Seabed mining is the latest threat facing the oceans. If seabed miners are given the go-ahead to plunder the ocean floor, it could be devastating for marine life. That is on top of the pressures from overfishing, the climate crisis and pollution.

So far, there is no commercial seabed mining anywhere in the world. But here in Aotearoa, wannabe miners would like to get their hands on the South Taranaki Bight, and other companies are desperate to start deep sea mining in the Pacific.

Here’s everything you need to know:

What is seabed mining?

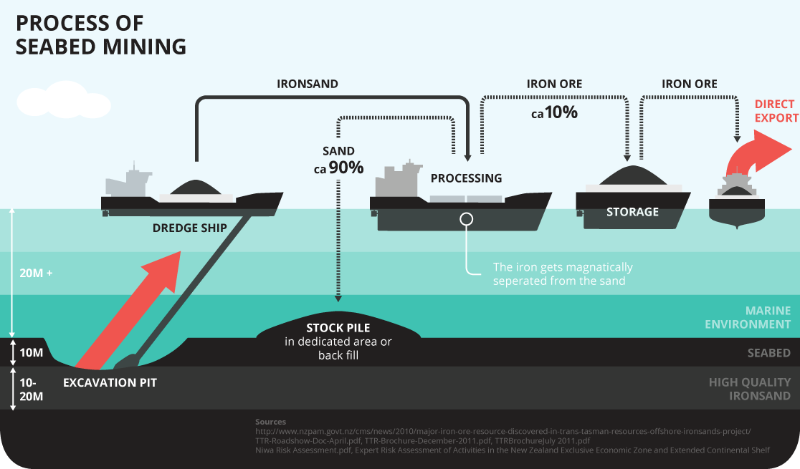

Seabed mining involves dredging up the seafloor to extract metals and minerals.

Then unwanted materials are dumped back into the sea, smothering the surrounding area with a sediment plume, like a dust cloud, which will travel for kilometres. Both the dredging and the dumping are likely to cause extensive environmental damage.

Some of the deep sea areas where seabed miners want to excavate are also the areas that support some of the most unique and least understood biodiversity on the planet.

Deep sea mining is seabed mining

The terms seabed mining and deep sea mining are two sides of the same coin. Both mean plundering the ocean floor to extract minerals and metals, leaving devastation in place of diversity. Typically, the term deep sea mining refers to mining polymetalic nodules from the seafloor of the deep sea. Seabed mining typically refers to shallower mining where the sandy seafloor is sucked to the surface in large quantities where minerals are extracted from it.

How does seabed mining work?

Seabed mining in the South Taranaki Bight would involve a suction pump like a massive vacuum cleaner that sucks up sand from the seabed to a dredger ship above. The sand would be sorted while still at sea, with the minerals or metals extracted and exported offshore. Whatever is left is dumped back into the water, smothering the surrounding area with the sediment plume.

What are the risks of seabed mining?

Seabed mining is a relatively new and experimental technique. Much of the science around its environmental impacts is incomplete.

We know less about the deep sea than about the surface of the moon. In fact, it was only in July 2024 that “dark oxygen” was discovered. Strange potato-shaped metallic lumps – polymetallic nodules – are producing oxygen on the deep sea floor – and companies want to mine them.

We don’t know the full significance of this discovery yet, but we do know now that these nodules have a role within the deep sea ecosystem. And it highlights how damaging it could be to destroy an ecosystem we barely understand, and yet depend on.

Read more: What the discovery of dark oxygen means for seabed mining

Seabed mining would be devastating for the fragile ecosystems, wildlife and environment. Below are just some of the risks seabed mining would pose:

- Noise pollution – Seabed mining is a very noisy process. Scientists are concerned that the noise from the seabed mining machines would harm mammals like whales. Many marine mammals rely on sound to communicate, navigate and forage. Studies have found that noise pollution can disrupt this behaviour.

- Destruction of habitats – When scooping up sand, seabed mining would hurt habitats and creatures on the seabed, like coral, anemones and octopus

- Sediment plumes – Seabed mining would also create massive plumes of sand when it is disposed of. These sand plumes would clog corals and sponges and likely smother the animals and ecosystems on its path.

- Blocking green investment – The South Taranaki Bight is reportedly a prime location for an offshore wind farm. Investors have since pulled out from this project, citing it as incompatible with Trans-Tasman Resource’s seabed mining plans.

The scariest thing is we don’t yet know the full consequences that seabed mining would have. If approved, Trans-Tasman Resources would be the first large-scale seabed mining project in the world.

What is the long-term impact of seabed mining?

Apart from the direct impact of seabed mining, there could also be knock-on effects that can take longer to recognise.

Look at this image here from the deep sea off the coast of South Carolina. It’s the chilling aftermath of the world’s first-ever deep sea mining site. What makes this really shocking is it was mined in 1970, and yet it looks as though it happened yesterday.

Fifty years have passed since the seabed was disrupted by a deep sea mining test, and yet, there is no sign of recovery. What was once a vibrant marine ecosystem now resembles a barren wasteland, a testament to the destructive greed of industry. Seabed mining risks causing serious and irreversible damage to oceans.

Seabed mining is the latest form of colonialism

Seabed mining is just the latest form of colonialism. Once again companies are lining up to engage in another destructive, extractive industry that will harm Indigenous Peoples. For many Indigenous groups, especially those in the Pacific, the sea has deep cultural significance and is important to their livelihoods and food security. They know that harming the ocean and the creatures that live in it also harms their communities. They know that people are not separate from the environment; instead, they are a part of it, and their well-being is linked to it.

What is the threat of seabed mining in Aotearoa?

Seabed mining is an immediate threat in Aotearoa. Australian-owned Trans-Tasman Resources (TTR) has fought for more than 10 years to start seabed mining off the coast of Patea in the South Taranaki Bight.

Find out more: Seabed mining in Aotearoa

Deep dive: Who are Trans-Tasman Resources?

If this goes ahead, it would be the largest project of its kind anywhere: an underwater open-cast mine that would pull millions of tonnes of iron sand from a 66-square-kilometre area.

TTR wants to extract minerals and metals from the rich iron sand off Taranaki. These include vanadium, magnetite and titanium oxide.

But the South Taranaki Bight is home to a rich, diverse and unique marine life, including pygmy blue whales, endangered Māui dolphins and kororā (little penguins).

Opposition to seabed mining in Aotearoa

Local iwi and hapū, environmental experts, community groups, surfers, the fishing industry, the offshore wind energy industry and the local council have strongly opposed Trans-Tasman Resources for more than 10 years.

In March 2024, Trans-Tasman Resources tried again to gain consent to mine the ocean in the first of three planned hearings of the Environmental Protection Authority in Hāwera. They pulled out of the hearings after the first one, but it was clear again that they could provide no evidence that seabed mining would not cause significant harm.

In September 2024, Greenpeace activists occupied the offices of Straterra in Wellington to bring awareness to the fast-tracked threat of seabed mining. Straterra is a group that represents the mining industry in New Zealand. Its members include Trans-Tasman Resources.

But Greenpeace and representatives of Taranaki iwi Ngāti Ruanui wanted to send a direct message to TTR’s Australian owners Manuka Resources, letting them know that seabed mining wasn’t wanted in Aotearoa. In November 2024, they disrupted Manuka Resources’ annual general meeting in Sydney.

Seabed mining is also opposed by off-shore wind developers. They have warned that if Trans-Tasman Resources gets the go-ahead to mine the seabed of the South Taranaki Bight, it would spell the end of New Zealand’s chance to embrace offshore wind. The off-shore wind developers say that seabed mining will significantly disrupt the seafloor up to a depth of 11 metres. That would mean an offshore wind electricity generation industry could not be established if seabed mining was underway.

The Fast-Track Approvals process

TTR pulled out of the Environmental Protection Authority hearings when the Luxon government announced the Fast-Track Approvals Bill. Trans-Tasman Resources applied to join the Fast-Track Approvals process, bypassing local opposition and environmental concerns.

The Fast-Track Approvals Law will allow development projects to go ahead without having to go through the usual checks and balances. Approvals will be assessed on economic criteria, totally overriding environmental criteria or public input. This means that previously rejected developments can now go ahead – like seabed mining in the South Taranaki Bight, which was rejected because it failed to prove it wouldn’t cause material harm to the environment.

Why seabed mining matters globally

If TTR is given permission to mine the seabed in Taranaki, that could open the floodgates to this dangerous new industry to gain a foothold here, but also across the Pacific, and around the world.

In Aotearoa New Zealand and across the Pacific, generations of Indigenous Peoples have suffered from the effects of colonial, extractive industries. These industries have caused biodiversity loss, accelerated the climate crisis and caused greater inequity. New attempts to mine the seabed here and in the Pacific by The Metals Company perpetuate colonisation and extractivism and we must resist.

Learning from the past

We have the benefit of being able to learn from the past. We know that burning fossil fuels is contributing massively to climate change. We have to be wary of giving another extractive industry the green light. Ecosystems that are thousands of years old cannot be remade. We must learn from our previous mistakes and put protecting nature before mining company profits.

What you can do to stop seabed mining

The fight to prevent Trans-Tasman Resources from opening a giant seabed mine off the Taranaki coast is set to escalate. Iwi and hapū, community groups, environmentalists, commercial fishers, and tens of thousands of people around this country are determined to resist it.

But to win we’re going to need as many people as possible with us.

Support the fight against SBM in Aotearoa and the global fight against Deep Sea Mining in the Pacific and beyond.

All life on Earth depends on the ocean. Together, we must protect it from this new destructive industry.

Seabed mining is a new threat to the oceans. Now is our chance to prevent the destruction before it’s too late.

Add my name