This year marks the 10th anniversary of the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster on March 11 (also called 3-11). We invited three campaigners from our Hong Kong, Seoul and Tokyo offices in East Asia to talk to you about their regional collaboration over the years on the Fukushima nuclear campaign and why it still matters now.

Q: What’s been your role in the Fukushima campaign?

Kazue Suzuki, Climate and Energy Campaigner from Tokyo office: I started to get involved with the Fukushima campaign full-time in May 2011. The Japanese government was pushing to restart schools in Fukushima but so many parents were concerned about the dangers of radioactive contamination. We began campaigning and our demand was that they evacuate children and pregnant women outside the evacuation area where radiation readings were still many times higher than safe levels.

Mari Chang, Climate and Energy Campaigner from Seoul office: I’m the project leader of the Seoul office’s nuclear campaign. I started off overseeing the coal financing campaign when I first joined Greenpeace, but since I’m really interested in the nuclear campaign, later I worked on both.

It’s been important for us to communicate with all offices in Greenpeace East Asia, including our Tokyo office on campaign outputs to achieve synergy. It’s also important to work with experts so that we are conveying science-based facts and genuine knowledge. Also, this campaign is not just a public-oriented campaign; we’ve also been focused on higher-level policy makers in our own countries too and I’ve taken on significant roles in lobbying and political engagement with the Korean government.

I’ve been in Greenpeace for only three years now but I’m very thankful to Greenpeace for being there. Greenpeace was one of the first to be there on the ground at the accident site, right after 3-11. I’m very proud of this fact and also all the survey work that has been done over the last 10 years. We have been able to rapidly provide the truth on the ground and that has kept Greenpeace visible in this issue and has also prevented the Japanese government from hiding the real situation.

Ray Lei, Head of the Research Unit from Hong Kong office: For me, I’ve been more involved on the field frontlines of the Fukushima campaign. I was one of the Radiation Protection Advisers and was mainly responsible for monitoring radiation levels on the ground and personnel protection in the field at Fukushima. I was there for the first time in August 2011 after the nuclear disaster happened.

Coincidentally, in November 2010 I had studied and got a certificate in how to safely work in radioactive environments.

I’ve been back to Fukushima several times for field training and monitoring work; over these 10 years I’ve witnessed decontamination workers busy doing decontamination work in forests, on the roads and in small streets. I’ve seen countless piles of storage bags containing radioactive waste along roads and been transported. Some families have had to uproot their whole lives and leave their home behind.

I’ve also witnessed a pattern of recontamination in streams and rivers. That’s why Greenpeace is advocating that we need to keep monitoring to make sure it’s safe for people to go back.

While I was there, I felt uncertainty, something unknown. We all had our personal alert pagers to tell us the radiation doses we were exposed to, it was a surreal experience. I had no idea when I did the radiation training that in just a few months I would be in a real battlefield with dangerous radioactive contamination. This experience exposed myself in a constant radiation contaminated environment that one could not see, smell and taste. During field monitoring, we had personal protection equipment and dose checked everyday, but there are still many residents living there who have to endure it for a much much longer time in daily life with limited means to protect themselves.

What’s your vision for the Fukushima campaign?

Kazue: People forget, so we should keep reminding them what happened in Fukushima. The Japanese government wants to use nuclear power to reduce carbon emissions to tackle the climate crisis, but that’s not the answer. We should keep pushing for 100% renewable energy. There is no guarantee that you can prevent the risks with nuclear power plants, the only way is to not have them.

People from Fukushima repeatedly say they don’t want any other people to go through what they did.

Ray: I wish Fukushima residents can return to their homeland, to their houses and villages safely. That’s my vision for this campaign. I was shocked and speechless when I first went to Fukushima, the city was almost empty. In some of the restricted areas – about 20 to 30 km from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant – it felt like time had stopped.

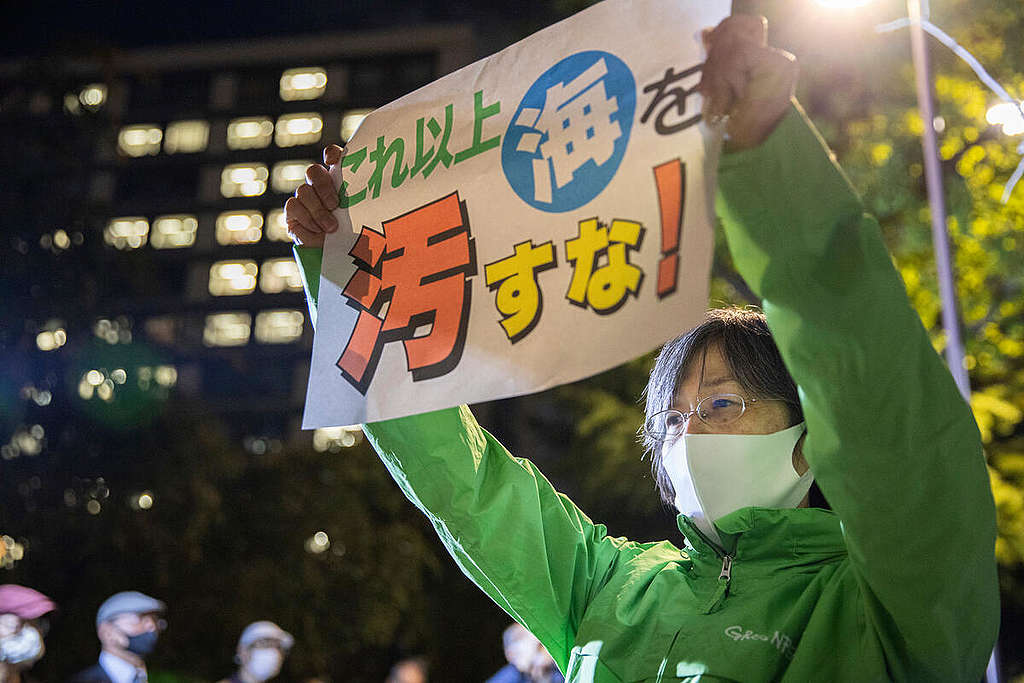

Mari: I’d like to add another aspect from the Korean point of view. We think that stopping the release of contaminated water [used to prevent the damaged nuclear cores from overheating] from Fukushima is a priority. If the Japanese government doesn’t solve this problem in the next five years it can easily worsen the situation regarding the decommissioning plan and consequently to the whole Fukushima prefecture.

Greenpeace has consistently urged that the contaminated water should be treated properly until the radioactivity falls to safe levels that are not hazardous to humans.

What memories do you have of the Fukushima campaign?

Mari: I just want to share one thing. In 2019, I was in Fukushima for almost a month; it was my first radiation survey. I knew it could be dangerous, but the one thing that was very clear to me was that you cannot work on the Fukushima campaign without any experience in Fukushima. On my last day, I was in Tokyo waiting for my flight home because it had been delayed by Typhoon Hagibis. In the morning, I don’t know why, I suddenly started crying for a few hours as I remembered all those people in Fukushima whose lives had been impacted by the disaster. I don’t think I will ever forget that morning.

Ray: The first time I went to Fukushima, there were more than 20 colleagues with me and I was so amazed that in a very short period of time we came up with a plan about what we needed to do, that’s a very good example of our collaboration and the commitment our colleagues have to the nuclear campaign and the Fukushima work. I want to thank Kazue and Mari for our latest field work together in 2019 and for coming up with some really thrilling video footage that showed exactly what was still happening in Fukushima – the contamination and the situation for the people living there.

How do you keep the collaboration going during the pandemic?

Mari: I feel that Covid hasn’t really stopped our work. Our colleagues in Japan still sent a team to Fukushima last year, and that’s how we were able to still release two reports on the campaign. In the Seoul office, we brainstormed how to use social networks. Although Covid has caused many difficulties, it has also driven how we think about campaigning under such changed circumstances, and how to convert the crisis into new opportunities, too.

Kazue: Well, even before Covid, Mari, Ray and I would talk online, and so I think our collaboration has not suffered so much from Covid.

Ray: Amid all this uncertainty and the reality that we cannot meet face to face, we have still managed to find ways to put our offline activities online. We have collaborated remotely to come up with these new reports to address issues such as the contaminated water to be discharged into the Pacific Ocean. We work as a team to support each other .

Why did you join Greenpeace in the first place?

Kazue: In 1991 there was a war between Iraq and the United States. The Japanese government supported the war, using taxpayers’ money—my money—on the war and that made me very angry. I wanted to stop it but I didn’t know how. There was no internet back then so I went to the phone book and looked for any organization with “peace” in the name. I didn’t find Greenpeace, but I did find another organization and went to one of their meetings and it was there that I met people from Greenpeace.

I thought what Greenpeace was doing was great because they were not just demonstrating against war; they were arguing that we shouldn’t be fighting over oil. If we have the money to go to war then we have the money to invest in renewable resources instead. I thought I have to work for this organization because it goes to the root cause of the war. And that’s my story!

Mari: You know this question just made me travel way back into the past! I had never really thought about working for Greenpeace because in the past I was more into local grassroots movements. But two things changed my mind.

First, the Sewol ferry disaster in Korea where more than 300 people died when the Sewol passenger ferry sank in April 2014. Many of those who died were school students, and at the time I blamed the government because they hadn’t tried hard enough to save them. And that reminded me of what had happened in Fukushima. And when I was searching for an organization to work for, I saw that Greenpeace had been campaigning for almost half a century and making meaningful progress and famous for its nuclear phase out campaign. I joined Greenpeace because I want to take part in creating solutions and impacts.

Ray: I have been with this organization for 14 years. Before I joined Greenpeace, I was part of the commercial world. At one point, I thought I needed to rethink my career and find something more meaningful. I looked for that job and Greenpeace was what I found.

I’ve been involved in many kinds of research investigations for all different campaigns. I’ve worked in dangerous situations, for example I was chased by factory security guards when we attempted to find their effluent discharge pipes doing water sampling work among other hazards and adverse facing in the fieldwork. Anything can happen! It’s all part of the job.

I believe that Greenpeace campaigns really make positive change. I feel privileged to work in this organization for a better world.

What would you like to say to our supporters?

Ray: Nuclear power is a global issue. I would ask our supporters, wherever they are from, to sign petitions to demand with us that Japan does not discharge contaminated wastewater into the Pacific Ocean. I think it’s also important for us to ask the Japanese government to ensure that before reopening restricted areas that they are also properly safe for people to go back home.

Mari: I agree with Ray. Nuclear phase out campaigns are needed in many countries like South Korea that are running a bunch of reactors even under so many challenges. It is not a problem only for Japan; it’s a campaign for all places that have nuclear power. So, as well as working on the Fukushima radioactive water project, we also communicate to the public about the dangers of nuclear accidents happening here in Korea, too. It’s important to emphasize that we have a clear and safe alternative to nuclear power and that we should transform to 100% renewable energy as soon as possible.

I also think it’s really important to communicate to our supporters and donors that all of our hard work became possible because of their continued support, financially and non-financially.

Kazue: I would invite people to look into who is funding nuclear power plants. For example, the Tokyo government is a shareholder of Tepco [Fukushima plants’ operator]. Check if your bank also does. I don’t think people realize that Toshiba, Mitsubishi and Hitachi all have connections with nuclear power. We can tell them we won’t buy their products if they continue to support the nuclear industry. We can do lots of things.

In environmental activism we have a saying that means something like: “I cannot do it, but we can do it.” So as an individual, I cannot do it alone, but collectively we can do it. And that goes for how Greenpeace does its work in East Asia and globally too.

I’m really grateful to all our supporters; they inspire me to be resilient and persistent because they are supporting our work.

I believe you have to be part of something because as I said, you cannot do it by yourself. You should be part of something you feel strongly about and if it’s Greenpeace, then I’m very happy that we will work together for a safer planet!