It has been more than 20 years since the shocking documentary L’Erreur Boréale was released to the public, shaking up Quebec while rattling the cages of decision-makers and Big Forestry along the way. It was the trigger for a series of reflections on our relationship with the boreal forest and how we can achieve a new forest management regime.

But how have we evolved since these warnings and the recommendations were made? More importantly, where are we today? How is the boreal forest in Quebec doing?

Barely five months ago, the world’s decision-makers (during COP15) signed an historic agreement in Montreal with the goal of reversing the ecological crisis and the loss of biodiversity and our ecosystems.

It’s time to take the pulse on the extent to which all these words are turning into action.

A history of failed biodiversity targets ?

Since Quebec first joined the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in 1992, it has systematically failed to meet its international biodiversity commitments. Since 2010, Quebec has barely moved the needle: increasing new protected areas by just 2.5%. In 2016, in a rare commentary, the Executive Secretary of the CBD, M. Dias, nudged Quebec to go further, stating, “Quebec has a unique biodiversity, including some of the last watersheds and intact forests on the planet. Achieving the Aichi Targets is a necessary step to preserve this heritage for future generations.”

Months prior to the 2020 deadline, the province was still lagging far behind its objectives, until mid-December when it declared it had reached its Aichi Biodiversity Targets. To much surprise, Quebec jumped from 10.7% to 17% land-based protected areas, and from 1.3% to 10.4 % marine protected areas. This is a massive leap! But the devil is always in the details… Unfortunately, Quebec failed to understand the assignment.

Not only did Quebec not actually achieve 17% protected areas (but 16.7%), as was later uncovered on its registry, but Quebec failed to respect the science, CBD objectives, and guidelines by concentrating much of the protected areas in a couple of regions. The real target is to preserve biodiversity across the whole province in Quebec. With only 9% of protected areas in the southern and most populous part of the province (below the 49th parallel), we cannot say that these areas are really representative of the various ecosystems of the region. Protection needs to consider biodiversity hotspots, factor in recovery of endangered species, and should be equitable in terms of providing muchneeded access for people and wildlife. Unfortunately, connections between protected areas – sometimes referred to as green corridors – is also lacking.

The protected areas fiasco in Southern Quebec

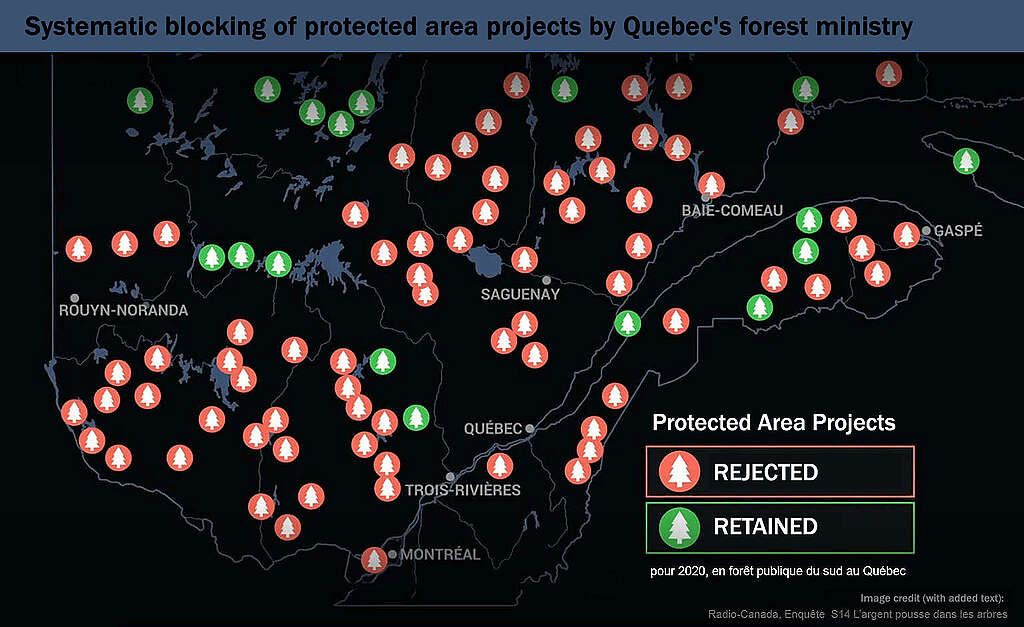

Quebec struggled at the last minute to meet its protected areas target, but this could easily have been avoided. In southern Quebec, 83 conservation projects that were approved by local communities through a multi-stakeholder process have been waiting for the government’s approval for over a decade. To the astonishment and outrage of many, all projects were excluded from the 17% protected areas announced in 2020. Areas selected were further north, beyond the limits of forestry operations and away from highly populated areas. Protection in the North, on Cree land, was very important and something to celebrate, but Quebec could have easily gone beyond the 17% goal… Why didn’t it? The answer was clear: where the logging industry has interests, proposed protected areas are systematically blocked.

In the fall of 2020, civil society and environmentalist groups, including Greenpeace, denounced a clear desire by the Quebec’s Ministry of Forests, Wildlife and Parks to curtail conservation efforts. A 2018 internal document from the ministry (MFFP) unveiled a strategy aimed at curbing the creation of protected areas in 11 administrative regions of the province. Despite an exhaustive study showing the multiple benefits of forest protection for the region, and clear public buy-in, conservation proposals such as the one for Mount Kaaikop have been given the cold shoulder by the government.

Quebec recently changed what it means for an area to achieve protected status, making more logging possible. But opening the door to logging in protected areas is not new. In recent years, the forest minister also called for more logging of old-growth forests in the name of climate change, and their ministry plans to double lumber output from the forest over the next 60 years. It is clear that private interests have a lot of power in the Quebec government, and it’s damaging public health and the natural environment.

The Caribou Crisis: A shining example

Woodland caribou are a symbol of the threats facing wildlife in Quebec, the lack of political will to address the biodiversity crisis, and the forest industry’s destructive practices. As an umbrella species, the caribou is a barometer for how well the ecosystem in the boreal forest is doing.

One generation of caribou has passed since Quebec added it to its species at risk list in 2005. In this time, 30% of woodland caribou populations across the country have declined. Most of the herds are seeing their old-growth boreal forest habitats highly degraded. And where there is less than 35% disturbance, caribou have a 60% chance of survival.

Despite this, Quebec still has not published a recovery strategy. In fact, it has postponed it twice already. The industry lobby is exercising every tactic in the tobacco industry’s playbook to keep logging away. As a result, the Quebec government has claimed caribou recovery is too expensive. It has even proposed sending wild caribou to the zoo (in the case of the Val d’Or herd), allowed logging permits in protected areas, and commissioned endless reports and consultations without concrete action.

In spring 2022, the federal government threatened Quebec with imposing protection through an emergency order if it failed to show proof of caribou recovery efforts. Both governments seem to have negotiated some understanding moving forward. But as Quebec’s latest commission on caribou concluded, no herd should be abandoned (as proposed in one of the scenarios) and concrete action is needed now in conjunction with Indigenous Peoples.

The lack of Indigenous inclusion in forest management

The Quebec government continuously struggles to consult with impacted First Nations, and this is representative of the systemic racism that runs deep within the government, its policies and programs. A glaring example of this is when the minister of forests, wildlife and parks scapegoats Indigenous communities, in their right to hunt, for his ministry’s failures in addressing the caribou crisis.

The latest commission on caribou was described by the Assembly of First Nations Quebec-Labrador as “a ploy that legitimizes the Government of Quebec’s inaction in protecting and restoring caribou and their habitat” while denouncing Quebec’s lack of consultations with First Nations and the denial of their expertise. Lac Simon First Nation has been proposing conservation measures for the Val d’Or caribou herd for the past 30 years to no avail, and recently launched a petition with Greenpeace calling for a logging moratorium. The Innus First Nations of Essipit and Mashteuiash on their end decided to bring Quebec to court over the lack of consultation around caribou, which is considered an infringement on their rights.

Path Forward: First Nation stewardship in the boreal forest

Biodiversity is vital to ecosystem health and community resilience. If we want to keep reaping the benefits of the rich ecosystems in Quebec and Canada, we need to act quickly to bring back endangered species. Quebec must lead by example, starting by holding Nation to Nation talks and respecting and prioritizing Indigenous rights and conservation leadership.

Discussion

I'm interested to know how many logging companies are spraying forests with Glyphosate. The not for profit organization I work with is putting on an on-line event about Industrial Logging and its effect on climate change on Tues. June 27 at 7 pm EST. Please register here: https://us02web.zoom.us/meeting/register/tZMtdu2rpzMjGta8xFNkLBDnJhNbAiVxvdmx I'm happy to send more info if you're interested. Guest speaker is Michael Polanyi from Nature Canada.