuclear bomb mission and again during the 1975 whale campaign. In 1975, we had spent all our money just to get the ship launched, and we were stopping into coastal communities, selling T-shirts and raffle tickets to raise money for expenses.

Astonishingly, when we arrived in this tiny island outpost, two Buddhist monks met us on the dock. We were all flabbergasted. The monks gave us a flag, carried from Tibet, adorned with animal figures, “for the emancipation of all sentient beings.” This felt auspicious enough, but trundling behind the monks, a fragile old man approached the boat. This was the camp’s handyman, who was also Bob Hunter’s long-lost, beloved Uncle Ernie, whom he had not seen since childhood. As a child, Hunter had lost his father, Ernie’s brother, and he now fell into his uncle’s arms, sobbing. Later, at the mining camp bunkhouse, the monks returned, tapped on the window, and pointed to a bright double rainbow arching through the bay and landing on the Phyllis Cormack, which of course we took as another auspicious sign.

I climbed the upland hill to get this photograph of the inlet and mine, operated by Falconbridge mining company, notorious for mining disasters dating back to the 1950s. Four years after this photograph was taken, four miners were crushed to death in a Falconbridge mine in Eastern Canada. Mining — a core activity of our industrial culture — devastates ecosystems, including water pollution from leaching chemicals.

Whirlpools

As we arrived back to the Canadian coast after our 1975 confrontation with Russian whalers in the Pacific, Captain Cormack took us through a passage known as the Yucluta Rapids, winding through the small islands between the mainland and Vancouver Island.

Pacific tidal water flows around both the north and south ends of Vancouver Island, meeting in the middle, picking up speed through narrow channels and clashing in whirlpools, eddies, and standing walls of water, two meters high. The tidal rapids drag bottom fish up from the sea bed and toss them about on the surface, attracting hungry eagles that gather in the shoreline fir trees.

Fresh mountain water flows into the channels and sits on top of the heavier ocean brine. Logs not buoyant enough to float in freshwater sink to the denser saltwater a meter or more below, creating invisible hazards for boats. The channel turns 90° near where this photograph was taken, setting up large whirlpools.

A 1792 journal entry from Spanish ship Sutil tells how the Salish inhabitants advised the Spanish crew to wait for slack tide to pass through this channel. The impatient adventurers departed early, got caught in the whirlpools, and nearly capsized, but survived. Not all ships have been so fortunate. In 1972, a Life magazine journalist and three companions attempted to navigate the rapids in a 40-foot outrigger canoe. Three of the four drowned in the whirlpools. Our Captain made sure we all knew this story.

I learned during this trip that Captain John Cormack had a deep, familial relationship with the Indigenous nations along the coast. We always felt welcomed by our Salish hosts and honoured to be Cormack’s ragtag crew. Our skipper knew well when to pass safely through the Yuculta rapids, while the water still churned enough to send shivers through his crew.

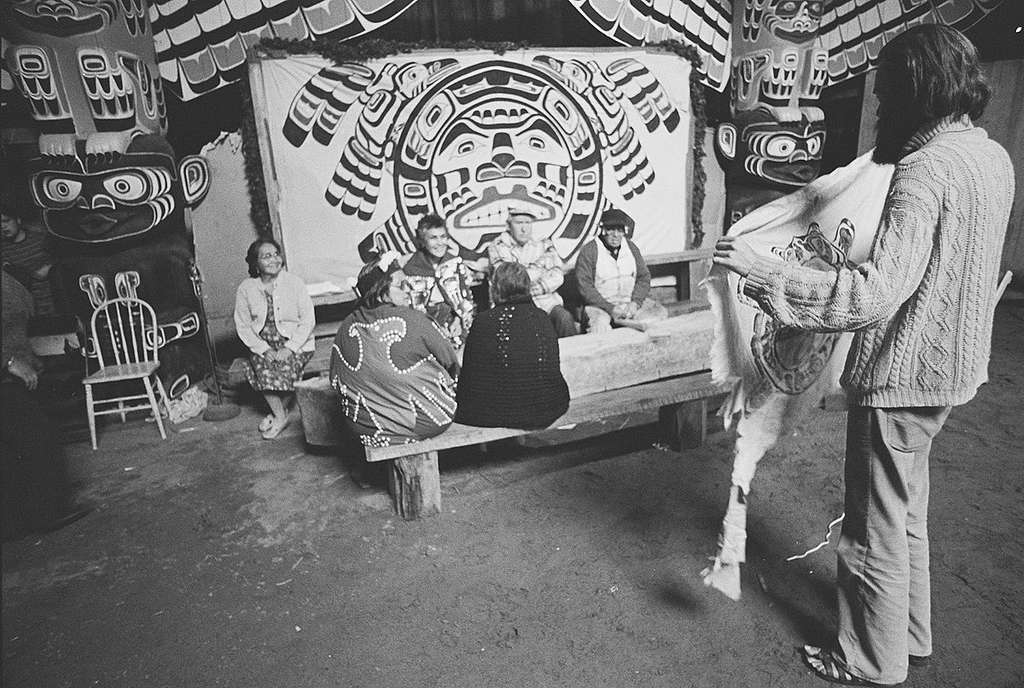

Bob Hunter returning the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw flag

In July 1975, Greenpeace returned a Sisiutl flag — bearing an ancient crest of an ocean being who represents guidance and protection from harmful energies — to the Yalis Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw community in Alert Bay. They had given us the flag to fly following the initial Greenpeace campaign in 1971. In the intervening years, Greenpeace artists had re-painted the flag, and the Yalis community requested that Greenpeace discontinue using the re-painted flag.

Forty years later, at a ceremony in Alert Bay, the community granted Greenpeace the rights to carry a new Sisiutl flag they had designed. Below is the 2015 re-creation the traditional Sisiutl symbol by renowned Kwakwaka’wakw artist Beau Dick.

James Bay, Phyllis Cormack

The whale campaign in 1975 began a monumental transition of Greenpeace from a small, shoe-string, Canadian peace and ecology protest group, into an international network. Prior to 1975, we had very little money, were usually in debt, and everyone working was a volunteer. No one was paid a salary. In 1975, we had to chase down and locate the Russian whalers with the small fish boat, Phyllis Cormack (on the right), which could only travel half the speed of the whaling fleets. With a bit of trickery and luck, we had managed to find and confront the whalers, but we suspected that we would need a faster vessel thereafter. The popular, international success of the 1975 confrontation allowed us to raise enough money to commission and launch the larger, faster James Bay, a Canadian Cold-War-era minesweeper.

We had just spent the entire year preparing for the second campaign against commercial whaling. The James Bay had to be outfitted, repaired, cleaned, and painted. We loaned the Phyllis Cormack to the Mendocino Whale War group in California, who would patrol the coast, and we were set to take the James Bay into the mid-Pacific. We launched the two vessels from Vancouver on June 13, 1976, but we still had work to do on the minesweeper, so we put into the port of Sydney on Vancouver Island. Walking into town for supplies, I turned and saw the two ships together for the first time, a stunning sight that seemed to embody the transition we had experienced over the previous year, the original Greenpeace and the future Greenpeace side by side, shimmering with promise.

Canadian police board the James Bay

By Sunday, June 20, 1976, we had completed all repairs on the James Bay. We rounded the southern tip of Vancouver Island, for the Pacific, but stopped in the port of Bamfield to call our new ally, a sympathetic US Congressman, who had agreed to supply us with coordinates for the two Soviet whaling fleets, Dalniy Vostok and Vladivostok, with some two dozen harpoon ships. When our new ally communicated in code using pages from the San Francisco phone book, we felt as if we were caught up in the delicacy of international espionage. Our American friends could not give us positions for the Japanese whalers, who were US allies. To find the Japanese fleets, we were on our own, for now. As we prepared to depart Bamfield, however, a Canadian Coast Guard cutter blocked our exit, and an RCMP officer shouted, “I’m seizing this vessel.”

The officer charged us with failing to complete a customs form in Vancouver and demanded to see our bonded goods, the custom-exempt items that could only be opened outside Canadian territory. They found the bonded goods to be secure and legal, but held us in custody all day as our team in Vancouver sorted out the petty customs infraction, for which we paid a $400 fine. Bob Hunter released a media statement, admonishing the “small-minded and niggling Canadian government” for siding with the whalers.

We departed that night, southwest for the Mendocino sea mounts. Ted Haggarty, chief engineer, had served on the ship in the Canadian Navy. On the first morning out of Bamfield, he informed us the minesweeper was farther from the coast of Canada than it had ever been in Naval service.

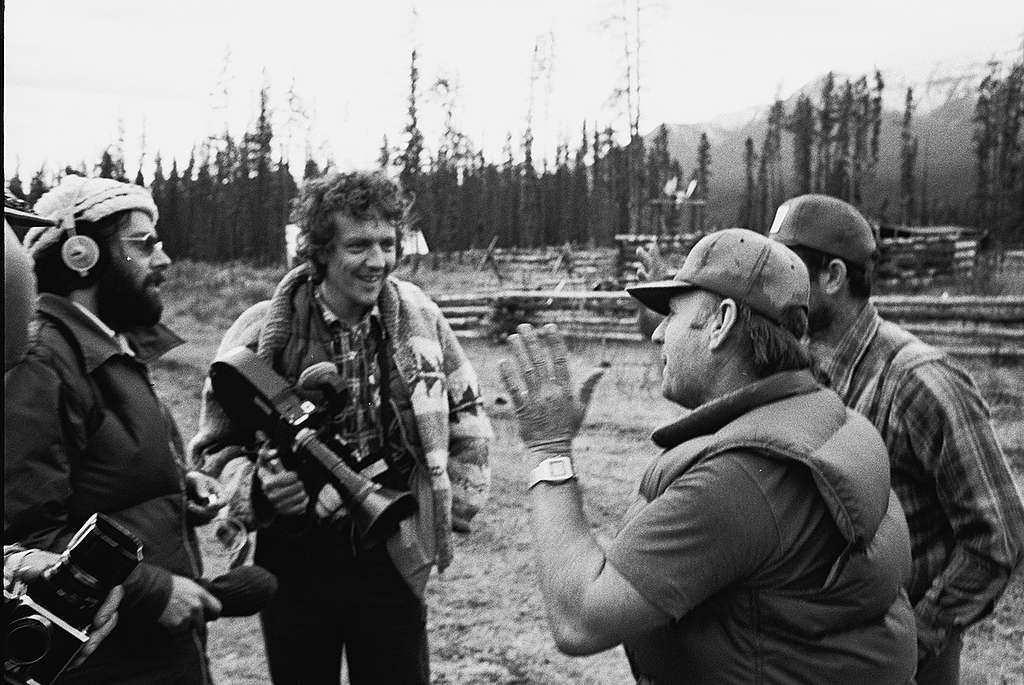

Trophy hunting campaign

This image was taken during the first Greenpeace trophy hunting campaign in 1979 in Spatsizi Wilderness Park, B.C., Canada. Trophy hunting outfitter Ray Collingwood is telling Greenpeace filmmaker Michael Chechik and cameraman Colin Wedgewood to leave his land. Chechik was later severely beaten during a midnight raid on their camp by hunting guides, the first serious casualty of Greenpeace campaigns.

Activist/naturalist Judy Drake — who raised orphan wolves — had proposed the trophy hunting campaign in an alliance with the Hagwilget Village First Nation, who wanted to stop trophy hunting in the 1.2-million-acre Spatsizi Park, part of Tahltan First Nation Territory. The park had been established in 1975 as “a unique wildlife area [requiring] exceptional protection … to ensure that the values associated with wildlife are retained and not permitted to degenerate.” These goals were compromised when the hunting lobby negotiated an amendment to allow trophy hunting.

There was, and still is, big money associated with killing big mammals. In 1979, hunters paid US $10,000 to get a shot at a Stone sheep in Spatsizi. Today, wealthy international hunters pay US $56,500 for a Stone Sheep hunt. Other animals hunted in the park include Mountain caribou, Mountain goat, Black bear, Cougar, Timber wolves, and the Western moose, some bulls sporting 60-inch horns, highly sought after by trophy hunters.

In 1979, we confronted American and Swedish hunters in the park. The Swedes called us Gröntmän, “the Green people.” We managed to disrupt the hunt and were sued by Collingwood. Greenpeace counter-sued after Chechik and others were attacked.

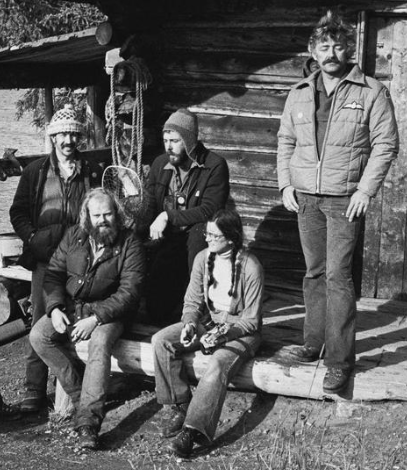

Greenpeace, then and now, supported Indigenous subsistence hunting, a traditional food source. In the 1990s, Kitasoo/Xai’xais First Nation bought out several hunting guides, ending trophy hunting in over 38,000 square kilometres of forest. The Tahtlan First Nation now regulates subsistence hunting in Spatsizi Park, managing the species balance among grazers and carnivores. Here is an image of campaign leader Judy Drake with our activist team: Me on the left, Jim Taylor, Jim Allan, Judy Drake, and pilot Al Johnston, who later went on to fly missions for Greenpeace through the 1980s.