RMA Reform Minister Chris Bishop is one of three ministers who will have unprecedented power to approve any development project under the Fast-Track Approvals Bill. He has written to over 200 organisations inviting them to apply under it, but the catch is that he won’t tell the public the names of the organisations or how they were chosen.

Two seabed mining companies – Trans-Tasman Resources and Chatham Phosphate Company – that received the letter have publicly stated that they have been invited to re-apply under the Bill. Both had their applications turned down previously.

Chatham Rock Phosphate wants to mine phosphate from the seabed near the Chatham Islands. Their application was rejected by the Environmental Protection Authority in 2015 because “the mining would cause significant and permanent adverse effects on the seabed environment. The economic benefit to New Zealand of mining the area would be modest, at best.” At the time, Forest & Bird argued the proposal could threaten feeding grounds on the Chatham Rise of five critically endangered seabird species, including Chatham taiko, Antipodean albatross and Salvin’s albatross.

TTR had their huge proposed seabed mining operation off the Taranaki coast turned down in 2013 because the evidence showed it would cause massive harm to the marine environment, including impacting marine mammals such as the pygmy blue whale and the critically endangered Māui dolphin. They plan to mine 50 million tonnes of seabed in the South Taranaki Bight every year for 35 years and dump what they don’t need back into the ocean. Just a few weeks ago the company withdrew its latest application, seemingly in the hope they will be able to more easily get it consented under the Fast-Track Approvals Bill.

This diagram from Kiwis Against Seabed Mining (KASM) is a good illustration of how seabed mining works.

Another potential candidate is Stevenson Mining’s Te Kuha mining proposal, which seeks consent for a coal mine on a mountaintop site near Westport. The land is home to numerous threatened species, such as the roroa great-spotted kiwi, the South Island fernbird, geckos, and 17 plant species.

Forest & Bird won a case against the mining company in the Environment Court last April, which ruled that the resource consent should not be granted. Stevenson Mining has not lodged an appeal which has led to speculation that they are also banking on a fast-track approval.

The Ruataniwha Dam project in Hawkes Bay also looks set to rear its head again. In 2018, a private interest group called Water Holdings bought the consents and intellectual property from the council after the project was rejected by the Supreme Court. They’ve already said they are waiting to see the final details of the fast-track legislation.

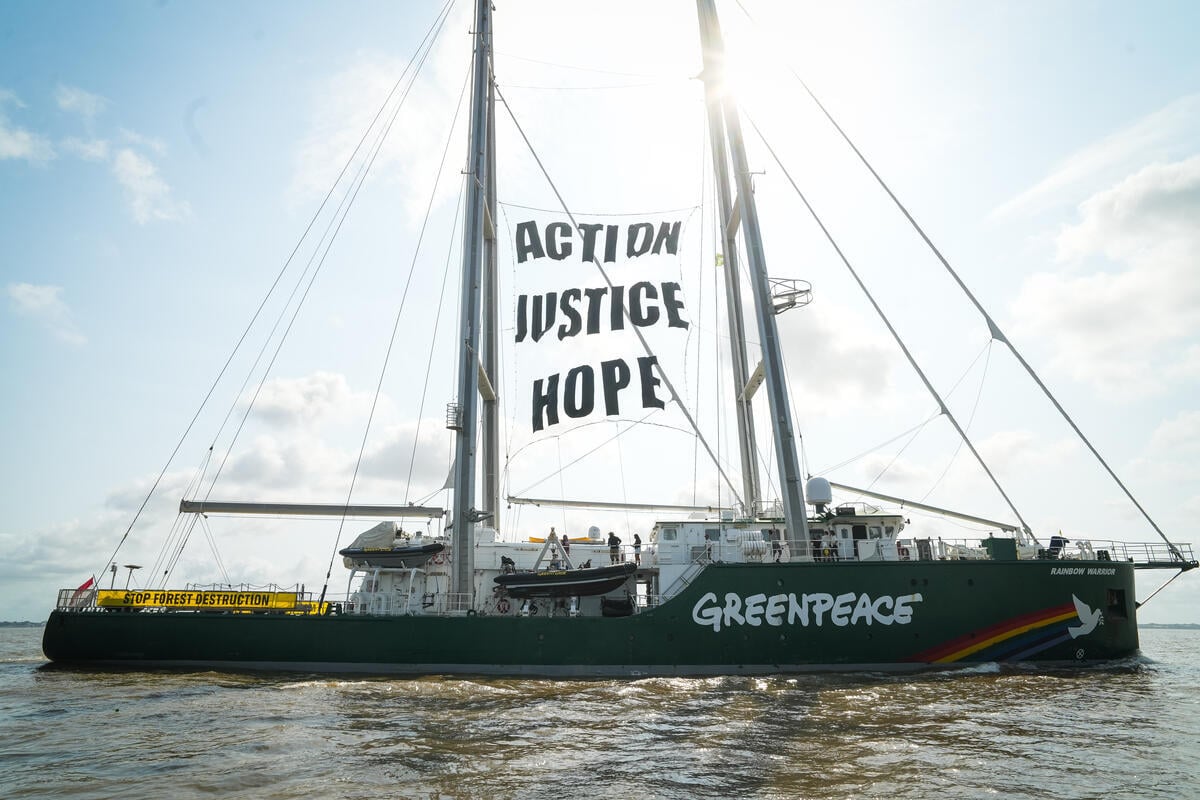

Greenpeace and others fought hard against the original Ruataniwha proposal because of the impact it would have on the river and the inevitable intensification of dairy farming that such irrigation projects rely on.

A burning issue

In the absence of a full list of organisations the minister’s letter was sent to, it is difficult to be certain which other failed or environmentally destructive developments have been invited to apply under the Bill. However, there’s no shortage of potential candidates.

On 10 March 2024, the Northern Advocate published a news story in which Kaipara mayor Craig Jepson said he wanted the Government to fast-track a giant waste-to-energy (W2E) incineration factory in Kaipara to burn 730,000 tonnes of solid waste per year from Northland and Auckland.

Previously, a similarly large W2E incineration factory that Mr Jepson was employed to promote at Meremere failed to gain consents from Waikato Regional Council in 2000. That followed a public campaign led by local community groups, zero waste advocacy groups, and Greenpeace that opposed the proposal on the basis of the toxic pollution and carbon emissions it would create.

Another large-scale W2E incineration proposal at Buller promoted by Renew Energy Ltd with the involvement of the Chinese-owned waste incineration giant China Tianying Ltd collapsed in 2018 before it received consent after the Serious Fraud Office launched an investigation into Renew Energy Ltd executive director Gerard Gallagher.

Since then, another proposal has been mooted for another large-scale W2E incineration factory in Waimate to burn 350,000 tonnes of solid waste per year, which could involve some of the same key players that were behind the Buller proposal – including China Tianying Ltd and a new company called SRRL Ltd. SRRL Ltd director Paul Taylor was also the majority shareholder in Renew Energy, and Renew Energy’s director Kevin Stratful is also a director of SRRL Ltd.

Greenpeace is strongly opposed to W2E incineration on human health and environmental grounds and suspects that there could now be an application under the Fast-Track Approvals Bill for SRRL Ltd and China Tianying to build giant W2E incineration factories at Waimate and Kaipara. A third one has also been proposed in Te Awamutu. If these are approved and they receive 35-year consents, it is estimated that they could create massive quantities of toxic ash waste and 30–40 million tonnes of carbon emissions.

They would also stymie the implementation of zero waste strategies, and create the risk of localised contamination of residents, produce, and land.

A toxic time bomb

Fast-tracking big new developments without requiring a thorough assessment of their health and environmental impacts is bad resource management and it’s bad governance. It is also bad business practice because it poses a real risk in the form of future liability for toxic site contamination and local toxic pollution of food, land and residents – especially if a company collapses or pulls out and leaves NZ taxpayers to pick up the bill to clean-up the mess.

If, at some point, an operator collapses or pulls out, the government could be forced to pay to clean up the toxic mess to the tune of millions or even tens or hundreds of millions of dollars.

For example, the Tui mine on Mt Te Aroha (Waikato) was abandoned in 1973 leaving a toxic contaminated site that taxpayers had to pay over $20 million to clean up the mess. The company mined copper, lead and zinc sulphides there which left large-scale toxic zinc and cadmium contamination.

Another is the Mapua agricultural chemicals formulation site near Nelson and the Tui oil field off the Taranaki coast.

The large NZ Fruitgrowers Company chemicals formulation site in Mapua near Nelson operated from the 1930s to the 1980s, and was heavily contaminated with toxic herbicides and pesticides. After the company was broken up in the 1980s and sold to other businesses, liability for site contamination became contested, and the Crown ended up having to pay for most of the multi-million dollar clean-up two decades later.

An even more expensive example of this is the Tui oil field off the Taranaki coast. In 2016, Tamarind Resources purchased 57.5% interests in the oil field but by 2019 the company was declared bankrupt and collapsed, leaving the Crown with a $300 million bill for safely removing the subsea infrastructure back to shore and safely decommissioning it there.

At the time that Tamarind Resources fell over, Greenpeace slammed the company for its failure to decommission the Tui oil field and described the Malaysian-owned company as “shirking its responsibilities” by allowing its subsidiary to go into liquidation leaving it absolved of responsibilities.

Greenpeace climate and energy campaign director Amanda Larsson said that, “Most New Zealanders would see it as a bare minimum that companies are required to cover the cost of cleaning up after themselves.”

Such a requirement needs to be included, if the Fast-Track Approvals Bill goes ahead, so any future collapse of a company does not leave the NZ public to pay to clean up their toxic mess.

Companies should also be required to post a large multi-million-dollar bond to be held by the Crown in the event of this happening, which can be used to pay for cleaning-up on-site and off-site contamination, and to compensate for any environmental damage they are found to have caused.

The government would also need to amend the bill to ensure that all new development projects approved are required to safeguard human health, threatened species, habitats and ecosystems and to comply with Aotearoa climate goals and existing biodiversity protections.

Transport minister Simeon Brown has now asked Waka Kotahi (NZ Transport Agency) to investigate an expensive twin two-lane 4km mega-tunnels project that would run from Wellington city centre to Kilbirnie. Electric light rail would far be less polluting and a much more climate-friendly way to improve transport capacity and travel times in the capital, but under the fast track approvals bill the environmental and human health impacts would not need to be considered.

Please take action before the end of this week to stand up for nature and democracy by raising your voice against the fast-track approvals bill.

Michael Szabo is a former Greenpeace Aotearoa Campaign Manager and a former member of the Ministry for the Environment’s Hazardous Waste Advisory Group. He is also the author of Making Waves I & II, a history of Greenpeace in Aotearoa (1971-1990; 1991-2021).

This article is a guest post and doesn’t necessarily represent the views of Greenpeace.