This blog was originally published 7 Nov 2022, and updated 16 Jan 2023.

Five things you should know about Finland’s climate target

Finland made international headlines in 2019, as Sanna Marin, at the age of 34, became the world’s youngest prime minister, and started leading a five-party government with four other women.

Yea, pretty cool!

But it wasn’t just their gender and age. It was their goals too. According to their government programme:

Finland will achieve carbon neutrality by 2035 and aims to be the world’s first fossil-free welfare society.

The carbon neutrality target, along with decadal emission reduction targets, are now enshrined in law. Finland’s new Climate Change Act entered into force in July 2022.

Unfortunately, now the target is in serious doubt: Due to high levels of logging, and forests growing slower, Finland’s carbon sink has collapsed. As a result, Finland’s net emissions are now higher than in 1990. So now what?

Here’s a few things you need to know about that target, and Finland’s action towards it.

1. Finland’s climate target is based on science

Finland’s net zero 2035 goal was set based on analysis by the Finnish Climate Change Panel, an independent, government-appointed advisory council consisting of top-level Finnish scholars.

The target has often been called the most ambitious in the world, and much stronger than that of the EU’s, but actually, that isn’t quite the case. Finland had a relatively big sink to start with, and was therefore assumed to reach net zero earlier than the EU as a whole, simply by cutting it’s emissions while maintaining its carbon sink at the historical level (1990-2018).

Looking at the actual emission reductions, Denmark, Germany and the UK, for example, have stronger 2030 emission reduction targets than Finland (-60 %), compared to 1990 levels.

Despite often being called a “carbon neutrality target”, the target actually covers all greenhouse gas emissions, not just carbon (CO2).

2. Strong climate action was demanded by the people

The government adopted a stronger climate target because that’s what we Finns wanted. The launch of the IPCC 1.5°C science report in 2018 catalysed a massive new wave of climate awakening in Finland, leading to several mass demonstrations and school strikes, and to climate becoming the number one election topic in the April 2019 general election. As a result, climate action took a central role in the government programme, and Finland’s climate neutrality target was advanced by a decade, from 2045 to 2035.

A poll conducted by the Confederation of Finnish Industries (EK) found that 63 % of Finns supported the government’s carbon neutrality 2035 goal while only 13 % opposed it. This was in alignment with two other polls on climate, the Climate Barometer and Science Barometer, which found that a clear majority of Finns supported strong climate action.

3. The goal is supported by business and workers alike

Strong climate targets are good for business, as they provide long-term certainty for investments. This is the view of Finnish business and industries who have endorsed the new, stronger climate goals and conducted their own sectoral roadmap exercises to reach them.

Trade unions have supported the target too. In fact, the video below, illustrating leaders of business, workers, municipalities, science, and NGOs (i.e. key players of Finland’s climate team) convening a message to Prime Minister Sanna Marin (captain of the climate team) in February 2020, is just one of many examples demonstrating the broad societal support for the goal.

4. Some sectors are doing fine, others less so

Now, over three years after the adoption of the target, implementation is ongoing. In sectors covered by EU emission trading things are progressing well. Once the EU, too, updated its climate targets, carbon prices finally started reaching levels that catalyse change. Finland’s energy emissions (power & heat) are falling faster than anticipated, having already halved in a decade on their way to full decarbonisation during the 2030s. (This, by the way, assumes bioenergy is emission free, which it actually isn’t.)

However agriculture and transport emissions are not on track. Agriculture emissions haven’t seen a significant change in 2000s, while transport emissions are declining but not yet fast enough.

5. But now there’s a real problem – net sink collapsed

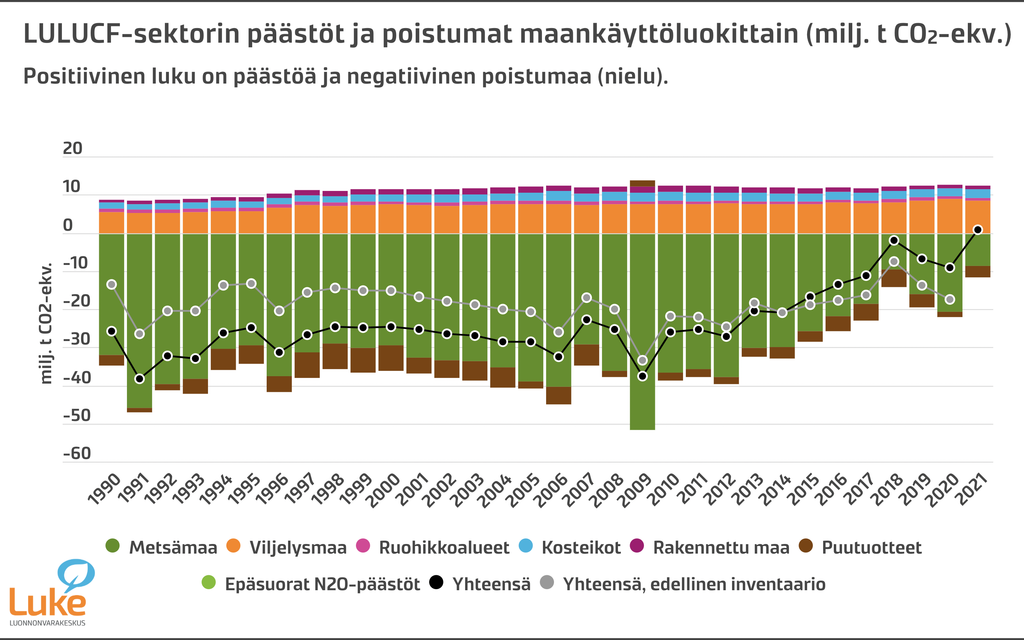

Finland’s land use sector, such as forests and fields, has been a relatively large sink. But in 2021 the land use sector turned for the first time from a carbon sink into a source of emissions, according to official data. The large harvesting volumes and slower forest growth are assumed to be the main reasons for this.

While the size of sink can vary annually, this is a serious warning sign as Finland’s carbon neutrality by 2035 depends on the country’s ability to both reduce emissions and maintain or increase our sinks at the same time. Overall, Finland’s net sink has been on a decreasing trend for the last 10 years, with forest land (metsämaa) being less than a fourth of the level it was in 2012.

Finnish Climate Change Panel, as well as the state research center Finnish Environment Institute have expressed their deep concern about the situation, urging the government to adopt a rescue package for carbon sinks at the latest in autumn 2022. Yet, so far corrective action by the government has been insufficient, and mixed signals have been sent, as Antti Kurvinen, Minister of Agriculture and Forestry has stated that “logging can definitely increase” still.

Greenpeace and Finnish Association for Nature Conservation consider government inaction to be illegal in light of Finland’s Climate Act. The organisations have, therefore, submitted an administrative appeal to the Supreme Administrative Court in November 2022. This became the first climate litigation case in Finland.

In conclusion…

Finland has a science-based climate goal, thanks to people insisting on stronger action. The societal support for the goal has been broad, and progress has been made, but now the collapse of the sink puts the whole target into question.

The situation can still be fixed, but not by assuming it will fix itself. It will require strong political leadership.

We Finns have made a commitment to do our part in fighting the climate emergency. And now we must turn the words into action, with the level of credibility the situation requires.