There’s an old saying isn’t there: “everything’s a nail to a hammer.”

And it seems that’s the whole thinking behind the so-called “Wellbeing Budget” due out this week.

We need to open up the toolbox, they say, take different approaches to measuring and improving our lives.

But there’s one crucial omission which makes this much-vaunted progressive document an exercise in narrow thinking.

Yes, they’re looking to retire the bluntest tool in the belt, that is GDP per capita – dividing the value of goods and services in the economy by the number of people who live here and using that as a measure of success.

There is an ambitious attempt here to measure not just the gross wealth but how it’s shared out – to look at homelessness, child poverty and inequality rightly as red marks in the country’s ledger books.

But if you take a close look at the Treasury’s blueprint for this Budget there’s a glaring omission.

Climate change – conspicuous by its absence.

Wellbeing economics has been defined as the expansion of the capabilities of people to lead the kind of lives they value. Could there be anything more central to wellbeing than a liveable Earth?

Why would you relegate combating climate change to just one of the 60 odd measures of success when, if we fail at that, we’ve failed full stop. We all have to s쳮d at this to just survive. All of us, every country, every corporate, every government. We’re living through a climate and ecological emergency, so let’s act like it.

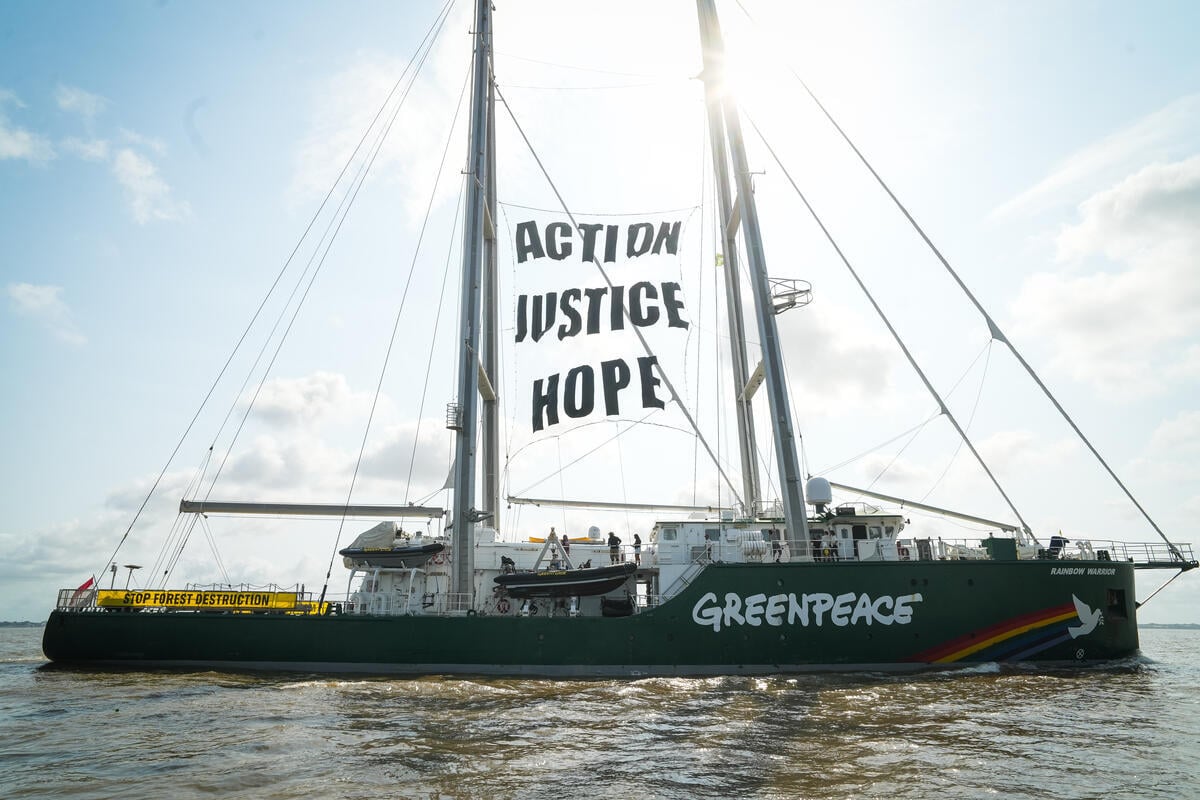

Now you could say that Greenpeace in pointing this out, is exhibiting its own nail and hammer thinking, another special interest group pushing a special interest barrow. Except that this grim future is now special and pressing for all of us. Read the IPCC report on climate or the IPBES report on species extinction and try to pretend otherwise.

That is why there are mounting calls for a climate emergency. A recognition of the need to escalate this to an overarching policy which runs through every bit of accounting we do, be it personal expenditure, corporate balance sheets or the nation’s accounts. It’s not a budget line entry but a mission statement for avoiding extinction.

We don’t know all of the details of the 2019 Budget yet, but you can learn a lot by looking at its guiding document – the Treasury’s Living Standards Framework published on December 4.

Finance Minister Grant Robertson described it as an “exciting day”.

There were vague mentions of “sustainability” and the “health of our environment” and a “low emissions economy.” Great.

But it is hard to glean any sense of urgency, any reflection of the environmental and ecological juggernaut about to ram into us. It is hard to believe that halfway through 2019, we are still parked up with this blind spot of complacency.

In a pre-Budget Speech to the Wellington chamber of commerce on 14 May, Mr Robertson referred to building a sustainable economy as a “long term economic challenge”.

The climate crisis is not a long term economic challenge. It is a pressing threat which underpins all future wellbeing.

One of the precursors of this week’s Wellbeing Budget is something informally entitled How’s Life? which the OECD started doing back in 2011. The “Better Life Initiative” took 11 measures of wellbeing that include work-life balance, health and social connections as well as the old chestnuts of income and wealth. No obvious mention of climate crisis in the latest OECD dashboard. Just people’s thoughts on air and water pollution.

Given the threat to human life there would be a strong argument for including climate in the adjoining section on personal security. That’s taken up by concerns about homicides and feeling safe at night. What about feeling safe about the idea of bringing children into the world?

New Zealand’s own Treasury dashboard, as they’re fond of calling such things, is divided into three sections: Our People, Our Country and Our Future. Environment seems to slot into the third category under the subheading Natural Capital. “All aspects of the natural environment needed to support life and human activity.”

“Whilst the capitals are used to organise the indicators of future wellbeing, they do not constitute wellbeing on their own,” says the Treasury. Do they not?

“There are many characteristics of the capitals that affect future wellbeing, such as “the degree to which the capitals are resilient to potential shocks.”

The sort of language which appears to compare climate breakdown to a downturn in the Dow. A crisis which threatens our health, homes, communities, food security, livelihoods and our children’s chance at a future.

It’s also alarming how the Treasury’s framework deals with those with the most to lose. Children and young people. The school climate strikes are visceral reminders of how much this new generation appreciates the link between the climate and future well being. Unfortunately the Treasury leaves them out of the equation entirely.

The Chief Economic Adviser Tim Ng said this at the December framework launch: “The wellbeing of children and young people are not directly represented in this first version of the LSF Dashboard. This is in large part due to children and young people not being well represented in survey-based data collections on which the Dashboard draws heavily.”

We need sweeping changes across all sectors – from land use, to the way we generate and use energy in New Zealand. Judging from the banners at the school strike, kids know this already.

If this Government really is about more than just rhetoric, then they need to prove it.

Budget 2019 should be brimming with strong policy and financial commitments that will bring a close to the era of polluting energy and make the transition to clean and affordable energy for New Zealand. Done in a just way, where no workers or communities are left behind.

In terms of agriculture, a good start would be for the Government to stop subsidising industrial agricultural pollution to the tune of $1 billion per year through its exclusion from the ETS. We must also reduce the number of dairy cows in the country, and ban synthetic nitrogen fertiliser, which intensifies dairy and destroys our climate and our rivers. Public money should instead support farmers to transition to regenerative practices that store carbon and bring back biodiversity.

In the energy sector, we must end fossil fuel exploration on land and sea, including revoking permits for new oil and gas exploration. Investing in technologies that can bring good jobs to the regions (like onshore and offshore wind) or provide families and communities with more control over their energy (like solar) is just common sense. We also need significant investment in electric and active transport, together with a plan to phase out the import of petrol and diesel vehicles.

What’s the point of all these fine words and thoughts about wellbeing, all that laudable empathetic accounting, all those useful tools for building, when your house is on fire?

[ This story was originally published on Stuff ]

Donate to Greenpeace today. We take no money from corporations or governments. Our independence and ability to speak and act freely is our greatest strength. To maintain that freedome, we rely on the generosity of people like you to keep us in action.

Take Action