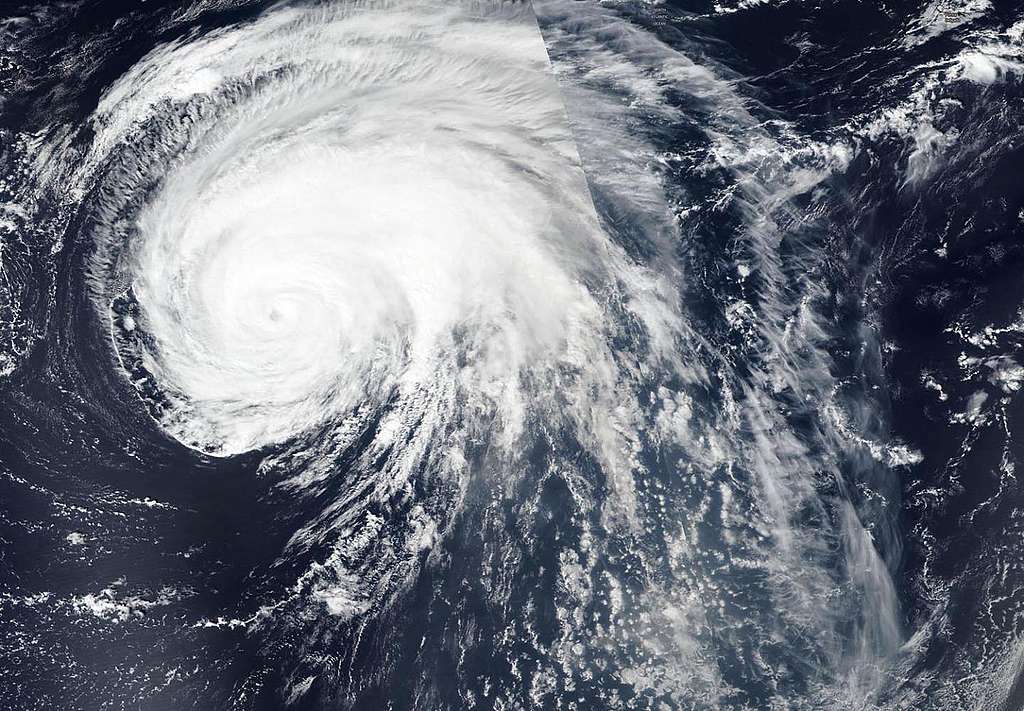

NASA-NOAA’s Suomi NPP satellite passed over Hurricane Lorenzo twice in the Northeastern Atlantic Ocean to obtain a full picture, stitched together, of the large storm. © NASA Worldview, Earth Observing System Data and Information System (EOSDIS)

Over the past few days, we have witnessed the formation of an extreme weather event of unprecedented intensity in the northeastern Atlantic.

Why unprecedented? It is the first time that a hurricane in this part of the Atlantic has reached this magnitude. In a remarkable burst of rapid intensification, Hurricane Lorenzo intensified to reach Category 5 status late last Saturday. This is the highest category on the Saffir-Simpson scale. It became the Atlantic’s second Cat 5 storm of the year, the strongest hurricane ever observed so far east in the Atlantic, and one of the northernmost Cat 5s on record with sustained winds of 250km per hour.

Hurricane Lorenzo. © National Hurricane Center

Lorenzo has now cleared the Azores and is moving towards the British Isles as a post-tropical cyclone currently with sustained winds of 80mph and higher gusts. The US National Hurricane Centre describes Lorenzo as “a very large cyclone. Hurricane-force winds extend outward up to 150 miles (240 km) from the center and tropical-storm-force winds extend outward up to 390 miles (630 km).”

Hurricanes of such intensity may seemingly be rare but they appear to be becoming a more frequent meteorological phenomenon. Matthew (2016), Irma, Maria (2017), Michael (2018), Dorian and now Lorenzo in 2019: the consecutive period of 2016- 2019 is the longest sequence of years in which at least one Category 5 event occurred. 2017 and 2019 are two of only seven years since 1851 (when reliable records began) in which more than one Category 5 Atlantic hurricane occurred.

What are hurricanes?

Hurricanes form in areas of warm (tropical) water. As the warm ocean air rises pressure changes are generated, creating largely closed air circulation systems in the atmosphere – strong winds that rotate counterclockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere.

When fully developed such systems are known as a “cyclone” in the Indian Ocean and the South Pacific Ocean, a “hurricane” in the Western Atlantic Ocean and the Eastern Pacific Ocean, and a “typhoon” in the Western Pacific Ocean.

How does climate change affect hurricanes?

The scientific community is working to understand the ways in which global warming affects hurricanes and tropical storms, including its influence on wind patterns. There is no scientific consensus on whether the number of hurricanes will increase in the future. While actual numbers may remain much the same, warmer seas can generate more violent hurricanes which intensify more quickly and warmer air can hold more moisture leading to increased rainfall. There is some evidence that hurricanes may move more slowly, increasing wind damage and rainfall in affected areas.

It makes no sense to stand idly by waiting for the next hurricane and equally, it makes no sense to continue emitting greenhouse gases that cause the warming of the ocean, which in turn helps generate and intensify hurricanes.

We have to stop feeding this climate emergency before it’s too late. That is why it is essential to accelerate the energy and ecological transition to reach zero emissions by 2040 in all countries, leaving no one behind.

Cecilia Carballo is the Programme Director for Greenpeace Spain.

Join our call on the New Zealand Government to make climate crisis its nuclear free moment by taking the climate emergency seriously, with real action now.

Take Action