The Three Waters reform programme began after an inquiry into the Havelock North tragedy – the largest recorded outbreak of waterborne disease in the country, which killed four people and caused illness in 5,500. It was caused by the poor regulation of agriculture which led to the water supply becoming contaminated with campylobacter from sheep faeces. Today, around one in five New Zealanders are being supplied with drinking water that is not guaranteed to be safe from bacterial contamination and up to 800,000 are exposed to potentially hazardous levels of nitrate in their drinking water.

The Government is now proposing a massive overhaul of how the three waters – which are: 1) stormwater, 2) drinking water, and 3) wastewater – are managed in Aotearoa. Essentially, the reforms will shift control of the three waters from the country’s 67 local councils to four new publicly-owned regional entities. These four new entities will be owned by the Councils in the service area of the respective entities and they will be co-governed by Councils and Mana Whenua in that area. The entities will take ownership of three waters infrastructure, be financially independent of Councils, have the ability to charge the public for use of the three waters, and be able to borrow more debt. Essentially, the Three Waters Reform reorganises the water assets so that the new water entities can levy water charges and sustain their own debt without having to ask permission of rate and tax payers.

Does Greenpeace support the Three Waters Reforms?

Greenpeace supports these Three Waters reforms but wants to see some changes to ensure that people’s health and the health of our environment are protected and Te Mana o Te Wai is upheld. Greenpeace also supports co-governance of the three waters as an essential part of the plan. It is consistent with Te Tiriti o Waitangi and would be a positive step for governance in Aotearoa and the health of our water.

Rivers and harbours should not be treated like dumping grounds for sewage and stormwater runoff. New Zealanders should be able to trust that the water in their taps is safe to drink and won’t make them sick. But sewage is running through the streets of Wellington, many rivers and beaches are unsafe to swim in and people are getting sick from drinking their tap water.

That’s because after decades of the Government failing to regulate intensive agriculture, New Zealand’s drinking water, lakes, rivers and harbours have become increasingly contaminated with pathogens – like those that caused the Havelock North outbreak – and with worsening nitrate contamination which risks reproductive impacts and colorectal cancer.

Changes required to Three Waters

This failure to regulate intensive agriculture, coupled with massive underfunding by Councils of three waters infrastructure, has brought New Zealand’s water systems to breaking point. For those suffering water-borne illness, it is already broken. So reform is needed, and it is needed quickly. The current Three Waters Reforms will help somewhat, but they are missing one crucial step that must happen to ensure that everyone has access to clean drinking water in Aotearoa. That step is to stop the pollution of drinking water in the first place.

The biggest threat to safe drinking water is the pollution and contamination of the sources of our drinking water – which are rivers, lakes and aquifers. As a result of land use practices like intensive dairying and synthetic nitrogen fertiliser use, drinking water is sometimes so contaminated it is undrinkable and needs costly endpoint treatment to make it drinkable again. The most important thing the Government needs to do is to regulate the industries that are polluting drinking water in the first place. Two of the biggest polluters are intensive dairying and synthetic nitrogen fertiliser. If we are to protect our drinking water sources now and into the future, we must stop the massive volume of nitrogen and animal excreta pouring onto our land and into our waterways, causing algal blooms, waterborne illness, and seeping nitrate.

Greenpeace is calling on the government to phase out synthetic fertiliser, reduce stocking rates, and invest in the shift to plant-based regenerative organic farming that works with nature, not against it. These are all necessary steps to protect New Zealand’s water.

The other part missing in the reforms is any moves to create a more fair and equitable model of dealing with the cost burden of decontaminating dirty water. The cost of treating contaminated water to make it safe again depends on the quality of the source water, so the more polluted it is, the more expensive it becomes to treat. At the moment, the public are footing the bill for cleaning up water that has been polluted by companies, like agri-chemical giant, Ravensdown, who are making massive profits but leaving behind a deadly mess. It is a classic example of privatising the profits and socialising the costs of polluting production.

The Government needs to implement a polluter pays model in the form of a levy on agrochemical producers such as Ravensdown and Ballance, and on agricultural processors such as Fonterra, as part of these reforms. The companies that contaminate our drinking water sources in the first place should be the ones that foot the bill for the expensive infrastructure needed to make water safe to drink again.

Three Waters current management

Currently, New Zealand’s 67 local authorities own and operate the majority of three waters services. Around 85% of New Zealanders receive their three waters services from their councils, with the remainder being provided by smaller private and community-based schemes. The regulation and control of the sources of pollution into drinking water sources is managed by Government and Regional Councils.

Three waters infrastructure includes a complex and very expensive network of; drinking water and wastewater treatment plants, pipes and pump stations and stormwater network assets. It is one of the country’s most significant infrastructure sectors and is expected to cost $2 billion per year to operate, and around $2.7 billion per year to maintain and upgrade the networks. This infrastructure has been severely underfunded by many Councils and much of it is now aged, degraded, deteriorating and in no state to cope with the intense flood events that climate change brings. Sewage overflows and unsafe drinking water are now common.

A recent report found that the systematic underfunding in three waters assets by local authorities has meant that between $120 billion and $185 billion of investment will be needed over the next 30 years. On top of this underfunding, land-use and agriculture is severely under-regulated and this is causing increasing contamination of drinking water sources with pathogens and nitrate.

Environmental and human health impacts of current water management

The insufficient regulation of land-use coupled with under-investment in, and poor design of three waters infrastructure causes: sedimentation, and bacterial, nutrient and heavy metal contamination of freshwater and coastal areas. In some cases, this is leading to human illness from unsafe drinking water.

It’s important to note that the main environmental issues arising from three waters infrastructure itself are sewage overflows and discharges and stormwater run-off. In terms of the scale of environmental degradation in Aotearoa, pollution from these sources is comparatively small. This is because it mainly affects urban waterways which represent less than one percent of New Zealand’s total fresh waterways. The volume of pollution from agricultural land-use is vastly bigger and is the greatest threat to drinking water quality in Aotearoa.

Examples of some of the impacts of three waters mismanagement until now include:

- The Havelock North tragedy – the largest recorded outbreak of waterborne disease in the country, killing four people and causing illness in 5,500.

- Recent infrastructure failures in Wellington has led to sewage discharges in the streets.

- Approximately one in five New Zealanders are supplied with drinking water that is not guaranteed to be safe from bacterial contamination.

- Elevated levels of lead have been found in the water supply in Dunedin

- The Ministry of Health reports there were 27 permanent and 56 temporary boil water notices in place for the reporting period (1 July 2020 – 30 June 2021), affecting roughly 40,000 people.

- Resource consents are required for the discharge of treated wastewater from treatment plants in all regions. A 2019 report found that at that time nearly a quarter of wastewater treatment plants were operating on expired consents.

The proposed Three Waters reforms

There are two parts to the reforms. Firstly the establishment of a new Three Waters regulator – Taumata Arowai, which has already been completed. Secondly, the establishment of four new water service entities which will take over control from the councils – this part is still in train.

The four new entities

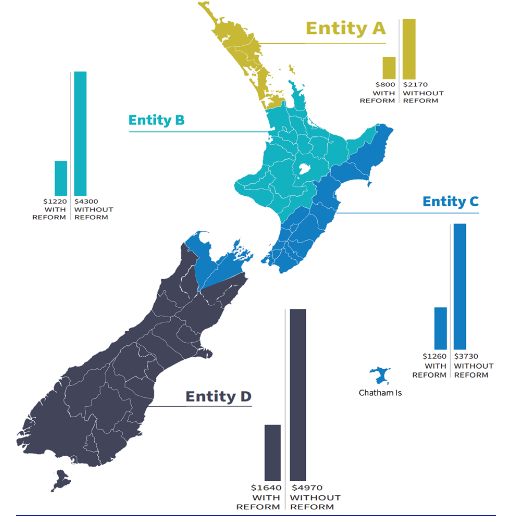

The Government has introduced the Water Services Entities Bill to establish these four public entities which will take over three waters control by July 2024. This Bill sets out the ownership, governance, accountability arrangements relating to these entities. There will be a second Bill also introduced in late 2022 to transfer the assets and liabilities from local authorities to the water services entities, establish their powers and functions and integrate them into other regulatory systems, such as resource management and economic regulatory regimes. The map showing the boundaries of each entity’s service area is shown below.

DIA 2022 Three waters reform case for change and summary of proposal

Ownership

The entities will assume ownership of Three Waters infrastructure, as well as associated debt and revenue, from local authorities and will be financially independent from the local authorities. They will be publicly owned statutory entities. Each entity will be a body corporate and will be co-owned by the councils in its service area. Council ownership will be through a shareholding structure where each council will be given one share in the water services entities per 50,000 people in its district. Councils will be the only shareholders, shares cannot be sold or otherwise transferred; and do not come with a financial benefit or liability. While larger councils will have a greater number of shares (based on population), this does not come with additional influence over the entities – each Council just gets one vote. The entities will not have a profit motive or an ability to pay dividends to shareholders. Mana whenua in the entities service area will not own the new entities but they will co-govern them with the Councils. An equal number of mana whenua representatives will sit on the regional representative group as there are councils, as explained below.

Governance

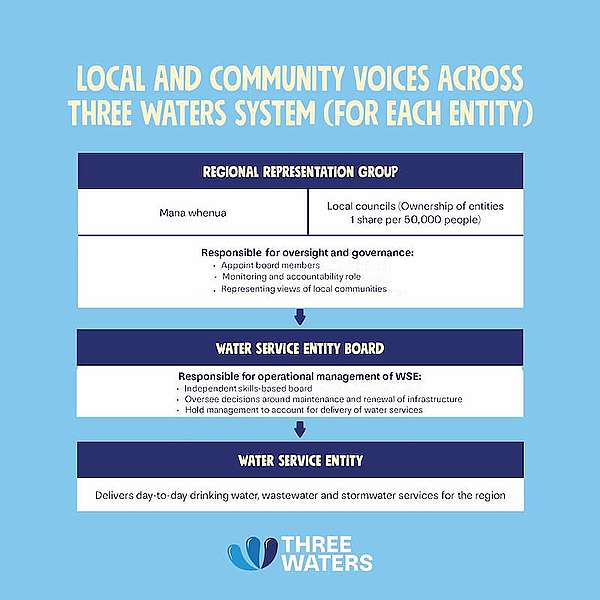

The water services entities two-tier governance arrangement would comprise of:

- A Regional Representation group, which provides joint oversight of the entity by an equal number of representatives of the territorial authority owners and mana whenua from within the entity’s service area.

- A water service entity board that is independent and skills based which will be appointed by the Regional Representation group and will run the day-to-day management of the entities and oversee the maintenance and renewal of this infrastructure

DIA 2022 Three waters reform case for change and summary of proposal

Crown direction, monitoring and intervention

The Minister will be able to make a National Policy Statement setting out the Government’s overall direction and priorities for water services which water services entities must give effect to. The Minister is also able to appoint a department as a Crown monitor and the Bill provides the Minister with powers of intervention based on a similar framework in the Local Government Act 2002. The Minister can appoint a Crown review team, a Crown observer, or, as a last resort, a Crown manager.

Accountability and transparency

The Office of the Auditor General has raised concerns that “as currently drafted in the Bill, the accountability arrangements and potential governance weaknesses, combined with the diminution in independent assurance noted earlier, could have an adverse effect on public accountability, transparency, and organisational performance.”

Treaty implications

Cabinet has agreed to recognise and provide for iwi/Māori rights and interests in the reform with a specific focus on service delivery. It is proposed that iwi/Māori will have a greater role in the new Three Waters system, including pathways for enhanced participation by whānau and hapū as these services relate to their Treaty rights and interests. Redress set out in Treaty settlement legislation will continue to apply and, where relevant, be explicitly provided for in the new regime. It is expected that protection for current Treaty settlements will be within the suite of establishing legislation.

Controls against privatisation

Safeguards against privatisation or loss of control of water services and infrastructure have been put into the legislation. For one of the four entities to divest, lose or privatise any assets it requires:

- Firstly, the agreement of 75% of the council and iwi members of the regional representative body (who are present and voting). If this is achieved, the privatisation proposal is presented to the territorial authorities that own the water services entity.

- There must then be unanimous support (not just those present and voting) by the territorial authorities before the privatisation proposal proceeds to a poll.

- A local poll of the water entity service area must then be held and it must get 75% support for the privatisation to proceed.

The ownership/governance structure outlined in the above section also protects against privatisation to some extent because mana whenua will hold equal seats on the regional representative group. This group must have 75% present and voting votes in favour of the privatisation proposal to go to the next step, and it seems unlikely that mana whenua would support the sale of water assets.

The council-iwi working group on the reforms recommended an additional entrenched clause: That the sale or transfer of any infrastructure would require the agreement of at least 75% of all MPs. This clause has not made it through to the Bill itself because the Government needs to have at least 75% MPs in support of adding the entrenchment clause, but the National party has refused to support it.

Taumata Arowai

In 2021 the Government also established a new Three Waters regulator through the ‘Taumata Arowai – Water Services Regulator Act.” Taumata Arowai is a Crown entity with a Ministerial-appointed board and a Māori Advisory Group, Te Puna. It is the regulator for drinking water, and from 2023 it will also monitor and report on the environmental performance of wastewater and stormwater networks. In 2024, it will assume responsibility for oversight of wastewater and stormwater networks, becoming the Three Waters regulator for Aotearoa. The chief executive of Taumata Arowai has a statutorily independent function – to monitor and enforce compliance by water suppliers with relevant drinking water legislation and standards.

According to the staff profiles of the Board and the leadership team, there are no freshwater scientists in leadership positions at Taumata Arowai.

MfE and Regional Councils still have the power to set, monitor and enforce policy on protection of source water. Taumata Arowai recommends the drinking water standards (DWSNZ) for drinking water suppliers which lays out the level of contaminants allowed, and monitors them to ensure they are satisfying their duty to provide safe drinking water. One of the first things Taumata Arowai did was recommend new drinking water standards that increased the permissible level of 17 contaminants in drinking water. Greenpeace expressed our concern that under the pretext of protecting drinking water Taumata Arowai acted as a wolf in sheep’s clothing.

What needs to change in the Three Waters reforms

The potential environmental and social benefits of the Three Waters reforms include:

- The shift to a co-governance model which is in line with Te tiriti o Waitangi.

- Increased funding availability to fix up infrastructure

- Better availability of technical expertise in three waters management.

- It is also likely that the new entities will have a greater financial interest in protecting source water and so could become strong advocates for better land use regulation.

The risks include:

- Ongoing drinking water pollution due to insufficient controls on polluting land use

- Future privatisation of water infrastructure (however significant safeguards are now in place to prevent this)

- Decreased public scrutiny and accountability over three waters management

- An unfair funding model that disproportionately affects the poor and lets polluters off scot free

- Decreased ability for society to influence some aspects of three waters management because Taumata Arowai and the four new entities are not voted in.

Conclusion

The Three Waters reforms have the potential to significantly improve water infrastructure management, security, and drinking water quality for New Zealanders, which is why Greenpeace supports the essential plan. However, if this and subsequent governments continue to fail to protect sources of drinking water – rivers lakes and aquifers – from agricultural pollution in the forms of cow and other animal excreta, fertiliser leachate, and toxic agrichemicals, we will see drinking water quality continue to decline and massive costs put on the public for decontaminating water to make it fit to drink.

Co-governance is an essential component of the plan as it recognises the Tiriti right of Māori as having sovereignty of their resources and taonga – which water clearly is. Genuinely prioritising and upholding Te Mana o te Wai is in the interests of all peoples and species.

In addition, Greenpeace recommends:

- A polluter pays levy on agricultural processors and agri-chemical companies to fund drinking-water decontamination from their activities

- Phase-out of synthetic nitrogen fertiliser

- Lowering of dairy cow stocking rates