Wind energy plays a crucial role in reducing carbon emissions and transitioning to cleaner sources of power. When implemented correctly, wind installations benefit local communities and garner their support.

But, when wind developers handle things poorly, they can end up upsetting local communities, causing delays, and negatively affecting the reputation of wind technology. This is what has happened with Hiringa Energy’s green hydrogen project in Taranaki.

Community support and cultural considerations

In Denmark, the success of wind energy has been attributed to community wind ownership. This approach not only gained support from local communities but also supported the widespread roll-out of state-funded development of wind technology.

Here in Aotearoa, working with local Māori must be a bottom line for the legitimacy of new energy infrastructure. As well as a moral imperative, iwi consent and alignment is consistent with upholding Te Tiriti o Waitangi. The quality of the relationship between developers and iwi, and the Crown and iwi, is the touchstone for success. Without iwi and wider community support, the headwinds against the technology slow our ability to transition away from oil, gas and coal. That’s why doing new wind in a way that is right by the locals is vital for the success of the whole clean energy project.

Hiringa Energy’s hurried hydrogen urea project

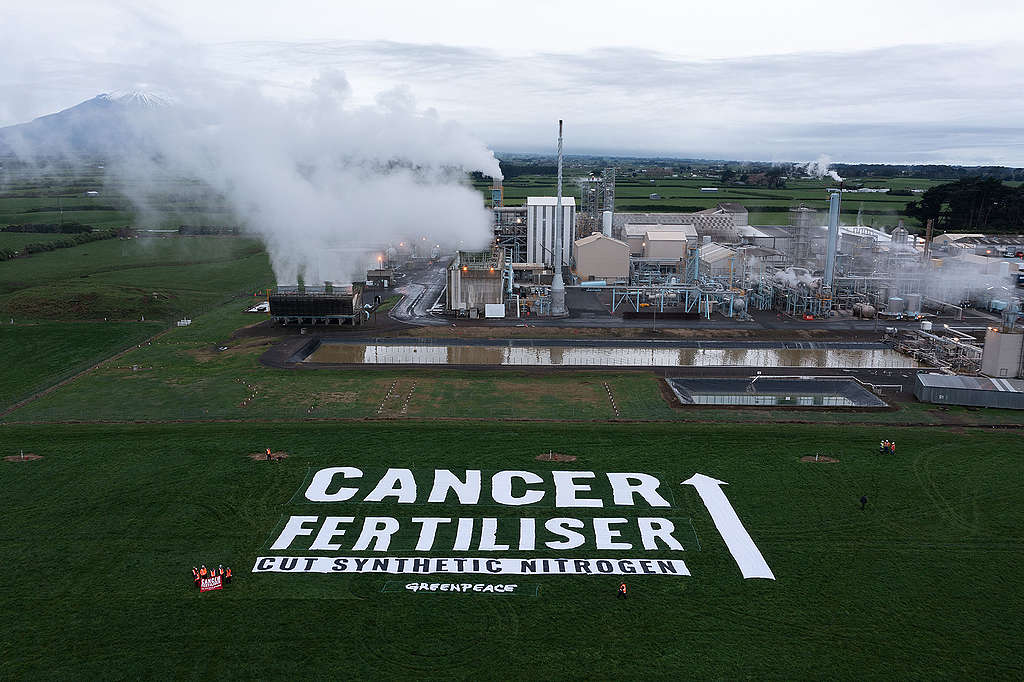

Here is where newcomers Hiringa Energy and stalwart agrichemical giant Ballance Agri-nutrients are potentially causing lasting problems in their rush to fast-track the use of wind for fertiliser manufacture.

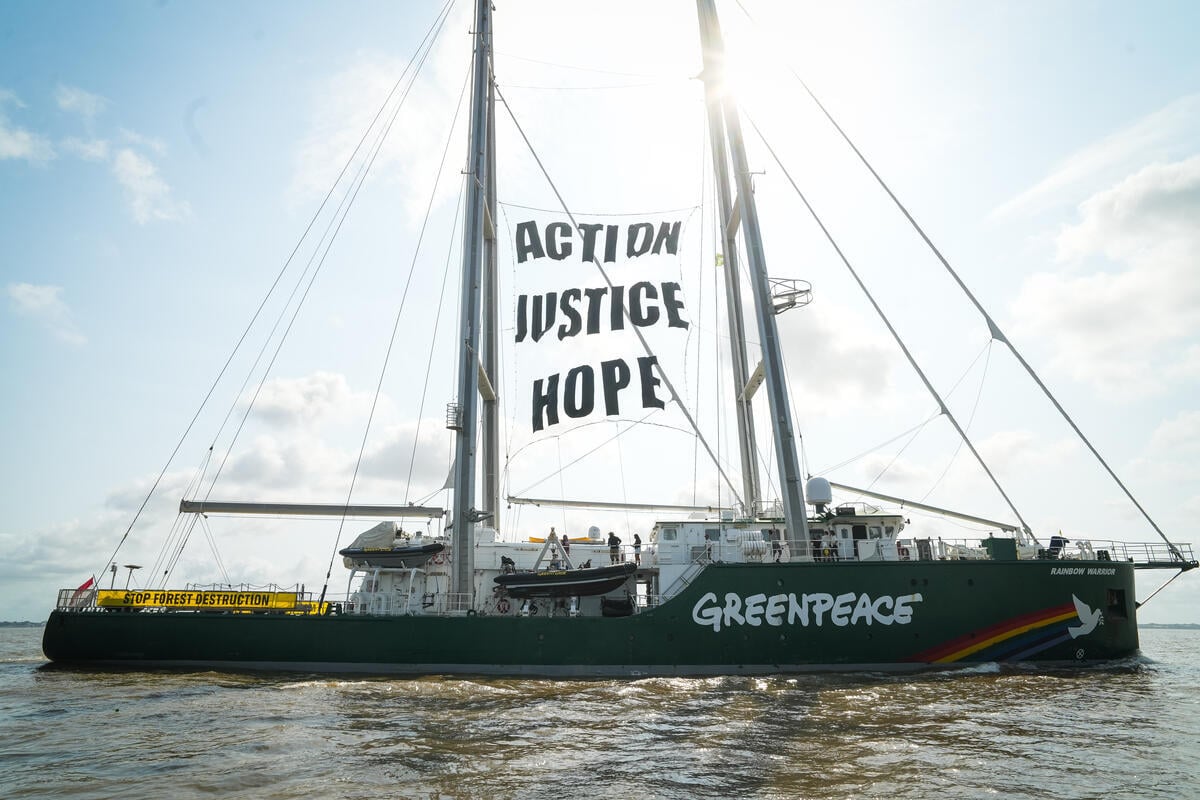

Hiringa Energy have managed to determinedly rub the locals the wrong way and ended up head-to-head in court with a number of the hapū of Taranaki iwi Ngāruahine, and also Greenpeace.

The reputation of wind energy at risk

Hiringa Energy and Ballance Agri-nutrients are giving wind energy a bad name in one of the regions where important opportunities exist to use wind as a means of transition away from oil and gas.

Hiringa Energy’s hasty pursuit of consent rights without adequate public scrutiny during the COVID-19 pandemic has hindered meaningful engagement with iwi. The co-opting of a Māori name for their company – described by Ngāruahine elder Mere Brooks as “brownwashing” – and alignment with one of the nation’s top agrichemical polluters – Ballance – betrays a company wanting the sheen of green without the substance.

By choosing not to move the wind turbines closer to the coast, which was what Ngāruahine preferred, Hiringa Energy created a situation where people no longer saw wind energy as aligned with the priorities of the community. Instead, it became yet another affront and act of disrespect against Māori as part of the litany of Taranaki land confiscation history – a point that hapū lawyer Natalie Coates powerfully outlined to the Court.

Importance of transitioning away from making urea

In the Court of Appeal last May, Hiringa’s lawyer described the company’s founders as formerly of the oil and gas industry and now seeking a new path in clean energy. Their fast-tracked project is billed as a green energy project because it promises to move from creating hydrogen as fertiliser feedstock to using the hydrogen for heavy transport.

If Hiringa is so committed to transitioning from utilising their hydrogen for fertiliser to using it for heavy transport, why won’t they agree to locking in a five-year commitment to do so as part of consent conditions?

The consenting panel who reviewed the project and decided it was worthy of being fast-tracked said that this transition over five years was “crucial” to their decision. It is the Greenpeace case that the panel erred in law by not locking in this commitment, and that is why we challenged Hiringa in Court.

Clean energy for the collective good

Hiringa has the temerity to say that Greenpeace – in challenging their fertiliser expansion plans – is opposed to clean energy. Far from it. We need clean energy but it needs to be implemented with a focus on the collective good – as a solution to climate change and the greed and harm caused by colonisation, industrial agriculture and fossil fuel energy – not just another way to make a buck at the expense of local people and the environment.