This year for Christmas, my daughter announced that she wanted a specific unicorn toy that she had seen at one of her friend’s houses and had been pining for ever since. It’s a memorable toy so I can’t blame her: it has a magical light up horn, makes whimsical noises and has several movement sequences that are activated by touch.

As far as unicorns go, this is as real as it gets. But the mass production and consumption of kids toys also has real environmental consequences (and since it has mechanical parts, such toys contribute to the growing e-waste crisis).

So I did what I do every year around the Holidays and jumped onto one of the many platforms that make the secondhand marketplace so accessible in the age of the Internet. A quick search and a few clicks later, I had located the exact item she wanted down the street from me and for a fraction of the price it would have been new. It turned out to be in immaculate condition and the family who had loved this toy previously had even kept the box. But the best part? Batteries were included!

Looking for items secondhand has become second nature to me and began with my journey into low-waste living in 2014, when a group of friends and I launched the Toronto Tool Library. Back before the sharing economy was uberized and transformed into its less palatable cousin, the gig economy, we set out to change attitudes around consumption: do you really need a drill, or do you need a hole in the wall?

We have become accustomed to associating the experience we want or need with the ownership of a thing. This fusion of stuff with experiences leads to the inevitable: every house in your city ends up with a drill sitting in the basement, and each of those drills will only be used for approximately 13 minutes over the duration of their usable lifespan. And then what happens to them?

A report released in the UK estimates that 80% of the stuff we buy, including the plastic packaging it comes in, will end up in landfill, incineration or low quality recycling, often after a very short life. Most of the materials these things are made from will be used only once.

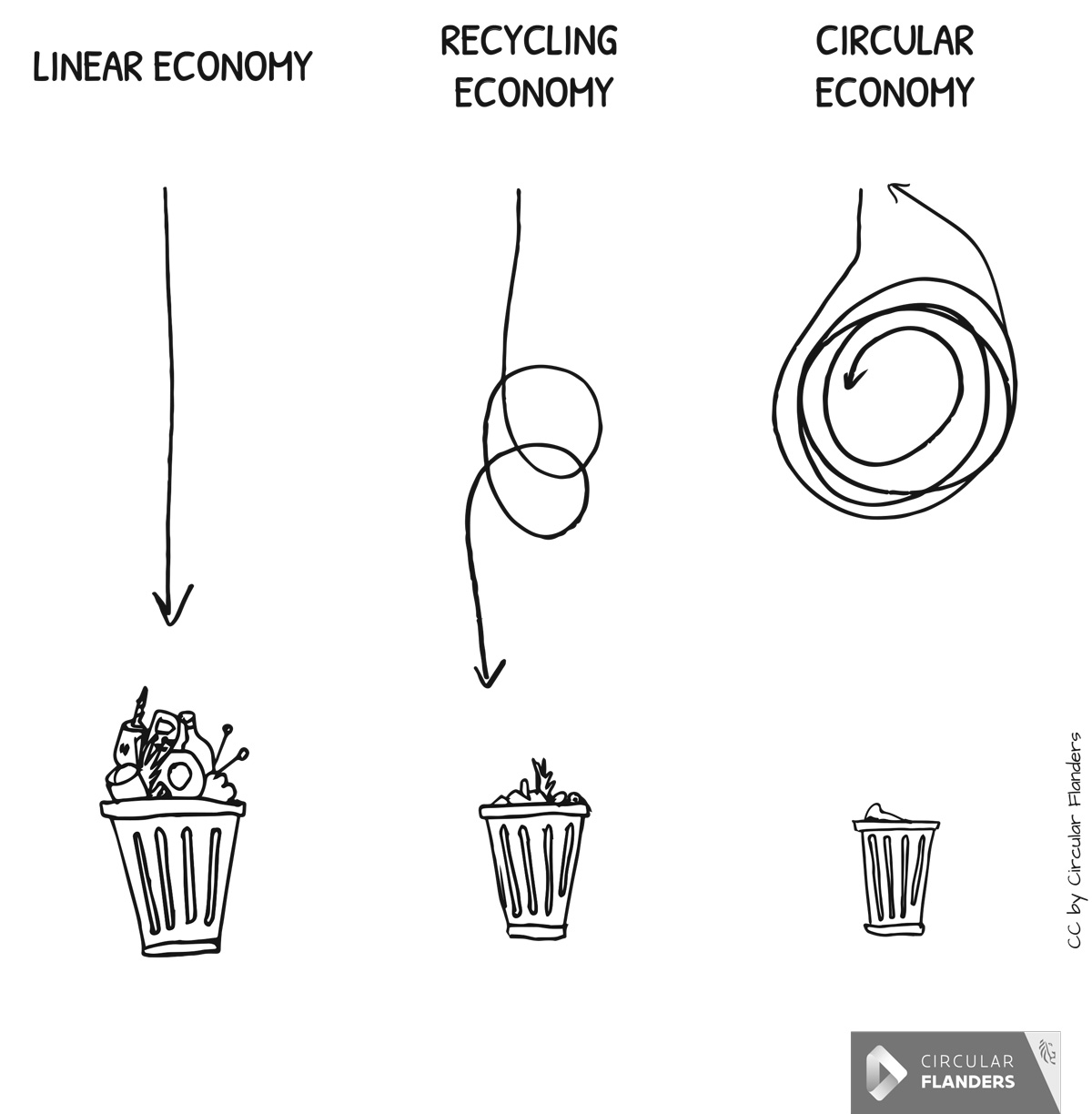

This level of waste is not inevitable, however. It is a design flaw of the take-make-waste linear economic model of resource use and consumption. Materials are taken from nature, turned into something we think we need and then chucked in the bin when we’re finished. Maybe some of the parts get disassembled and reincorporated into new things, but a whole heck of a lot of our unwanted stuff ends up on the shores of developing countries and in the environment. Once the thrill wears off, it’s someone else’s problem, right?

But it’s really everyone’s problem, because when you structure an economy around infinite growth via the consumption of infinitely more stuff on a planet with finite resources, inevitably you are going to slam up against the unforgiving wall of natural limits (what’s that knocking at our collective doors? Hellllllo biodiversity loss, ecosystem collapse and climate change). We can’t go on consuming at the levels we have been if we want a fairer, more equitable and safe planet to live on in the future.

Does that mean we have to tighten our belts and go without? Maybe a little, but probably not as much as we might imagine.

Bending a straight line into a circle

As the report Building a Circular Economy details, eliminating the massive amount of waste our consumption generates requires shifting to a different infrastructure: a shift from a linear economy to what’s known as the circular economy. To work, this would require entirely new business models, facilities, city design and logistics to lower consumption through sophisticated systems of repair, remanufacture and recirculation of products.

In such a system, things are built to last as long as possible with durable design along with the ability to be easily upgraded and repaired. At the end of its life, such a product would be easy to disassemble with as much material as possible reused to create something else.

Like so many positive societal changes, the foundation for the infrastructure that will scale the circular economy is already being built from the bottom up. Repair Cafes are popping up around the world where volunteer ‘fixperts’ help people mend their broken things. Tool Libraries, Libraries of Things and Clothing Libraries empower people to come together and share items as a community. Teaching people to upcycle materials is found in organizations like Boomerang Bags and Creative Reuse Toronto. And repair/reuse malls like Retuna Återbruksgalleria bring all of this together in the world’s first secondhand shopping centre.

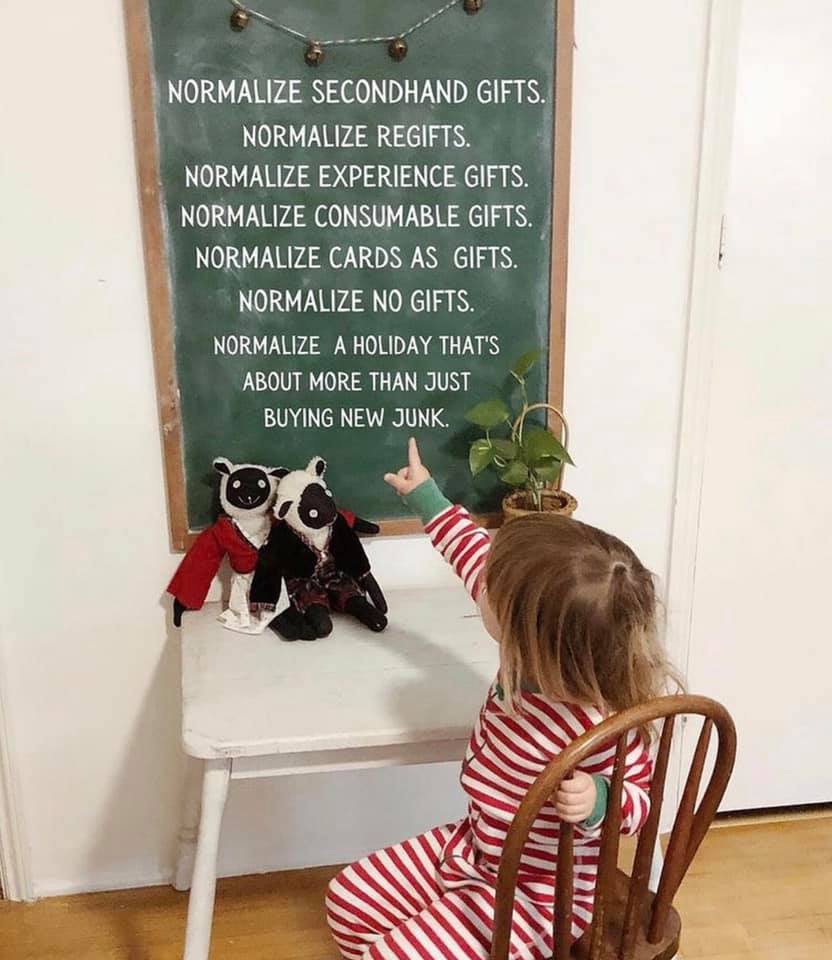

We won’t transform our linear take-make-waste economy into a sustainable circle overnight – putting repair, reuse and recirculation at the heart of our economic system will take government support and intervention to bend the linear line of consumption into a true circle. But there is something we can all do right now to shift the cultural mindset around stuff: we can normalize giving secondhand gifts.

“The next government needs to kick-start a resource revolution and change the system, starting with the infrastructure that enables a circular economy to thrive.” – Phil Purnell, Professor of Materials and Structures

The preloved market isn’t what it used to be – it’s better.

Buying preloved gifts is losing the ick factor associated with the term “regifting” popularized by a 1995 episode of Seinfeld where an unwanted label maker is passed from person to person.

Thanks to the Internet, the world of secondhand goods has exploded into a convenient, easy-to-use network of search bars and location specificity. Online platforms like Bunz Trading Zone and the Freecycle Network make it easy to search for specific items. Buy Nothing Groups on Facebook provide a digital meeting place for neighbours helping neighbours get what they need without spending any money. Online marketplaces like Facebook Marketplace and Kijiji make the experience of finding items others have listed near you as smooth as (vegan) butter. And in the year of COVID-19, porch pickups and socially distanced drop offs make getting gifts pretty safe.

But it doesn’t end on the Internet. Free Stores and Really Really Free Markets provide people with physical spaces to recirculate items for free within their community (think Little Free Libraries but for all the things!). Community swaps like Toronto’s Holiday Gift Swap (run annually in non-COVID times) provide the same experience but focused specifically on giftable items.

As the stigma around giving secondhand gifts melts away and demand for the preloved grows, popular secondhand platforms respond in kind. Poshmark launched a Gift Market, Kijiji runs Holiday campaigns and Bunz Trading Zone introduced the #GiftIt hashtag on their app. This further reinforces the normalcy of giving secondhand and further prepares the soil for a truly circular economy to take root and thrive.

As we advocate for government action to scale the circular economy, we can begin to throw our collective weight against the grain of traditional consumption and create demand for the wonderful world of the preloved.

And it can start with what you put under your Christmas tree this year – and years to come. Happy gifting!

Greenpeace is a people-powered, science-based, and action-oriented organization that does not take money from corporations or governments. This means we rely on individual donations from generous people like you to carry out our work.

Take action

Discussion

Tell family and friends that you are donating to a charity instead of buying them gifts. There are so many people who have definite "needs" and not just "wants". This will also help save the environment.