Jacinda Ardern’s April 2018 ban on new oil exploration permits put New Zealand’s vast ocean territory off limits to new oil and gas exploration except for a few areas where permits were released before the ban came into effect.

It was globally significant and arguably remains the most impactful climate action the previous Labour Government made in either of its two terms.

New Zealanders are proud of the ban, and thousands of people fought long and hard to achieve it. They won’t let it be overturned without a fight.

But now, with the new coalition Government led by Christopher Luxon, who has promised to repeal the ban and open up New Zealand’s waters to oil exploration once again, we face the threat again.

Searching for more oil and gas is a significant threat to the climate – scientists tell us that to have any hope of stabilising the climate, the world cannot afford to burn even known reserves, let alone new ones.

In the past year here in Aotearoa, the climate crisis has become increasingly self-evident.

In early 2023, Cyclone Hale smashed the Coromandel, and the deadly Auckland Anniversary Day storm caused widespread damage that you can still see today. Then, close on its heels came Cyclone Gabrielle, which proved to be our deadliest cyclone since 1968 – and the costliest tropical cyclone to ever hit the Southern Hemisphere.

As predicted, climate-driven weather events are becoming more frequent and more extreme, and that’s in large part driven by burning fossil fuels. The world has to stop burning oil and gas, not start looking for more.

The risk of oil spills with oil and gas exploration

On top of the potential climate impacts of oil exploration, there’s also the additional risk of oil spills.

In 2010, BP’s disastrous Deepwater Horizon blowout in the Gulf of Mexico focused the world’s attention on the devastating environmental and economic consequences of a deep sea oil drilling disaster.

One of the reasons the Deepwater Horizon blowout was so catastrophic was that it was in deep water, which made it extremely difficult to cap.

Much of New Zealand’s ocean territory is also very deep water where, for exploratory drilling, the risk of disaster is very real.

Exploratory drilling is the riskiest phase of drilling

The cost of drilling in deeper water is not linear with depth; it increases exponentially. The risk of a blowout also increases with depth. The challenges faced are significant and complex: from the rig to the deepest section of the well.

In New Zealand, the current deepest production well is only 125 meters below sea level, but new oil exploration could happen in waters ten times that depth or more.

When an oil rig is used to explore for new reserves, very little is certain about the type of hydrocarbons that may be present or the pressure of a potential reservoir prior to the first well being drilled. They just don’t know what they’ll find.

The source of the Deepwater Horizon disaster was an exploratory well.

The question of oil spill response preparedness

New Zealand’s ocean territory is vast, and many sites where oil exploration could happen are remote. For example, OMV’s Tawhaki-1 exploratory drill site in the Great South Basin was 85 nautical miles offshore from Dunedin – twice the distance the stricken Deepwater Horizon was from shore. And it’s in a region with very little exploration infrastructure where the weather and the sea conditions can be wild.

The Environmental Protection Authority’s decision to consent to the project seemed fatally optimistic when they said “…we are satisfied that Maritime New Zealand and other agencies have the plans, structures, processes, access to equipment, and financial resources to respond to an oil spill event should one occur.”

The Rena oil spill showed us how unprepared New Zealand is for such an emergency, and the oil spilled there was only a fraction of what could be spilled by a deep sea drilling blowout.

The Deepwater Horizon response had around 4,100 kilometres of containment booms, and deployed 47,000 people and over 6,000 vessels including dozens of purpose-built response ships of up to 70 meters in length.

Maritime New Zealand has just three 11-metre flat-bottomed inner harbour aluminium boats to service the whole country.

The EPA went on to say:

“We accept that the overall environmental effects on the biological environment, existing interests, and cultural values from a significant oil spill event could be extensive”

No shit. The deepwater horizon blowout disgorged 650,000 tonnes of oil.

How bad would a deep water oil spill be in New Zealand waters?

It would be bad, really bad. But it’s hard to say exactly how.

OMV provided some oil spill modelling for its Great South Basin drill site, but an independent analysis commissioned by Greenpeace found it to be badly lacking. OMV has since rescinded its licence, which means the Great South Basin is now off-limits for oil and gas exploration under the current rules – a huge win for the movement against oil and gas exploration. This is the kind of progress that Christopher Luxon is proposing to reverse.

OMV’s spill modelling assumed any blowout would take a maximum of 21 days to cap, but the Deepwater Horizon blowout lasted 87 days.

Without adequate oil spill modelling, we can’t get an accurate idea of what the impact of an oil spill in deep water could be. But in 2013, Greenpeace commissioned modelling of an oil spill at Anadarko’s ‘Caravel Prospect’ drill site off the Otago Coast.

It painted a terrifying picture of what could happen if a blowout were to occur there.

A possible oil spill scenario

From day 1, thousands of barrels of oil could flow into the ocean every day.

To stop the spill, a relief well would need to be drilled. Rigs capable of doing that in deep water are highly unlikely to be available in New Zealand to do the drilling, so an available rig would have to be located and contracted from overseas.

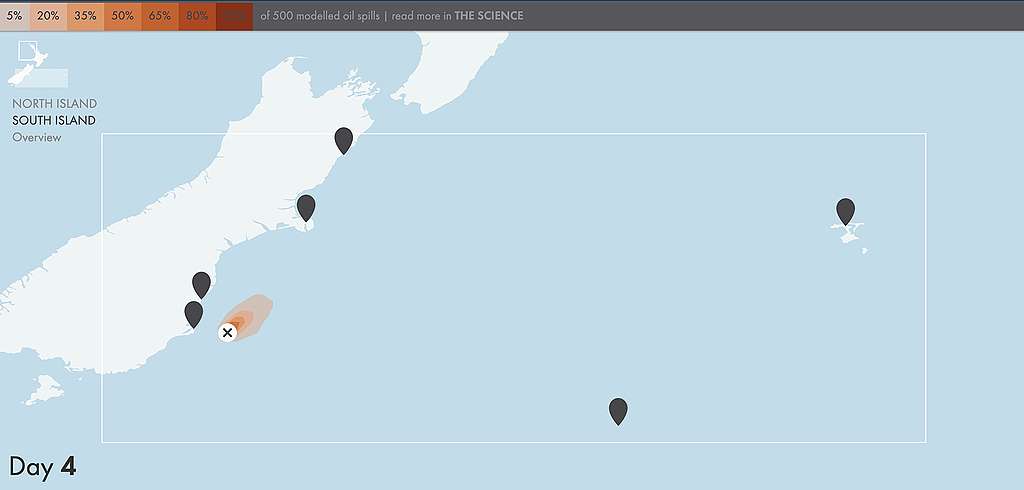

On day 4, the spill response is overwhelmed.

Maritime New Zealand is responsible for responding to the spill. After only four days, it is likely that their dispersant supplies will have run out and that their three small boats, if they can even make it to the area at all, will have been overwhelmed, any additional help will need to come from offshore.

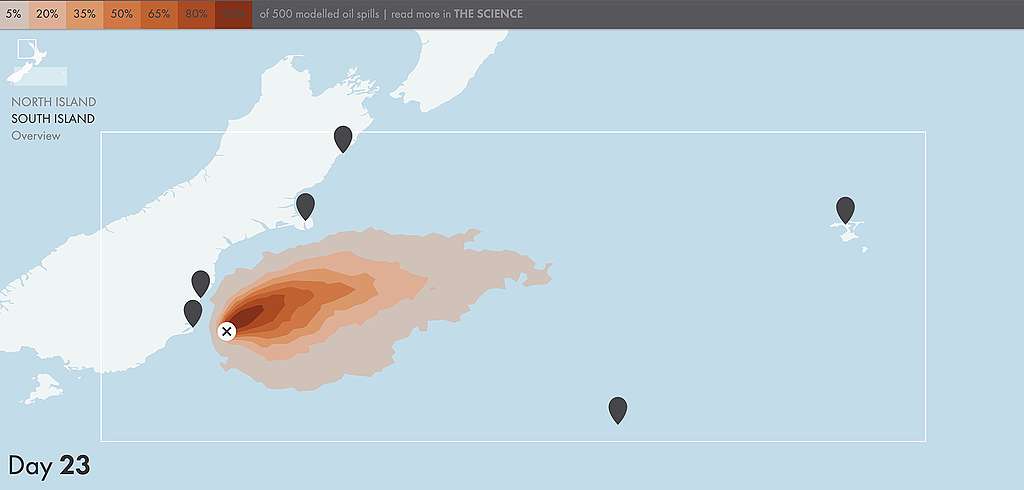

On day 23, the relief rig finally arrives at the drill site.

Fortunately, in this scenario, an uncontracted relief rig capable of drilling in deep water was available on Australia’s North West Shelf. After the long journey to New Zealand, it has finally reached the drill site.

The complicated task of drilling into the damaged well to perform the necessary kill operations and stop the blowout can now begin.

On day 35, Oamaru penguins are on the frontline of the oil spill.

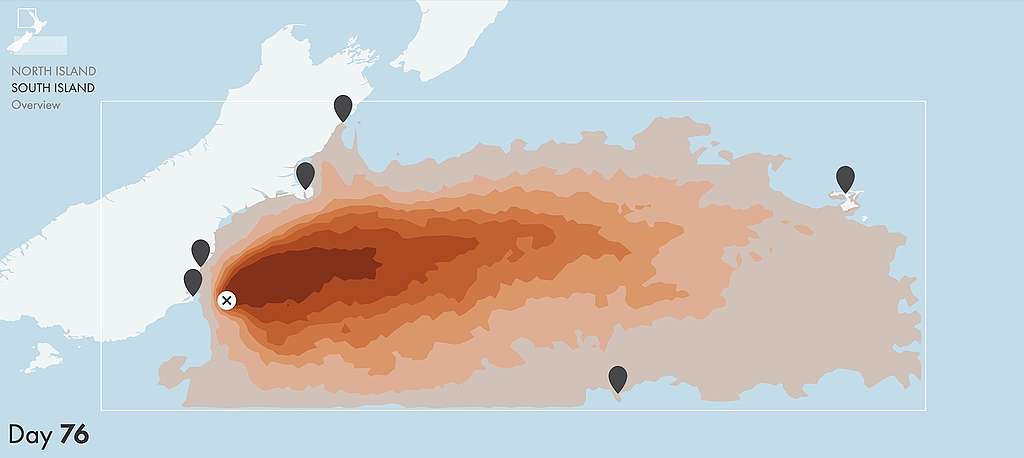

The probability modelling map shows the likelihood that a particular area will be impacted by more than 1g/m2 of oil. This threshold is the amount of oil that would require a beach clean-up.

In the worst case scenarios (a probability of 5%), Oamaru’s local penguins may not only have to contend with a dangerous oil slick out at sea, but the oil may also wash up on the beaches where they come ashore each evening.

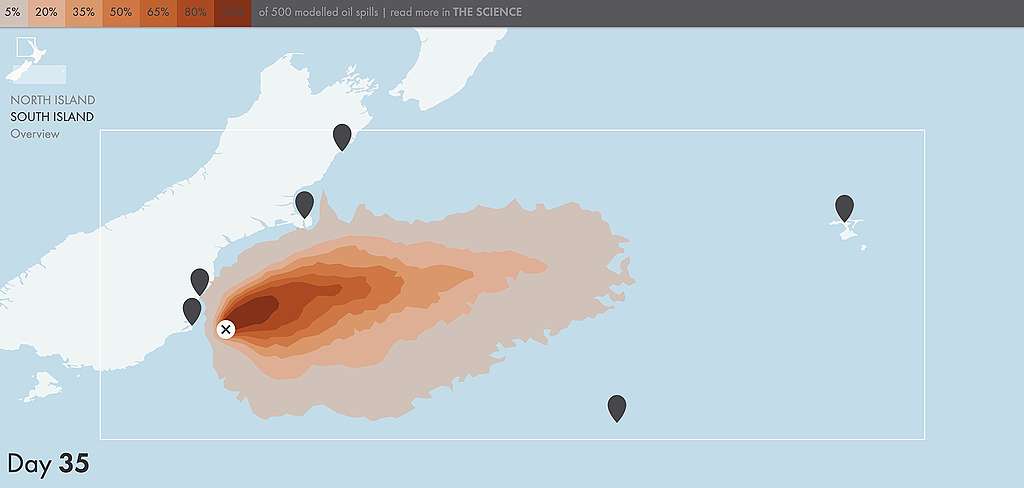

On day 70, Kaikōura’s whales are under threat.

Tourists flock to the coastal town of Kaikōura to see sperm whales. However, after 10 weeks, a vast area of their preferred habitat off the Eastern coast of the South Island could be impacted by the oil spill. In the worst case scenarios (probability 5%), even the beaches of Kaikōura will need to have oil cleaned from them.

On day 76, the relief well is completed.

Relief well operations took relatively little time in this scenario and the damaged well is finally intercepted and plugged. Oil is no longer spilling into the ocean, but a large quantity is very likely to remain on the sea surface.

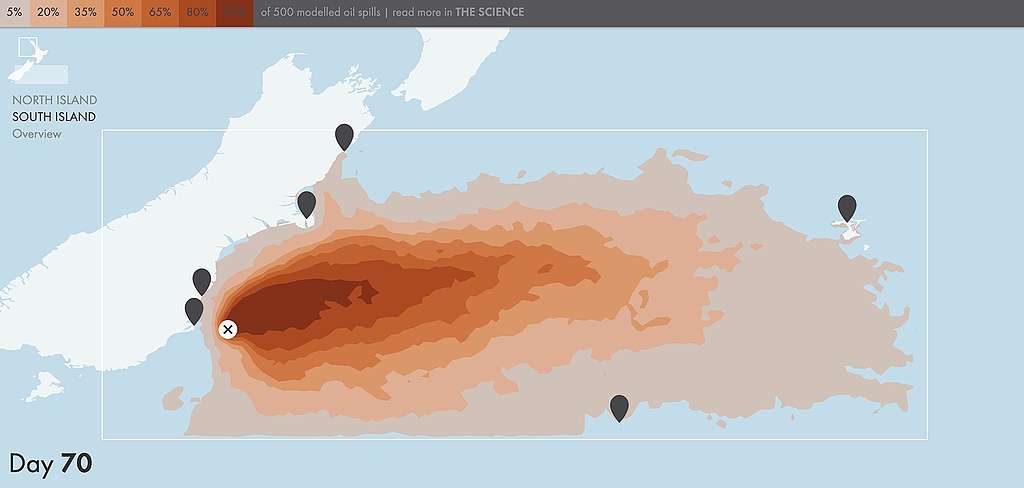

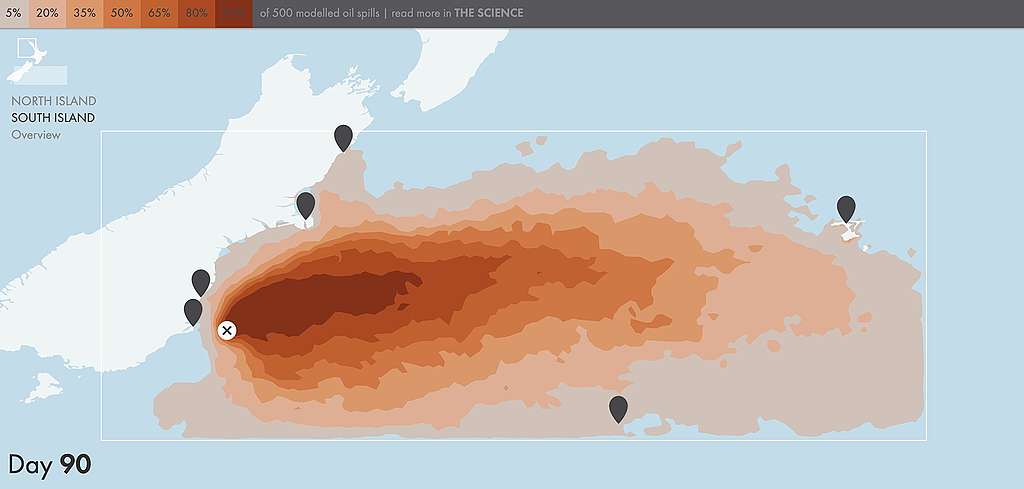

On day 90, there is a wide impact plume.

Despite hundreds of kilometres separating the Chatham Islands from the site of the blowout, a spill could now impact these islands. After three months, the worst hit parts of the Chatham’s have a 35% probability of oil affecting the shoreline.

Combined with the impacts on the prime oceanic foraging grounds of the Chatham Rise, a spill could have disastrous consequences for the unique seabird and marine life of these islands.

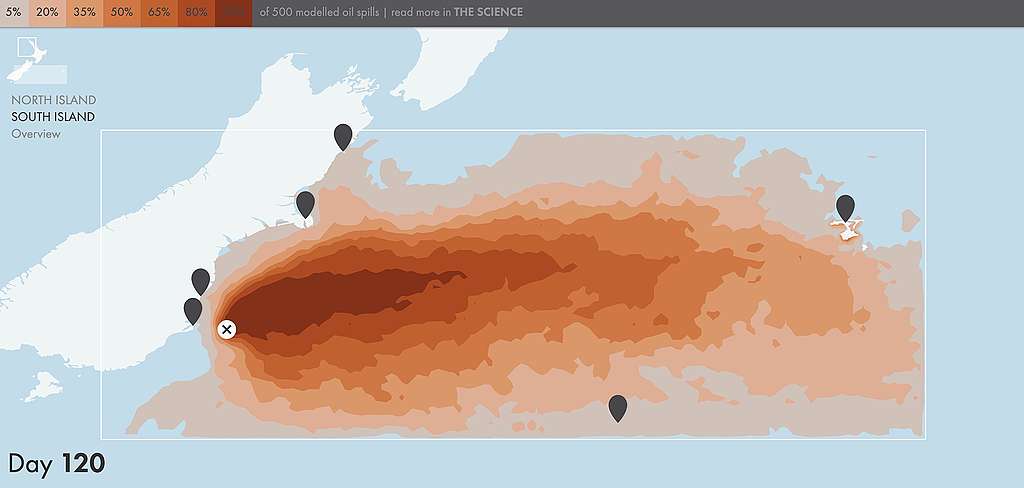

On day 120, there are ongoing impacts.

Although the blowout was stopped over a month ago, oil will very likely continue to drift across the ocean and wash up on the coast. Sadly, this is not the end of the disaster, as the effects of the spill will likely endure for years to come.

Can we apply this modelling to other possible drill sites that Christopher Luxon could offer up?

Yes and no.

Back in 2012, the exact drilling location for Anadarko’s Caravel site, which we modelled, was estimated from statements made by Anadarko to its investors because the precise drilling locations were only publicly released after our study was completed. Because of that, we tested whether varying the precise release site would change the probabilistic maps. It resulted in only minimal alteration to the overall impacts.

But New Zealand’s ocean territory is vast. In different places, there are varying currents and winds, and there are potential drill sites closer to the shore as well as further away. So it’s impossible to say for sure what the impact of spills from each potential site is without detailed modelling of each.

But, suffice to say, oil spills are toxic to marine life, and a big blowout could leak large amounts of oil into the ocean for months. It would be disastrous no matter where it happened.

Oil spill cleanup difficulties

One of the tools in the oil spill response plan is often a ‘dispersal agent’ that can be spread over the water. For example, the controversial ‘Corexit’ was used following the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

Chemical dispersants disperse the spill into finer droplets so that it more quickly mixes into the ocean. Nearly 2 million gallons of dispersants were used during the Deepwater Horizon response. This is equivalent to 9 megalitres, or nearly 4 olympic-sized swimming pools worth of dispersant alone. It works to some extent, but Corexit has been shown to greatly increase the toxicity of oil.

How many people does Maritime New Zealand have available to respond to an oil spill? The Deepwater Horizon response mobilised 47,000 people and it’s hard to believe that Maritime New Zealand has anywhere near that number.

Will containment booms be available, and if so can they expect them to work in the wild waters off New Zealand’s coastline? Within weeks of the Deepwater Horizon spill, BP deployed over 4,100 kms of containment booms. Despite this, serious questions were raised about the efficacy of the technology – the vast majority of oil spilled in the Gulf of Mexico was never recovered. Indeed, together with burning, booms and dispersants, estimates are that they only removed 16% of the spilled oil.

What vessels does New Zealand have available to deal with a spill?

In the Gulf of Mexico, BP’s Deepwater Horizon disaster required the use of nearly 900 oil skimmers and around 6,000 vessels in total. Maritime New Zealand maintains the capacity to respond to spills of up to 3,500 tonnes and has a total of three ‘Oil Response Vehicles’. Basically, three inshore harbour capable tinnies. They are located in Northland, Auckland and Wellington.

What would be the plan for dealing with harm to New Zealand’s wildlife in the event of a spill?

New Zealand and our offshore islands are home to 25% of the world’s breeding seabird populations. An estimated 80% of New Zealand’s native biodiversity is found in the sea.

The 2010 Deepwater Horizon Disaster has been described as the worst environmental disaster in the history of the United States.

BP has said the Deepwater Horizon cost it US$62 billion. In New Zealand, a spill at even a fraction of this scale has the potential to devastate our environment and economy.

Aside from the risk to the climate, these are risks that are not worth taking.

Sign the open letter to the oil industry – We will resist oil exploration

Sign on