The European Commission is expected to publish its proposal for a long-term EU strategy on climate change on Wednesday, 28 November. This proposal will set the stage for negotiations between European governments about how much the EU should reduce its greenhouse gas emissions and what action it should take to make sure it achieves these targets. The IPCC’s recent report says the next 12 years are critical. If action is insufficient now, it will likely be impossible to make up for the deficit later.

Climate change is already here

The world’s temperatures have already increased by about 1°C and Europe has already started to feel the impact. The summer of 2018 saw a major heatwave in western Europe, with temperature records broken in several EU countries, including Germany, Spain, Belgium, Sweden, Portugal, Denmark and Finland. Unprecedented fires raged inside the Arctic Circle, while many countries experienced drought.

Farmers across Europe lost more than 12% of their cereal crops this year, with an inevitable impact on the prices of basic foods like bread and pasta. Meanwhile, nuclear power plants were forced to shut down completely or partially in five EU countries, because the water needed to cool the reactors was too hot.

Greenpeace EU climate and energy policy director Tara Connolly said: “Climate change is a fire that has already killed many and is quickly getting out of our control. We need immediate and radical action to put out the flames. The Commission must deliver a climate plan for Europe that meets the scale of the challenge. The EU needs to be carbon-neutral by 2040 to avoid the worst impacts of climate change, which are literally a matter of life and death for millions around the world.

How to avoid climate chaos (and build a better Europe)

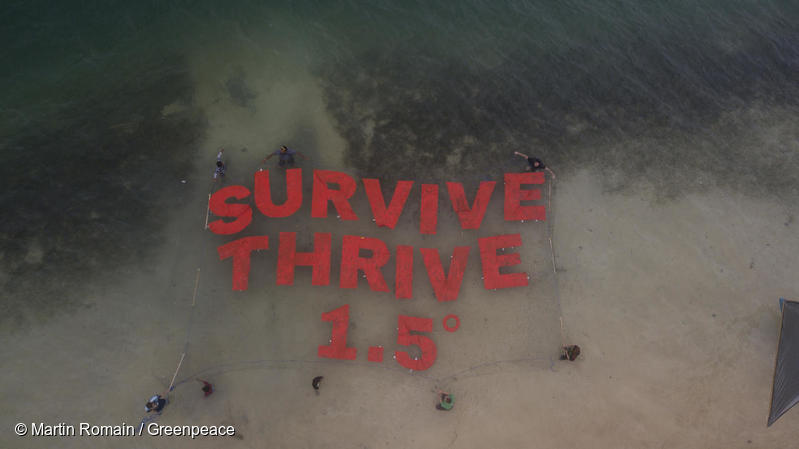

The EU claims to be a climate leader. To make up for its historic emissions, estimated at 25% of all emissions since 1850, and to fulfil the leadership role it claims to have, the EU must aim to keep global temperature increase to 1.5°C. This means its long-term climate strategy must include a commitment to full decarbonisation by 2040. The EU’s 2030 targets must also reflect the findings of the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) special report on 1.5°C, which shows the next decade is critical.

Under the Paris climate agreement, every country must confirm or increase its 2030 climate targets by 2020. The EU is the first major political power to officially start the process of debating higher climate targets since the Paris climate agreement. It must play its part and encourage other countries to increase their climate targets in line with what’s needed to keep global warming to 1.5°C.

The EU’s current 2030 and 2050 climate and energy targets, based on keeping global warming to just under 2°C, are to cut greenhouse gas emissions by at least 40% by 2030 (based on 1990 levels), and by 80 to 95% by 2050. Given the latest IPCC report, these targets are clearly insufficient to avoid the worst effects of climate change and fall below what is necessary for the EU to meet its obligations under the Paris climate agreement.

Just as a failure to address climate change threatens people’s lives and livelihoods, so greater climate action can help improve public health and economic opportunities. For European climate action to reach the required scale, European industry and lifestyles will have to radically change. To be credible and politically feasible, all climate visions will have to take into account the workers and communities affected, and ensure the transition in sectors like energy and agriculture is properly planned and just. Inclusive climate action offers the potential for new green jobs and other benefits, such as better public health through better air quality, more liveable cities as public transport and mobility improve, cleaner water and more secure food supplies.

What is the Commission’s plan to tackle climate change?

The Commission is expected to set out a vision for a zero emission Europe and will lay out eight scenarios to level off emissions in the EU. The first five scenarios would deliver 80% emission cuts by 2050, the sixth would deliver 90% emission cuts by 2050 and the seventh and eighth scenarios would deliver 95% emission cuts by 2050 plus 5% of so-called negative emissions i.e. net zero emissions by 2050.

Based on a leaked draft of a technical background paper, it seems all of the pathways suggested by the Commission fail to take the IPCC report on 1.5°C into account. None of the scenarios propose that the EU fully decarbonise by 2040, as would be required. Almost all scenarios fail to propose a significant increase in the EU’s 2030 climate target, while the IPCC clearly states that emission cuts between now and 2030 are what will make or break the response to climate change. This approach would also leave the bloc with a mammoth task to cut emissions between 2030 and 2050.

What scientists say is necessary

In October, the IPCC published a special report on the impact of 1.5°C of global warming. The report shows that 2°C of warming would be significantly worse than 1.5°C. For example, 5 million additional people would find their homes underwater, and the probability of extreme and destructive weather events like floods, droughts, storms and heatwaves would be much higher in a 2°C world (EM Fischer & R Knutti, 2015 & C.-F. Schleussner et al, 2016).

The IPCC report says that global CO₂ emissions must be halved by 2030 before falling to net zero by 2050 at the latest, if the world is to limit global temperature rise to 1.5°C. Currently, global temperatures are expected to reach at least 3°C, exceeding 1.5°C between 2030 and 2052, if emissions continue at current rates. According to the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP), emissions would have to be cut by 19 gigatons (Gt) of CO₂ by 2030 to meet the target; that’s over four times the annual emissions of the EU.

According to the IPCC report, global coal consumption would need to be cut by at least two thirds by 2030 and fall to almost zero in electricity production by 2050. Renewables would supply 70-85% of electricity in 2050, with trends showing even higher potential. Oil and gas use will need to decline rapidly too. A pathway that does not rely on CO₂ removal technologies would see oil declining by 37% below 2010 levels by 2030.

Importantly, natural climate solutions such as forest protection and reforestation have the potential to provide over a third of the cost-effective CO₂ mitigation needed up to 2030 for a 2°C target, implying high potential for 1.5 degrees too.

Path to a deal and next steps

After the launch, the European Commission will present its draft strategy at a high-level political event at the global climate conference (COP 24) in Katowice, Poland, on 4 December.

A final agreement by EU governments is expected in 2019. At the moment, the timing for these discussions has not been formalised. Some expect the strategy to be endorsed in May 2019, during a summit on the future of Europe in Sibiu, Romania, while others believe the end of 2019 is more likely, given the European parliament elections and the appointment of a new European Commission in the second half of 2019.

On 9 October 2018, 15 European environment ministers called on the EU to increase its targets to cut carbon emissions in line with the recommendations of the IPCC’s report. During the October summit, EU leaders recognised the need for more action to address climate change. The most progressive countries include Denmark, Finland, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain and Sweden. While Poland and Hungary are the most vocal opponents of more EU climate action, the biggest doubt is over the position of Germany, which is currently debating a national coal phase out.

On 25 October, the European Parliament also called on the Commission to back the EU’s full decarbonisation by 2050 at the latest. The Parliament also called for the EU’s 2030 climate target to be increased to at least 55%. It still remains to be seen what role the Parliament will play in the approval of the EU’s long-term climate strategy.

The EU must agree on its new 2030 climate target ahead of a global deadline for all countries to restate or increase their 2030 climate target or nationally determined contribution (NDC) in time for the global climate conference in 2020 (COP 26). However, in order to have any influence on other countries, the EU must make a deal as early as possible in 2019.

Upcoming reports and useful links

On 27 November the UN Environment Programme will publish its 2018 Emissions Gap Report at: https://www.unenvironment.org/resources/emissions-gap-report-2018

On 29 November the Lancet Countdown, a global research project into the public health impacts of climate change, will publish its 2018 report on 29 November at: http://www.lancetcountdown.org

On 29 November the World Meteorological Organisation will release its State of the Climate report at http://www.wmo.int.

Contacts

Tara Connolly – Greenpeace EU climate and energy policy director: +32 (0)477 79 04 16, [email protected]

Laura Ullmann – Greenpeace EU communications officer: +32 (0)476 988 584, [email protected]

For breaking news and comment on EU affairs: www.twitter.com/GreenpeaceEU

Greenpeace is an independent global campaigning organisation that acts to change attitudes and behaviour, to protect and conserve the environment and to promote peace. Greenpeace does not accept donations from governments, the EU, businesses or political parties.