New Zealand is used to singing its own praises on environmentalism. But when it comes to protecting the ocean, the greenwash is starting to peel.

Earlier this month, amidst little fanfare, the Department of Conservation released a disturbing report that illustrates the sobering environmental cost of New Zealand’s commercial fisheries. It showed that 58 protected turtles were caught over the 2020-21 fishing year, most of them critically-endangered leatherback turtles.

In Hawai’i, which has strict annual limits for turtle interactions, the whole fishery shuts down if a total of 16 leatherback turtles are caught. Last year they reported just 3 interactions with leatherbacks. No such hard caps exist in New Zealand.

The turtle report made the evening news but then became just another shameful statistic on how commercial fisheries here are endangering marine life, and letting the side down internationally.

It illustrates what people on the front lines of ocean protection have been saying for a long time: that there is now a massive gap between how New Zealand sells itself on the world stage, and the actual level of action our government is taking to protect the ocean.

Minister for Oceans and Fisheries David Parker recently claimed we’re one of the best managers of fisheries in the world, and that the government is concerned about biodiversity protection overall. But the numbers dispute those claims.

In the same year commercial fishing caught 58 protected turtles, the New Zealand bottom trawling fleet was the only one trawling seamounts in the South Pacific. That’s the kind of trawling where large weighted nets are dragged over vibrant and fragile coral forests, hotspots for biodiversity that provide feeding grounds, breeding spots and shelter for a huge array of marine life. Even humpback whales are known to use seamounts for navigation and for feeding.

“Even humpback whales are known to use seamounts for navigation and for feeding.”

Other countries and jurisdictions have closed seamounts to bottom trawling, including Chile and Palau. Seamounts in a large area of the Atlantic Ocean and in the Antarctic are also protected, because of the detrimental impact trawling has on deep sea ecosystems.

The latest available figures from the Ministry for Primary Industries show that over 9,000kgs of protected corals and sponges were pulled up in New Zealand waters over six months between October 2021 and March 2022. That number is bad enough, without factoring in that what comes up in the net is a fraction of what is destroyed on the seabed.

Like all things in the deep, these coral reefs are often ancient, slow-growing and include unique and protected species. Despite these being protected species, commercial fisheries are given leeway to destroy them with impunity under the Wildlife Act.

In the middle of a biodiversity crisis, the scale of these losses is indefensible.

To turn this around, the government needs to be bold and ambitious. They need to prioritise ocean protection, both at home and abroad. They need to take decisive action to live up to our green reputation by showing that we are a country that protects the ocean and prioritises the planet over commercial profit.

Over the next week there will be a chance for New Zealand to do this, as negotiations for a Global Oceans Treaty resume at the United Nations in New York. If done correctly, this Treaty would allow for fully protected areas to be created in international waters across our blue planet – free from destructive fishing and mining.

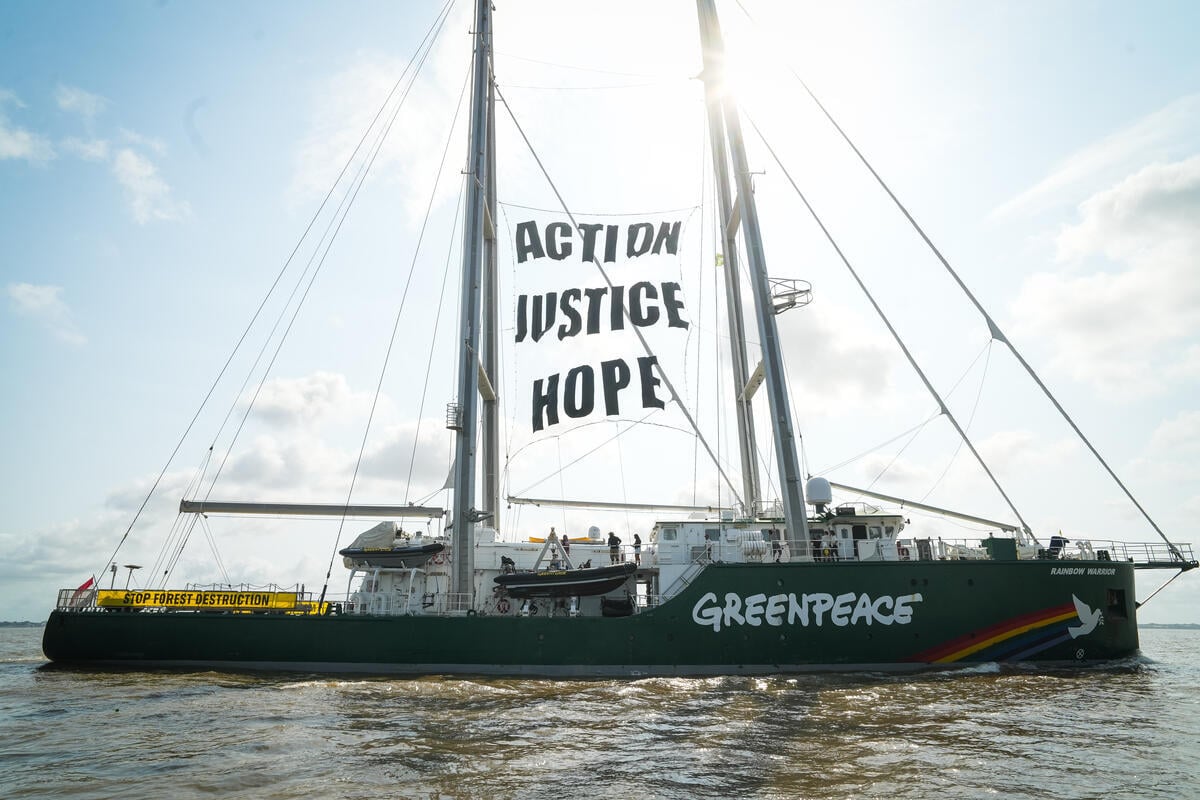

Greenpeace USA activists project a Global Oceans Treaty message on the Guggenheim in New York.

Putting at least 30% of international waters off limits to destructive activities like commercial fishing is what scientists say we must do, if we’re to have a healthy planet for the future. New Zealand’s representatives agree with this in theory, but are falling at the last hurdle.

For these protected areas to do what they’re meant to – safeguard important biodiversity hotspots and marine life – it is essential the right people are in charge of putting them in place. Right now, New Zealand’s representatives support existing groups like fisheries management organisations being left to implement protected areas, the same bunch that have caused the ocean crisis we face.

What is clear from the statistics in New Zealand and around the world, is that commercial fishing has a huge impact on the ocean and the creatures that call it home. To protect them, groups whose primary mandate is commercial fishing cannot be the best team we have.

We are a nation surrounded by ocean, spoiled by natural beauty and with deep cultural ties to the waters around us. Faced with the biggest conservation effort in history, it’s my hope that this week, those representing New Zealand on the world stage do more than talk us up, and take bold action to protect the blue planet we call home.

- Ellie Hooper is the ocean campaigner at Greenpeace Aotearoa