This year, we have a chance to witness the biggest global conservation effort in history. If world governments secure a strong Global Ocean Treaty under the UN, we could start down a new path of recovery and preservation of marine biodiversity. We are at a point where we must go beyond focusing on one ecosystem, one ocean, or one species. With too many species to count currently in survival mode, we need action that mirrors the scale of the problem. And this problem isn’t just occurring in the oceans — it’s across the entire planet.

What is biodiversity?

Biodiversity (short for biological diversity) is the variety of all living species on Earth. Plants, fungi, animals, bacteria; from genes to communities to ecosystems, biodiversity is the beautiful rainbow of life all around us. Each species has a unique role to play on this planet, and preserving biodiversity helps to ensure that ecosystems and food chains can remain intact and function as they have evolved. While the question “why is biodiversity important” is regularly answered from the perspective of what it can do for humans, each species has value in its own right.

The biodiversity crisis

The biodiversity crisis is a crisis of what we call “Nature”—the living planet beyond the human-centred world we’ve built (but one that humans are very much part of, for better or for worse). In recent history, that human-Nature relationship has too often been toxic. At least one million other beings we share this planet with are at risk of becoming part of the sixth mass extinction. The last extinction event (not human caused) occurred 65 million years ago. In such a relatively short time period, humans have caused this crisis—and global governments are now fumbling to get a handle on it.

But not everyone is shocked that the future of biodiversity is in question. Indigenous peoples and scientists have been sounding the alarm that our relationship with Nature is out of balance. Without urgent action on the climate crisis and serious efforts to curb our extractive, polluting and destructive ways, it’s going to be bad news for us all. It’s hard not to feel the weight of this and worry for future generations and the flora and fauna we all love.

How did we get here?

The destruction of nature and the oppression of nature stewards is rooted in colonialism and continues to be perpetuated by those enduring structures and mindsets. The evolution of our current take-take-take-make-waste capitalist system that is fuelled by endless exploitation on the backs of BIPOC communities has meant that Nature and people are too often seen as dispensable.

Now, Nature as we know it is vanishing. And yet we are all completely dependent on healthy ecosystems for our survival—if the bees and sardines go, we’re not far behind. It’s the same root causes, overarching threats, systems and destructive mindsets driving this crisis on land and at sea. Just like shared threats, the path to restoring Nature whether on land or in the oceans has shared solutions. We need to bring it all together; to start looking at protecting the diversity of life on this planet in all its forms. We want to protect at least 30 per cent of our planet by 2030 and half by 2050 — an achievable goal if we start now.

Here and around the world people are doing so much to respect and protect Nature. This momentum provides hope for a green and just recovery for our planet and all its beings. We need to change the conversation about our future and who is involved in creating it.

Decolonizing nature: towards Just Protection

Colonizers and settlers disrupted the relationship between Indigenous peoples and Nature across this land and along the coasts. Justice for Nature starts with justice for Indigenous people, and conservation of nature starts with Indigenous-led conservation. Inuit, Metis and First Nations people across so-called Canada occupy land and marine-based territories, including ice. In the Arctic, for example, Inuit territory extends beyond definitions of jurisdictional borders and boundaries, and, as such, environmental governance and management decisions must not only consider Indigenous rights and title, but must centre it.

With many of the proposed protected areas or biodiversity hot spots taking place on unceded territory, protection initiatives must not reinforce colonial approaches but must instead be a truly collaborative, Indigenous-led process. For people to feel invested in Nature’s future, they need to feel part of that future. We all need to work to create more inclusive and diverse conversations about nature and accessible natural spaces.

What’s ahead

In the coming months, you’ll be seeing more from us about the types of federal policy initiatives we believe are needed to begin to reverse the decline of ailing species and restore biodiversity in so-called Canada and globally. Through their federal mandate letters, Ministers Guilbeault and Murray have both been charged with ensuring “Canada meets its goals to conserve 25 per cent of our lands and waters by 2025 and 30 per cent of each by 2030, working to halt and reverse nature loss by 2030 in Canada, achieve a full recovery for nature by 2050 and champion this goal internationally.” The biodiversity and climate crises are inextricably linked. The latest IPCC report reaffirms this connection and the need for concerted and strong action on climate and nature protection by world leaders. We will be holding them to account.

In the meantime, the Canadian government has a chance to live up to its international commitment by helping to secure 30 per cent of the global ocean commons in ocean sanctuaries by 2030 (30×30). Global governments met in March at the UN for what we had hoped would be the final round of negotiations on a Global Ocean Treaty. Unfortunately, the pace of negotiations did not reflect the urgency of the situation in the oceans. A strong Treaty could be a game changer for marine biodiversity and coastal communities, and we need Canada to show leadership when governments convene again later this year. Add your name to the almost 5 million people who want global governments to agree a strong Treaty that can fill legal gaps in high seas governance and allow the creation of a global network of ocean sanctuaries. Currently only 1 per cent of the high seas (areas beyond countries’ jurisdiction) is protected. It’s these kinds of pivotal moments that can yield the urgently needed higher and faster returns for nature.

It’s often said that despite everything, Nature will prevail and we should really be focused on saving our (human) selves. It’s not an either or. When we put aside scientific definitions of biological diversity, species richness and ecosystem health and swap out our anthropocentric lens, we are left with a knowing that all species have intrinsic value worthy of protecting.

Did you know…

…that protecting biodiversity is in Greenpeace’s mission statement? Greenpeace’s goal is to:

“Ensure the ability of the earth to nurture life in all its diversity. That means we want to: protect biodiversity in all its forms; prevent pollution and abuse of the earth’s ocean, land, air and fresh water; end all nuclear threats; and promote peace, global disarmament and non-violence.”

There is so much we can do together to turn things around. If we can protect nature in a way that restores the balance, repairs the human-nature relationship and creates the conditions for adaptation and evolution, we can begin to put the puzzle of life on Earth back together.

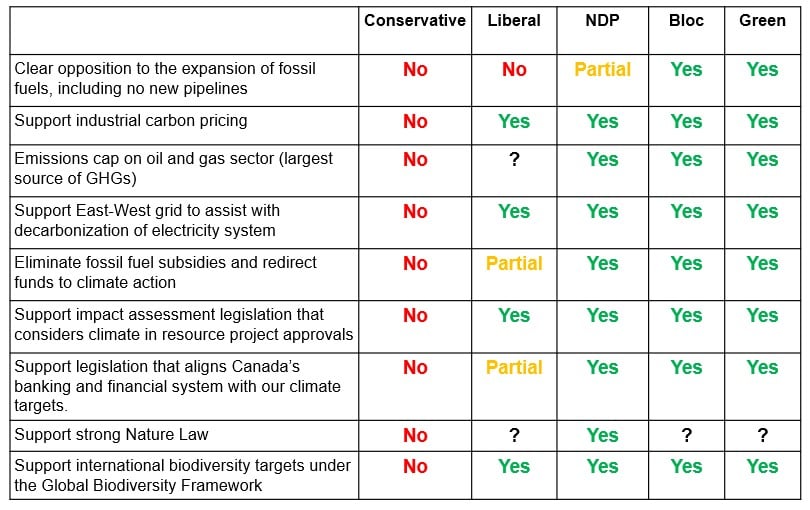

One thing you can do right now: sign our petition calling on Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault to pass a strong Biodiversity Act that respects the inherent rights of Nature and Indigenous sovereignty.