Months into the pandemic, physically and emotionally exhausted from trying to run an organization while taking care of a toddler full-time, there was one topic that really got to me: self-care. It’s hard to describe the feeling I would get when someone would tell me that I should just go for a walk, get some more sleep, take some time ‘just for me’. How such kind, well-intentioned words could generate such a feeling of rage, because of the complete lack of understanding they exposed. And I know it’s not just me — the New York Times recently created a call-in line specifically so that working moms could scream into the phone. Trust me: if we could just chill out a bit, we would. The system and culture we live in just don’t allow it.

Like so many other issues, the pandemic didn’t create the problem, but it’s shone a spotlight by bringing it to such extremes. As Pooja Lakshmin explains, part of what’s been revealed is a societal betrayal of working moms: “While burnout places the blame (and thus the responsibility) on the individual and tells working moms they aren’t resilient enough, betrayal points directly to the broken structures around them.”

But what if things were different? If, as activists, we can imagine an entirely different global energy system, a radically different relationship between humans and nature, an end to exploitative capitalism — then surely we can imagine a world in which spending less time at the (virtual) office, prioritizing personal and family life, and showing up to work refreshed and energized becomes the norm.

This international women’s day, I’m thinking about how rejecting the toxic culture of overwork is a feminist act — and how a completly different vision of working life would empower more women to take on leadership roles, and enrich our organisations with so many more ideas and perspectives.

The price we pay for the toxic culture of overwork

In a toxic culture of overwork, working long hours, being constantly available, and putting family aside to respond to demands are the norm. And I’m sorry to say that this culture is as strong in purpose-driven NGOs like Greenpeace as it is anywhere — after all, how can anyone justify working less hours when their work is advancing human rights, or stopping climate change? As activists at heart, the personal sacrifices we make for our work can become badges of honour, often even the basis of our identities.

But when that toxic culture of overwork collides with a sense of dire urgency around the work itself, the pressure can be crushing. And it shuts a lot of people out. Many people, including women with significant caregiving responsibilities, simply cannot thrive in these work environments without extreme personal sacrifice. When we continue on working this way despite that fact, we devalue these women as people, we devalue their contributions, and we lose out. At the end of the day, it’s just one of the many ways in which many purpose-driven organizations have fooled ourselves into believing that we “can’t afford” to be more inclusive.

As a single mom to a young child, I know first hand how incompatible this kind of work culture is with being a primary caregiver. I’ve been with Greenpeace for a long time, and for many years I just assumed that if I had a child, I would have to leave my job as a campaigner. After all, when I looked around at those in similar roles to mine, I saw almost no women with children. I saw dads, but not moms. There were some exceptions, some amazing women who made it work — but the pressure on them was immense, and eventually, they usually left too. There is no question to me that as an organization and as a movement we have lost and continue to lose brilliant women because of an intolerable and un-inclusive work culture that values an outdated notion of productivity over women’s ideas and contributions.

And what’s worse, it’s not effective anyway. When we buy into the idea that relentless work is what will achieve our goals, we’re fooling ourselves. Doing the most things is not the same as being the most effective. Having the most meetings is not the same as cultivating the most connection. We know these things — and yet, anyone who’s been around the NGO scene long enough knows a lot of people who have experienced severe burnout, knows a lot of people who have suffered serious stress-related health problems, can think of a lot of brilliant minds who left their organizations or the movement because they simply could not continue. (Side question for anyone naming names in their heads right now: how many of those people were women? How many were women of colour?) How is that helping solve the climate crisis?

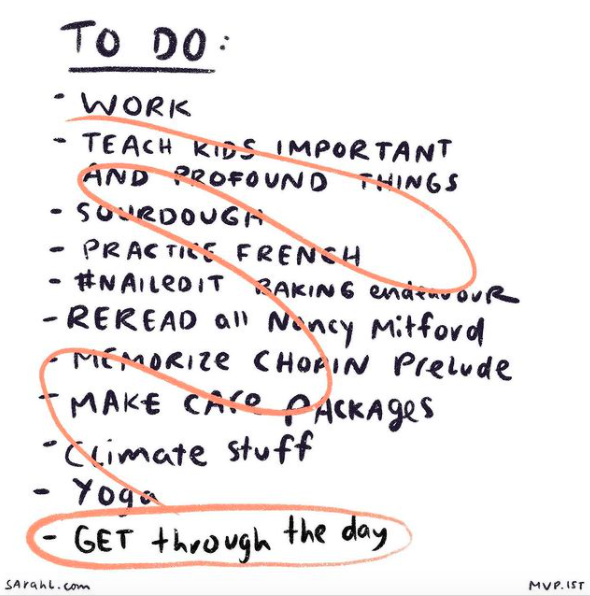

But unlike the pitch we’re given so regularly, the answer to this problem is not self-care or personal wellness — which often ends up as just another thing to add to our ever-expanding to do lists. The fact is that without broader culture change and a tone set from the top, individuals who set firm boundaries and prioritize their lives and their families over their work will very often be punished in one way or another. Certainly, they often won’t be seen as serious candidates for leadership positions.

The pressure to continue on in this way is even more intense for women and BIPOC folks, who need to work harder, prove themselves more, to be seen as smart and serious and legitimate in so many work spaces. I certainly bought into it myself for many years, and I deeply regret the pressure I put on others as a result. And if I’m being honest, I don’t think that I would be in the position I’m in now if I hadn’t pushed myself and my peers beyond our limits for so many years, and sacrificed so much else to do the work. But that’s not what I want for those who come next.

There is another way

That’s one of the reasons why Greenpeace Canada is trying something different: a four day work week. Not a compressed work week in which five days-worth of hours are crammed into four longer days, but a 20% reduction in hours, at full pay. Our assessment ten months in? It’s the best.

Our work is stronger than ever. Our staff feel more valued. They’re healthier and more energized and more creative at work. They don’t feel so much like succeeding at work and being happy and successful at home are in constant, unresolvable tension. The flexibility it affords has allowed more parents to keep working through the pandemic. And as an organization, it feels like we’re doing a better job of living our values by working to create a different world and a different culture than the one that’s been handed down to us.

It’s not perfect, and we still have a long way to go. Our ways of thinking and working are so entrenched, we still have far too many meetings and put far too much pressure on ourselves and our colleagues. Our vision of a truly healthy organizational culture is still an aspiration. It’s understandable, really: our drive to achieve our goals remains as fierce as ever, and we’ve never really seen or experienced another way of doing things.

But we’re creative people who love to envision a different future. So this international women’s day, let’s reimagine work. Let’s create organizations and movements that value people as humans, not just as workers; that welcome the perspectives and contributions of everyone who’s ready to bring them, not just of those with boundless time and a willingness to self-sacrifice. And let’s be joyful as we do our good work.

—————

Who am I? I’m the Executive Director of Greenpeace Canada, and the mom of a sweet and funny three-year old. A long-time Greenpeace activist, I joined the organization for the ‘peace’ and stayed for the ‘green’. I believe that Greenpeace is at heart a values-led organization, and that justice should be an integral part of everything we do.

Discussion

Christie just wanted to say a huge thank you for this bold and courageous move, AND for taking the time to write it down and share the thinking with the world. I have referenced this more than a few times and sent it to other senior leaders. You are a trendsetter and this is the way our advocacy world needs to head. Also, hi! Been a while good to be working with your team again on good stuff.