Susi Newborn — one of the most skilled and effective activists in Greenpeace’s 52-year history — passed away on the last day of December 2023. She is remembered fondly by her beloved children, Brenna, Woody, and Naawie; her granddaughter Toody; by her ex-husbands, Martini Gotje and Luc Tutugoro; and by friends, colleagues, and shipmates around the world.

In 1977, when Susi arrived in Canada for her first Greenpeace action to protect infant harp seal pups in Newfoundland, she was already something of a legend. Journalistic tradition would have me refer to her as “Newborn,” a name that rang with significance, but I can only think of her as Susi, the tough, smart activist from London.

Susi was born in London in 1950, from Argentine parents. Her mother had grown up among the Buenos Aires elite and knew famous artists such as Raul Soldi and Mexican muralist Don Sequeiros. Susi’s godmother was a founding member of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) in the UK, and a colleague of Bertrand Russell. Susi grew up meeting writers, philosophers, and artists.

Susi’s father was an Argentine Embassy diplomat, whom she described as “a deeply spiritual man.” He told her about meeting Mahatma Gandhi and urged her to “work for peace.” At the age of five, she stopped her father from chopping down a tree near their London home, her first ecology action, and in 1970, at the age of 20, she attended the world’s first Earth Day protest in London’s Trafalgar Square.

Argentina at the time suffered under a series of military dictators, and Susi’s father quietly opposed the Junta headed by General Alejandro Agustín Lanusse. When her father died, the tragedy radicalised her, and she embarked “on a personal journey of activism.”

Hosting the film star

Susi worked for Friends of the Earth in London for two years, and in the summer of 1975, she attended the International Whaling Commission (IWC) meeting in London, where she met Greenpeace members Paul and Linda Spong. Greenpeace Foundation in Canada had spent two years planning our first global ecology action, after protesting US and French nuclear weapons tests for four years. We were tracking Russian whalers off the coast of California in a fishing boat, and our campaign depended on confronting the whalers during this London IWC meeting.

Paul and Linda Spong informed Susi about the planned confrontation, and she helped organise London ecologists and media for the coming drama. In June, two days before the IWC meeting would close, we located and blockaded the whalers. The next day, we announced the confrontation by marine radio, and Susi, Paul, Linda, Greenpeace filmmaker Michael Chechik, and a team of activists stormed the IWC meeting with the news.

In 1976, Susi met Greenpeace co-founder Bob Hunter in London. Hunter returned to Vancouver with tales of “the amazing Susi Newborn” in London. He called her “a hard-core, grassroots ecologist who could help lead the next generation of Greenpeace actions in Europe.” Six months later, she arrived in Canada to participate in a campaign to halt the slaughter of infant seals on the Labrador ice floes. Susi told me that the direct action tactics and Earthy spiritual style of Greenpeace appealed to her.

In May 1977, Susi pitched her tent on icy Belle Isle, 32 kilometres off the coast of Labrador, surrounded by ice floes, awaiting the arrival of the Norwegian sealing ships. Susi and David “Walrus” Garrick explored frozen caves and wrote a “Declaration of Freelandsea,” a free-spirited manifesto of ecology.

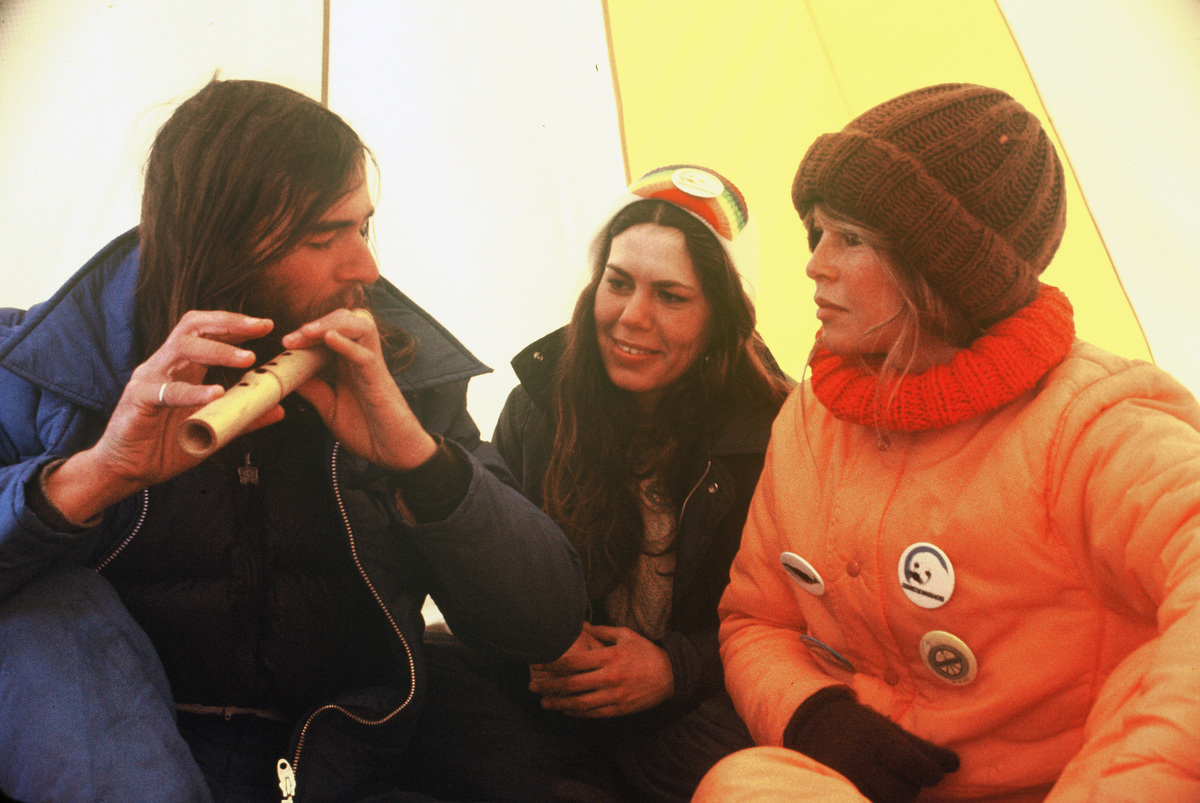

Three days after Susi and the Greenpeace team pitched camp on the ice, French actress Brigitte Bardot arrived to help bring attention to the Norwegian infant seal slaughter. Bardot wrote in her account that she had been “terrified” flying through a storm in the helicopter, and she arrived at the camp stifling tears and clutching her frozen fingers under her arms. Susi made her a cup of hot chocolate, warmed her in the tent, and explained practical tips, such as how a woman could pee at night on frozen Belle Isle. “They give me courage,” Bardot wrote in her journal.

Rainbow Warrior

Back in London, Susi next wanted to disrupt Icelandic whaling. She recruited Denise Bell from Friends of the Earth and set out to find a boat to confront the whalers in the North Atlantic. I sent her a file of photographs from the nuclear, whale, and seal campaigns. Like us in Canada, Susi had no money. She started fundraising, using Michael Chechik’s documentary film of the first two whale voyages, which was aired on the BBC with an introduction by British naturalist David Attenborough. Susi and Denise met Charles Hutchinson from London and Allan Thornton from Canada, and the group opened the first Greenpeace office in the UK at 47 Whitehall Street. Simultaneously, French activist Rémi Parmentier and Canadian David McTaggart opened another office in Paris, where they were protesting French nuclear testing in the South Pacific.

Susi and Denise Bell scoured maritime journals, looking for ships for sale. On the Isle of Dogs, in the Thames Docklands, they found a rusting, diesel-electric, 134-foot trawler that had been converted to a research ship by the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, and Food. The Sir William Hardy was available to the highest bidder. Charles Hutchinson introduced them to the manager at Lloyds of Pall Mall bank. They received a bank loan, secured by the life insurance policies of Hutchinson and Bell. The Department of Trade accepted their bid of £42,725, and they put down a 10 percent deposit, £4,272, on the ship. This was the first ship that Greenpeace actually owned, and Susi sent us photographs of the sad looking trawler that within a decade would become one of the most famous ships of the 20th century.

Newborn, Bell, and an army of volunteers cleaned the ship, stem to stern. Susi recruited her childhood friend Athel von Koettlitz and Australian boyfriend Chris Robinson to tackle the restoration. They clambered down into the pitch-black engine room with a flashlight. The hovel was a rust bucket, and the 800-horsepower engine had not been fired in years. They wiped moisture off gauge glass, tightened loose fittings, and got the two-stroke diesel engine running. Susi and the team removed trawling gear, scraped off rust, painted the ship, and shopped for second-hand parts.

In the fall of 1977, they negotiated with the Ministry to reduce the final price of the Sir William Hardy to £32,500, about £182,000 today. To raise this money, they toured Europe with the documentary, The Voyage to Save the Whales. In the Netherlands, the World Wildlife Fund financed a fundraising campaign. Bob and Bobbi Hunter departed for Amsterdam to accept the money for Greenpeace. On the way, they stopped in London to see the new ship, and there Bob Hunter gave Susi a copy of Warriors of the Rainbow, a book that had inspired Greenpeace in Canada, with a prophecy about how all the people of world — people of the rainbow — would come together to save the Earth from ruin. The crew later agreed to rename the ship Rainbow Warrior. The crew added rainbows to the ship’s deep green hull, a white dove copied from the book cover, and painted Rainbow Warrior at the bow, the vessel’s glorious new name.

Whales and nuclear waste

Susi saw Greenpeace as an integration of ecology, the Gandhian satyagraha she had learned from her father, Quaker direct action, and a deep respect for Indigenous Earth-informed spirituality. She was naturally inclusive and realised that the hard-edged punks of London appreciated ecology as much as the hippies, peace activists, and affluent conservationists. She recruited nuclear campaigner Peter Wilkinson, who had grown up around the South London docks, and had good relations with the dockworker unions, whom he convinced to “turn a blind eye” to the non-union Greenpeace team working on the ship. Susi built alliances with everyone. “Our gut reactions to injustice are the same,” she told her colleagues.

By January 1978, the Rainbow Warrior was ready for its first ecological campaign, and on 2 May, they slipped down the Thames and into the North Sea. The seasoned crew included skipper Nick Hill; chief mate Jon Castle; Peter Bouquet, a mate off a tanker; cameraman Tony Mariner; and Von Koettlitz assisting Chief engineer Simon Hollander. Devonshire nurse Sally Austin served as medic, Hilari Anderson from New Zealand as cook. Bob Hunter and Fred Easton joined the crew from the Greenpeace Foundation in Canada. Remi Parmentier and David McTaggart joined from the Paris office; and Bell, Hutchinson, Thornton and Susi Newborn form the UK core of the crew. Others came from Holland, Scotland, South Africa, Switzerland, and Australia.

Crowds welcomed the ecologists in Calais, Amsterdam, Hamburg, and Aarhus, Denmark, where Susi and the crew showed films from earlier Greenpeace missions. Greenpeace organisations emerged in some of these cities. Susi understood that to spread the ideas of peace and ecology we needed to not only take action, but also build the movement itself.

The Rainbow Warrior crew confronted Icelandic whalers, then put into Reykjavik to release film to the media. Pete Wilkinson joined the crew in the UK and told Susi he had found evidence that the European nuclear industry was dumping radioactive waste into the Bay of Biscay, off Spain. The crew decided to expose the toxic dumping scheme, and pushed south. They would soon blow the lid off one of Britain’s nastiest secrets.

At Falmouth Bay, Susi and Denise Bell returned to London to issue media releases and handle inquiries. Easton and Mariner travelled north to Sharpness, where the nuclear dumping ship Gem sat in port, loading large drums labelled: RADIOACTIVE WASTE.

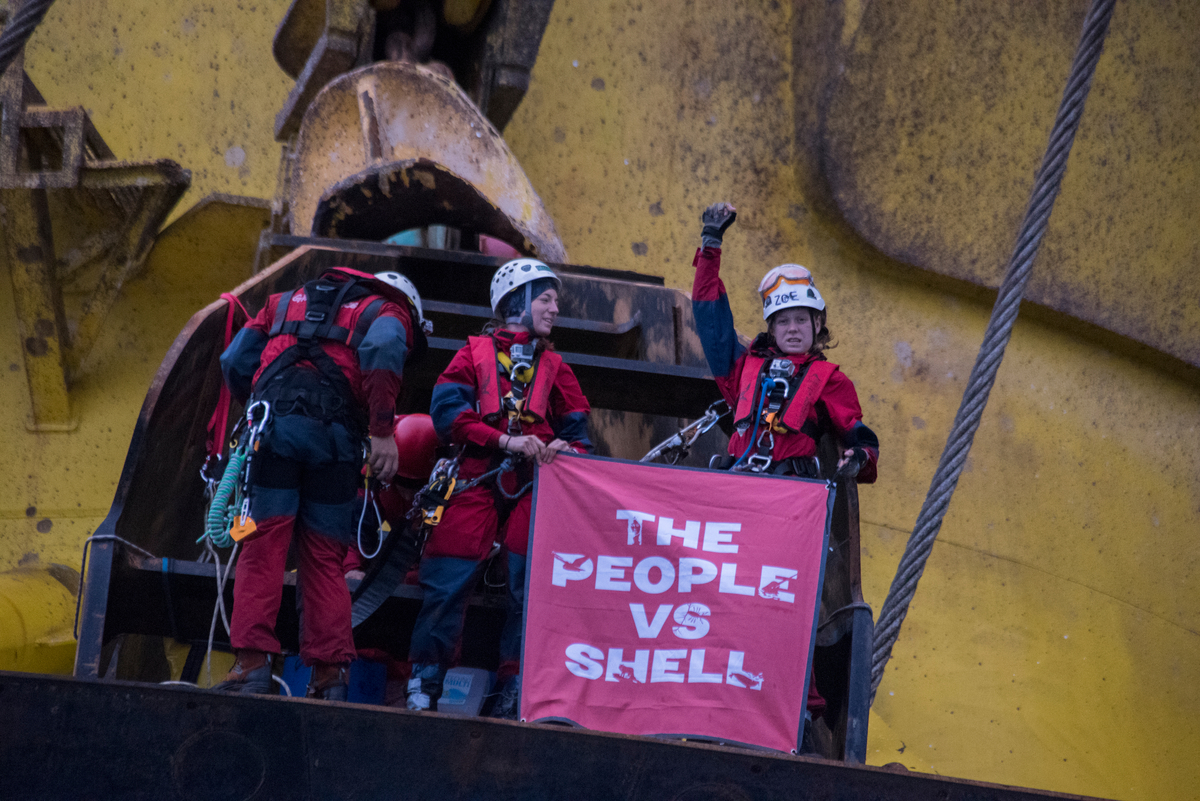

Later, off the coast of Spain, the Rainbow Warrior interrupted the dumping. A 600-pound drum dropped from the Gem and flipped a Zodiac, throwing Gijs Thieme into the water, as the film crew captured the event. Later, in London, Susi and the European media teams released the film and photographs and organised a debate with nuclear industry representatives on the BBC. The activists revealed that each year, approximately 80 kilograms of plutonium-239 had been dropped into the Atlantic trench. In a few weeks, the Rainbow Warrior team had opened a new era of scrutiny for the entire European nuclear industry.

Greenpeace International

For the summer of 1979, Susi and the London activists organised new confrontations with the Icelandic whalers and the nuclear garbage scow Gem. Susi, the alliance builder, offered the Rainbow Warrior to Amnesty International, CND, Greenpeace New Zealand, and to other activists for campaigns. When crews returned from campaigns, Susi later told the New Zealand Dominion Post, “it’s like they’ve been to a war zone. You feel like you’ve gone to some bloody killing field somewhere.” In 2015, she recalled, “I still have injuries from those experiences.”

As Greenpeace became more famous, power struggles naturally arose, and in 1979, Susi fled London to get away from the conflicts. She retreated to the Greek island of Samos, but didn’t rest for long. In Ayios Konstantinos, she heard from fishermen about an annual massacre of Aegean monk seals in the Mediterranean. In her typical fashion, Susi organised “Greenpeace Aegean Sea,” recruited young environmentalist William Johnson, launched a monk seal crusade, and made an alliance with Dr. Keith Ronald from Guelph University in Canada, who brought in the World Wildlife Fund. The ad hoc group successfully ended the marine mammal massacre.

I next met Susi in November 1979, when we gathered in Amsterdam to create an International Greenpeace Council to coordinate the fast-growing organisation. Susi arrived on the Rainbow Warrior with Jon Castle, Tony Mariner, Athel von Koettlitz, Pete Wilkinson, and others from Europe. The council included representatives from Canada, UK, US, France, Denmark, and the Netherlands. New Zealand, Denmark, Australia and Germany joined soon thereafter, and Greenpeace now operates in 55 countries.

Susi was a fearless activist, more interested in the ecological vision of Greenpeace than in organisational manoeuvring or who would have power. During the week in Amsterdam, I met with her frequently, and the talk was always about our next actions and what we might achieve with Greenpeace tactics. Susi was the real deal, an activist to admire and emulate.

Kia ora

Susi moved to the US and received a degree in Human Ecology from the College of the Atlantic in Maine. In 1985, in New Zealand, during a campaign to stop French nuclear tests at Moruroa Atoll in the South Pacific, the French Secret Service bombed the ship Susi had loved and laboured over. The bombing broke her heart. “Not in a month of Sundays,” she said, “would I ever have expected a major European country to blow up a peace boat.”

In 1986, she moved to New Zealand (Aotearoa), where she stayed active in ecology and justice campaigns. In 2003, her Rainbow Warrior memoir A Bonfire in My Mouth was published by HarperCollins.

In New Zealand, in the 1990s, Susi served on the Board of Greenpeace New Zealand. She worked for Oxfam as their climate campaigner, for the NZ Refugee Council, and for the film union. Susi was a poet and a grand storyteller. She loved to talk about her days with Greenpeace and the importance of nonviolent direct action in changing our world for the better.

In the late 1990s, she moved to Waiheke and remained active in campaigns from protecting sensitive ecological regions to supporting Palestinian civil rights. In 2014, Susi helped create a Climate Voter initiative, encouraging New Zealanders to use their vote to make change. The following year, she joined her friend, Greenpeace Aotearoa executive director Bunny McDiarmid, in a march to stop deep sea oil drilling in the region.

In 2022, Susi began treatment for breast cancer. “I know there is something in the world that is creating a giant cancerous tumour,” she said at the time, “that is tearing us apart, commodifying the air we breathe and the water we drink. I also know that this tumour is interspersed with flowers and song birds and the salty waters of the tears we shed.”

Susi Newborn passed away on 31 December 2023, at the age of 73. The Maori community of Waiheke hosted a memorial for her at Piritahi Marae on Waiheke Island, on the tribal lands of the Ngāpuhi and Ngāti Paoa Māori people. Piritahi means, fittingly, “coming together as one.” The community gave her a tangi, a Māori farewell. Friends who worked and sailed and battled with Susi over 50 years, attended and offered fond memories.

“Susi, had a strong sense of injustice,” said McDiarmid, “and never gave up hope it was possible to make change in the world. She believed in the strength of people to make change. She was also really funny, clever and incredibly good company.”

“Susi was brave and fearless,” said her friend Bianca Ranson, “but that was balanced with her kindness and her generosity. Susi showed us how to be fearless and brave and calculating. She taught us how to keep ourselves safe while pushing the line as hard as we could. What she was doing decades ago, if only people had taken that seriously then we’d be in a very different situation now. She was a pillar, a pou, of the island community. What are we supposed to do without her?”

“What I loved in the early Greenpeace years was the feeling that anything could happen anytime, anywhere,” wrote Rainbow Warrior photographer Pierre Gleizes Nicéphore. “On board, life was never dull, and Susi was part of that story from day one.”

“Susi and I have been the best of mates since we met in 77,” said former Rainbow Warrior cook, Hilari Anderson. She called Susi “a feisty sister Warrior.”

I corresponded with Susi and spoke with her by phone many times while she was in New Zealand. She always signed off with “Kia Ora,” a Māori greeting of wellbeing that means “have life.”

Indeed. Kia Ora, dear Susi.

Links, Sources:

A Bonfire In My Mouth: Life, Passion And The Rainbow Warrior, by Susi Newborn, HarperCollins, 2003

Susi’s Great Unleashing, Newborn blog

We say goodbye to Susi Newborn, co-founder of Greenpeace International and Rainbow Warrior, Greenpeace Chile

The legacy of Susi Newborn, Aida Cuenca, Climatica Lamarea, 3 January, 2024

Susi Newborn, an original warrior, finally rests, Virginia Fallon, NZ, The Post, 6 January, 2024

Rainbow Warrior: Fight the Power, Director: Edward McGurn, UK, France, DOC NYC, 2023