Ko tēnei te wiki o te reo Māori. It’s Māori language week, and in fact some of us are celebrating not just the week but #MahuruMāori.

Personally, I’m challenging both myself and my colleagues by spending two hours each day at work speaking Māori only, for the entire month of Mahuru. I don’t translate what I say, I just show a bit of patience.

So far, my non-Māori or non-Māori speaking colleagues have leaned into the discomfort without any issues or reservations.

They’ve enjoyed experiencing something that native English speakers rarely have to, that non-English speakers very often have all over the world. Using a dictionary, context clues, body language and an open mind, we’ve had hui and work-related conversations very successfully over the past week. They’ve embraced a bilingual workplace and created a space to which I can bring my entire self, a safe place for me to push my reo journey a little further today than yesterday.

As a wahine Māori still in my learning stages, I use reo sometimes, even if it’s just simple kupu (words) or whakataukī (proverbs). Of course, that includes my work life and sometimes it’s in these Māori values and concepts, whakataukī and indigenous ways of being that best describe where I sit with regard to our environment and Papatūānuku.

That includes specifically plastic pollution and where I believe the solutions are, as the Plastics Campaigner at Greenpeace Aotearoa.

Te reo Māori and the environment

Lots of people get in touch and I’m asked often, “what do Māori values have to do with plastic pollution? Why do we have to hear about Te Reo me ona Tikanga, or the Treaty? Why is matauranga Māori (indigenous knowledge) always talked about as the answer? We just care deeply about the environment, and race doesn’t matter.”

These are great questions, and it’s an important discussion for all of us. Constructive and provocative kōrero about the position of tangata whenua and what it means for the wellness of our country, our planet, and climate is one of my favourite things to participate in, because it gets to the heart of why I’m an activist for Papatūānuku.

Our language, or reo, doesn’t exist on its own. It’s part of an ecosystem that includes whānau, hapū and iwi; tupuna, pakeke, rangatahi and nohinohi; tikanga, whanonga; tika, pono, aroha. That ecosystem is what it is to be Māori – on one level te wiki o te reo Māori is about revitalisation of our language, and on another is part of a bigger movement to revitalise our identity and lift our people. It needs support and nurture so it may thrive once again.

If you were to ask me what the solution is to care for Papatūānuku and help safekeep the finite treasures she births; if someone told me they wanted to protect our moana but needed guidance … I’d answer that it depends on those who’ve been here exercising kaitiakitanga longer than anyone else, being able to give guidance. But for a very long time Māori have not been able to be wholly Māori, in all spaces, at all times, in all ways.

In the rohe of Whanganui river, there’s a famous whakataukī which ends: ‘Ko au te awa, ko te awa ko au.’ It translates to, ‘I am the river; the river is me.’ This demonstrates how nature relates to our existence.

You may already know that when Māori introduce themselves with a pepeha – a speech that grounds us to our ancestral lands – and rivers, beaches and mountains are the first markers of our identity. When the awa or river dries up, or is so polluted that it can no longer support life, what becomes of our identity then?

Similarly, we have stories that speak to our history and creation marked by taonga species that are integral parts of our whakapapa. Birds, marine life, insects describe and determine who we are and how we live.

Holding on to Taonga

Our campaign to ban the bottle talks about the terrible story of a toroa at Te Tairawhiti that died from starvation after swallowing a water bottle whole. Our toroa are at great risk from plastic pollution and particularly for hapū and iwi for whom toroa are revered taonga from stories about how they came to be, plastic pollution is also a risk to their people.

I’m profoundly concerned about what it all means when these precious parts of our whakapapa might cease to exist. I imagine we might also cease to exist, at least not as our tupuna existed and not as they intended for us to exist, either.

Tangata whenua have inhabited this land for hundreds of years. Māori traversed the motu by foot, lived off the land and moana and had a reciprocal relationship with Papatūānuku. In the Māori worldview, people aren’t separate from the environment, we are part of it and wellness is interconnected, interdependent.

Over these hundreds of years, Māori became experts of the whenua, the moana and all the life it held, exercising kaitiakitanga and care with foresight, preserving and future proofing. Creating customs and systems that sustain all life.

A pathway forward

If we want justice for our environment, our biodiversity, our planet and climate, we must change the systems and power structures that have been in place for the past 200 years, enabling and encouraging this destruction. Shortsighted colonial worldviews have prioritised quick profits for some over the collective wellbeing of all, including nature. These changes will be new and feel very foreign to many of us, but we can expect something beautiful to happen if we are open to being guided by kaitiakitanga and matauranga tuku iho – traditional, expert knowledge.

Today, while we still hold that knowledge and expertise and those instincts lay deep within us, events since the arrival of Europeans have limited and continue to limit rangatiratanga for Māori. Our ability to live wholly and access that ‘ecosystem’ of language, whānau, hapū, iwi, tikanga, values, te Ao Māori, has been systematically restricted with colonial policy and is fraught with trauma that has been felt through generations.

We know a healthy ecosystem needs all its parts. To access these inherent instincts and knowledge systems, to practice our customary ways to protect and sustain, we need our whole selves.

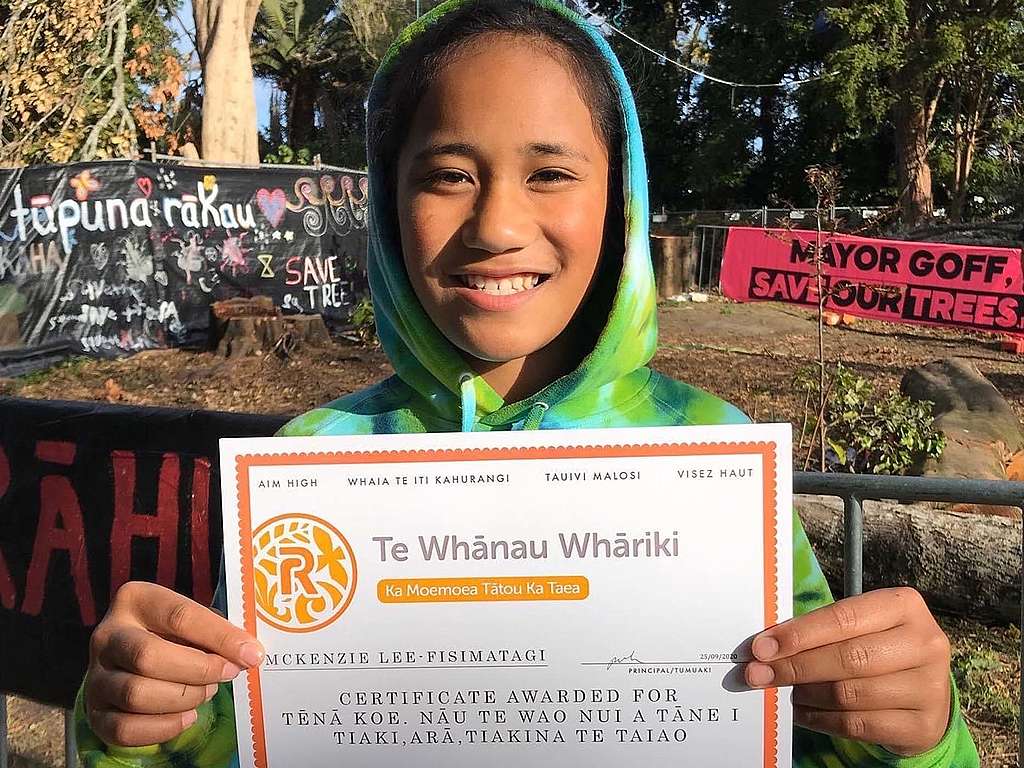

© Juressa Lee

About two years ago, my pōtiki climbed a pūriri tree with my hoamahi Zane and said, “I think trees should be the rulers of the world because they’re here before we’re born and still here when we go.” I asked him to keep talking to me when his feet were on the ground, eager to soak up his wisdom. I was so shocked by this beautiful and innocent insight, from a student on a Māori-medium education pathway who learns immersed in the Māori worldview. A worldview I’d been deprived of, but here was another push forward to acquire te reo me ona tikanga.

I heard the other day an expression that te reo Māori was the pathway to Te Ao Māori (the Māori world). This sums it up for me. Te Wiki o te Reo Māori is about creating space to reclaim and revitalise our language. Language revitalisation is a correction of colonial harm and validation of our position as tangata whenua. As we move through this pathway that te reo me ona tikanga provides, our tangata whenua status is legitimised and we move closer towards achieving tino rangatiratanga.