The landscapes and the creatures we encountered were so beautiful and precious, yet I also saw the industrial nature of New Zealand’s countryside.

This summer I was privileged to spend time in beautiful Te Waipounamu – the South Island, visiting friends and family and taking some much-needed time out in nature for a mental and physical health reset.

We camped and tramped, kayaked in the Marlborough Sounds; we walked among giant kahikatea and podocarp forests. We encountered Hector’s dolphins a dozen times. We swam in Lake Manapouri.

Lake Manapouri is pretty special! It’s ‘the birthplace of the modern conservation movement’ in Aotearoa because in 1972 more than 100,000 New Zealanders signed a petition to stop the lake level being raised for hydroelectricity generation. We travelled from the headwaters of the Waiau river at Lakes Manapouri and Te Anau, to its outflow in Te Waewae Bay where the Hector’s dolphins play.

Those landscapes and the creatures we encountered were so beautiful and precious, it brought tears to our eyes.

From the photos that were submitted by our supporters about the places you value, and are at risk, it’s clear that a lot of these places are special to you too.

But there’s a sadder side to the stunning New Zealand landscape. So many of those beautiful rivers are polluted with industrial dairy contamination. Synthetic nitrogen fertiliser and too many cows reduce river flows to a polluted trickle. Riverside signs warn of algal blooms which make it unsafe for people or dogs to swim.

The Waiau river was especially tragic to see – while New Zealanders saved Lake Manapouri, we didn’t save its river (yet). Where once the Waiau flowed at 400 cubic metres a second (cumecs), its ‘restored’ winter flow is just 14.

Those podocarp and kahikatea we walked through are remnant islands of forests surrounded by dairy farms. And where the pasture starts, the forest stops.

The Clearwater stream near Fox (Waiho), is now a green slime- filled puddle. The glacier after which the area was (re)named, is melted and now inaccessible. Cattle graze in streams and in the Haast river.

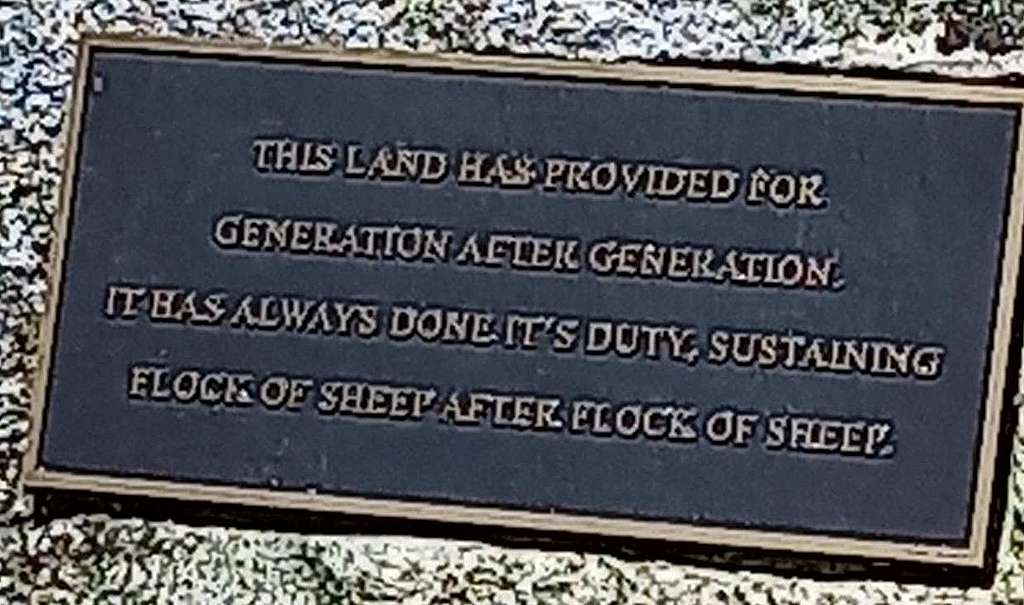

Signs at historic places now read uncomfortably. They show how today’s degraded landscapes were built from colonisation and deforestation to create farms for the empire. For example, Ship Creek near Haast hosts the last of lowland kahikatea, which stand 65m tall. Signage on the track tells the story of the rest of the forest cut down to make way for dairy farms and butter boxes.

Signs elsewhere honour the colonial purchasers of the whole of the West Coast from ‘resident natives’ in 1860, and that the land has ‘done its duty for generation after generation of settlers, sustaining flock of sheep after flock of sheep’.

The industrial nature of this landscape is clear even to tourists, who are bewildered by so many cows, irrigators that stretch across the horizon turning dryland ecosystems into an artificial green, cattle in rivers, rivers that have no water, and are unsafe for swimming, cows and sheep that bake without shelter in the heat.

And that warm sea we swam in and the sunny days we spent, are themselves symptoms of climate change, as the region experiences an extreme marine heatwave and the third drought in three years.

It’s all so sad, it brings tears to your eyes too.

While these landscapes are vast, it’s still a small world. So on our travels, it turned out that friends and family, as well as friends of friends, and strangers, are all caught up in the dairy industry too.

I took the chance whenever the opportunity arose to speak with dairy workers, fertiliser truck drivers, meat workers. All good people, caught in an oppressive economic model that devalues people, animals and nature.

I talked with a man who drives a fertiliser truck, spraying chemical fertiliser. He told me he was in the job because it’s better than working in the local dump (‘bulldozing farm waste including dead animals’), and there aren’t any other jobs around. He could see the effects on the high country, that ‘there’s too much synthetic nitrogen fertiliser, it’s getting into the lakes and rivers, there’s no way it’s sustainable’. Slaughterhouses run 24/7 killing two million bobby calves a year, and the meat worker we met at a lakeside said it breaks his heart to see the bobby calves in pens before slaughter, little and lost, trying to suckle their killers’ hands.

One couple I met told me they’d shifted to their farm for a better life for their children. They raised each of the hundreds of cows on the farm and love them. They had to argue with the absentee farm owner about why having fewer cows is good. They’ve reduced the herd from 1000 cows to 850 and plan to go down to 750. They’ve found it’s better for the welfare of the cows, the workers, and even the profit-bottom line. Yet the intensive production, the slaughter of bobby calves, and the long hours outweigh the benefits and are really getting to them, so really they’d like to leave … but they can’t leave their cows.

Everywhere I went showed me that the history of environmental destruction for dairy that went with the founding of the New Zealand nation, continues today. The branding used to sell our tourism to the world is 100% BS, and puts our tourism industry at risk. People and animals are at the heart of, and caught within this system too. There’s a class element to this industrial injustice, including for the many Filipino workers upon whom this industry depends.

These are my anecdotal experiences, but there seems to be a widespread acceptance that the industrial dairy model is unsustainable. Farmers are choosing to reduce herd numbers already for various reasons – even if investor landowners have to be convinced by the farm managers that it’s better for everyone.

Ultimately, everyone is in the industry for a better life for themselves and future generations, though that might not always pan out, and it means different things to different people whether you’re an investor or a farm worker with children.

And across the motu, people we met within the system, and outside it, are doing inspiring mahi to restore wetlands, plant trees, build community gardens, give a better life for animals and for people, and work with catchment groups to reduce water takes and fertiliser use. As within our Greenpeace movement, they are striving to build a new world in the shadow of the old.

Let’s make 2023 the year we end big dairy’s hold on our special places, and build that new world for people, animals and nature.

Join our call on the Government to go further than the Climate Commission’s inadequate recommendations and cut climate pollution from NZ’s biggest polluter: industrial dairying.