One of the most extraordinary experiences I’ve had as a marine biologist was when we were tracking lobsters on Wolf Island in the Galápagos Islands in 2003. The work occurred at night, so I used to take a nap after lunch. One day, I was still asleep in my pyjamas when suddenly, someone came running to tell me there was a whale shark under the boat. I thought they were joking, and tried to ignore them, but they kept insisting, and when I looked over the deck, sure enough, there it was. I was so excited that I just jumped into the water. The crew passed me a diving mask, and I spent the next 45 minutes swimming around in my pyjamas with a juvenile whale shark. I started asking myself where it had come from and where it was going. Years later, I would discover that juvenile whale sharks are actually quite rare in the Galápagos. Most whale sharks here are large adult females, and we still don’t know why!

The natural environment has always fascinated me. Initially, I wanted to become an ornithologist because I love birds. I never saw myself as a marine scientist until I was about sixteen when we went on a school trip to the north of Spain. We spent a week in Galicia doing science work on the seashore and boats, which changed everything for me. After finishing my PhD in Ocean Science in 2001, I came to the Galápagos, and I’ve been involved in research here ever since.

I joined the 2024 Greenpeace Galápagos expedition on the Arctic Sunrise to help gather information on the variety of fish and larger marine life that live in the oceans around the Galápagos Marine Reserve. The open ocean is much more vulnerable than we thought, and we need a baseline to measure change and improve the conservation of this area.

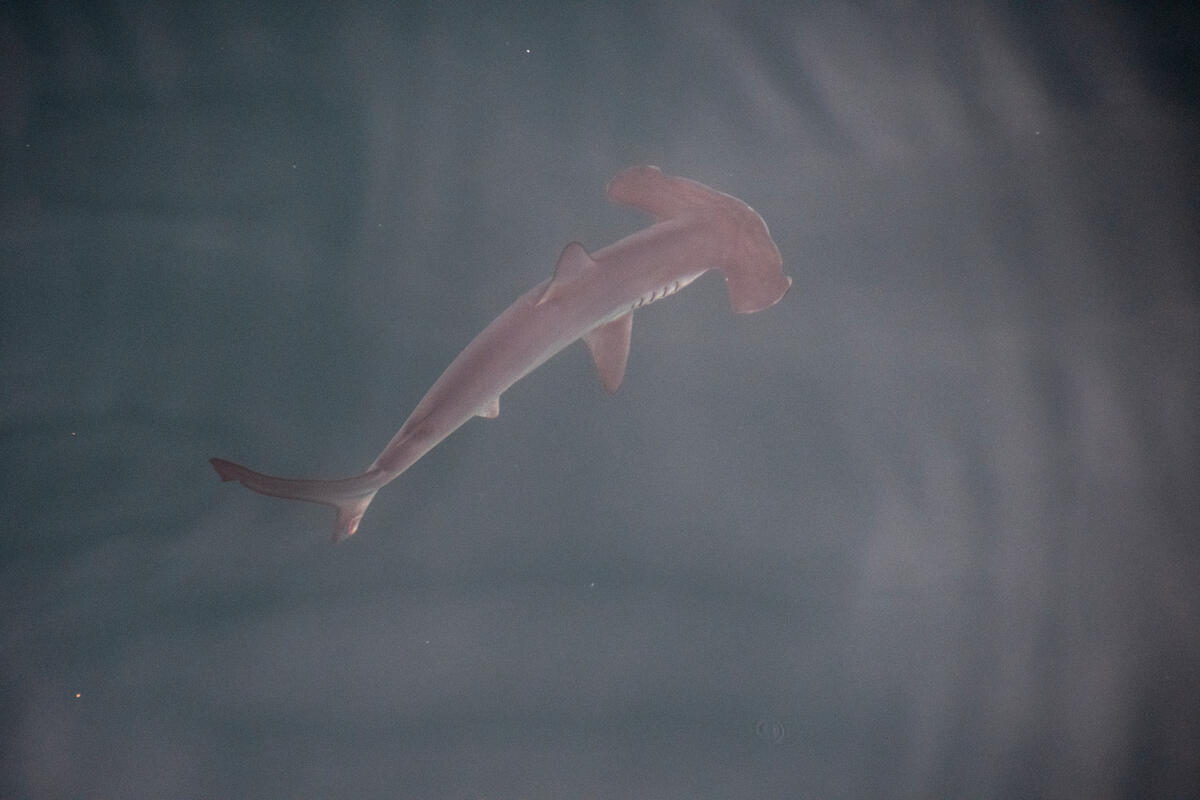

The primary goal of this expedition was to track sharks around the Galápagos Marine Reserve and understand to what extent they live inside protected waters and move out to unprotected waters. In this region, there are several endangered or critically endangered migratory species that we’re interested in, like hammerhead sharks, which move between the Galápagos Island and Cocos Island along a swimway called the Cocos Ridge.

Human activities like overfishing, poaching, or ship strikes directly impact these creatures, and there are things we can do about these dangers. By studying the populations, habitats, and migratory routes of the affected species, we can create areas to protect them.

The historic Global Ocean Treaty is a tool countries can use, but they must first ratify it as quickly as possible. The Treaty can only be brought to life once at least 60 governments have written it into their national laws.

If we’re serious about protecting 30% of the world’s oceans by 2030, political leaders must prioritise Treaty ratification or time will run out. Leaders come and go, but the ones who ratify the Treaty will leave a legacy of lasting impact for generations to come.

The oceans not only provide a home to many incredible species, but they’re also extremely important in regulating the climate. There is no green without blue. The high seas comprise over 60% of the world’s oceans, and whether we think about them or not, they are relevant to our daily lives. Oceanographers recently discovered that Galápagos can affect the climate as far away as the United Kingdom thanks to a system of currents that transports heat throughout the oceans.

We’re one little blue planet floating in the middle of a vast, cold emptiness of space. Without the oceans, there is no life on Earth; that’s why we simply cannot fail to protect them.

Alex Hearn is a Professor of Marine Biology at Universidad San Francisco de Quito in Ecuador and co-founder of the Galápagos Whale Shark Project and MigraMar.

Call on the Foreign Affairs Minister Winston Peters to create new global ocean sanctuaries and protect our blue planet.