Hannah Stitfall is joined by submarine pilot John Hocevar to learn everything she ever wanted to know about what the ocean’s floor looks and sounds like.

We’ll also meet Quack Pirihi, who explains why they can’t be Maōri without the oceans.

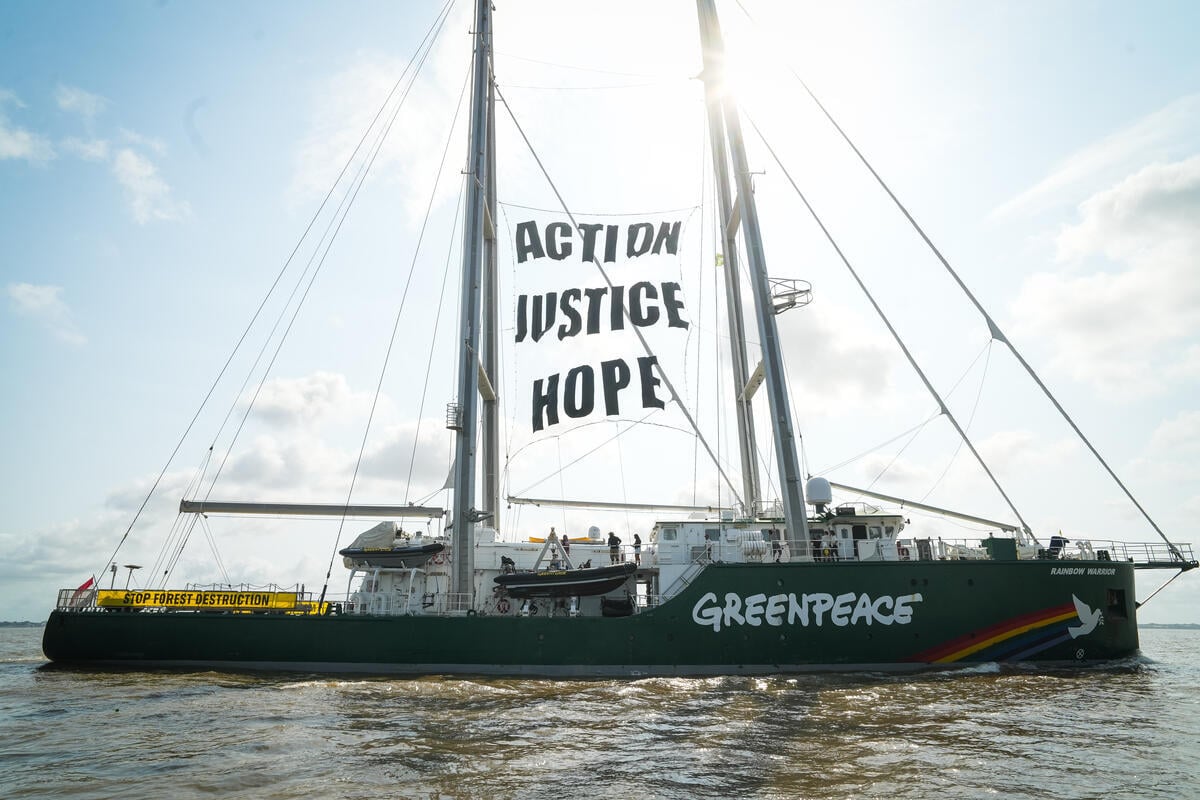

Presented by wildlife filmmaker, zoologist and broadcaster Hannah Stitfall, Oceans: Life Under Water is podcast by Greenpeace UK all about the oceans and the mind-blowing life within them.

Listen on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon Music or wherever you get your podcasts.

John Hocevar (Intro):

So first we’re testing out the submarine. So we’re on the deck with the submersible running through all the pre-dive checks making sure the sub is working. We close the hatches, at that point, we can’t actually get out of the sub on our own, we have to be led out. We get attached to the crane, dropped over the side release from the crane, move away from the ship, you know, water is sloshing over the dome and the sub is kind of moving back and forth. And then we start dropping down. So basically releasing all of the air from underneath the sub, and it gets darker and darker. It depends a little bit on where we are, it could get kind of blue or kind of green. Usually more at the surface you see little, you know, like fish. Sometimes I’ve seen seals and dolphins from the sub, which was amazing. But then as you get deeper and deeper, you know, 100 metres 200 metres, it starts to get much darker. Turn on our lights. So at this point, we’re only really seeing what’s kind of right in front of the lights. Off to the side, you might see beautiful, colourful flashing jellyfish or other types of bioluminescent creatures. One of our folks refers to them as disco jellies. But it’s not quiet, got static from the radio, there’s, you can hear the sound of the thrusters going worrying and, and you’re just trying to appreciate it all. But there’s all this noise. Usually as we get closer to the bottom is when we start seeing a lot more life. It could be krill, for example, in a little shrimp like creatures, or it could be the squid that often attacked us in the Bering Sea. I think people probably don’t realise just how important the seafloor is, in terms of where the biodiversity is concentrated. So the deep sea is most of the seafloor.

Hannah Stitfall:

This is Oceans: Life Under Water, a new podcast all about the oceans and the mind-blowing life within them. I’m Hannah Stitfall, I’m a zoologist, wildlife filmmaker, and broadcaster and I’m on a mission to learn everything I can about our five oceans, the Atlantic, Pacific, Indian, Arctic, and Southern. In this episode: The Oceans Deep.

John Hocevar:

It really is very much out of our world. And then also it is our world, right? The blue planet where we live.

Hannah:

People say we know more about the surface of Mars than we do about the bottom of the ocean. Is that true?

John:

We don’t know what’s down there. We don’t know the names of many, many, many of the species that live there, you could drop in almost anywhere in the ocean, and you could probably discover a new species.

Hannah:

This is Oceans: Life Under Water, Episode Two.

My guest today is a submarine pilot, explorer and campaigner. John has been exploring the oceans deepest, darkest corners for over 20 years, he has been face to face with some of the world’s weirdest creatures, and has even discovered an entire new species at the bottom of the ocean. And it gives me great pleasure to welcome him on today. Hello, John.

John:

Hello. Nice to be here.

Hannah:

Thank you so much for coming on. Where are you at the moment looks like you’re in a jungle!

John:

Feels like I’m in a jungle. But I’m actually at the Greenpeace International headquarters in Amsterdam.

Hannah:

Fantastic! So let’s get into it. I mean, there is a story that we know more about life on Mars than we do the bottom of the ocean. Is that true?

John:

I think it is. I mean, we’ve really just barely scratched the surface when it comes to understanding what is happening in our ocean. We don’t know what’s down there. We don’t know the names of many, many, many of the species that live there and we don’t know how they work together. We’re barely beginning to understand what we’ve done already and what we need to do to turn things around.

Hannah:

And of course, as a submarine pilot, I mean, you go very, very deep. I mean, what what is it like down there? What do you see, what do you hear?

John:

Every one of the things that I think is surprising to people is that every part of the ocean is so different. It’s really incredible being able to visit parts of it in a submersible. Each time we drop down, we really don’t know what we’re going to find. You never know what it’s going to be like. Is it going to be sand? Is it going to be a coral reef? Is it going to be…? Who knows? You know, it’s one of the things that’s so amazing about is just how rich and diverse and different the different parts of the ocean are.

Hannah:

How deep, what is the deepest you’ve ever gone to?

John:

I’ve only gone 600 metres. And I say only because the oceans are so much deeper than that. I think they go to, I have to do the miles to kilometres, but it’s about 12 kilometres. So you could drop all of Mount Everest into the ocean and still you’d have an enormous amount of water above it.

Hannah:

What is the deepest, deepest point of the ocean? And have have people been down there? And if so, what does it look like? And what’s the life like down there?

John:

The deepest part of the ocean is the Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench, and this is seven miles. So you know, 12-13 kilometres down. It’s just incredible pressures. Very, very cold, completely dark. And yet, there are still fish that live there, are still finding plastic trash there. There are only a handful of people that have been to this area. It’s really difficult. It’s a bit dangerous, pretty expensive. The Chinese sent a submersible down recently, a couple rich people have made their own efforts to make it down there. But I think it’s also worth saying it’s the deepest area that we know of, there’s still a real possibility that there’s somewhere deeper out there that we just haven’t found yet.

Hannah:

Absolutely. So you know, your job is incredibly important, I guess, for anybody listening to this who are obsessed with the oceans, like like we are. I mean, how do you even become a submarine pilot? How did you become a submarine pilot?

John:

Well, it’s a funny story. So I went to my boss, Lisa Finaldi, and I said, Hey, you know, I think we need to protect the largest underwater canyons in the world. And these are in the Bering Sea off of Alaska. And she said, Oh, that sounds interesting. I said, yeah. But to do that, we’re going to have to show people why they matter. We’re going to have to show people what’s at stake. Because the industry is saying there’s nothing down there, but mud and silt, and it doesn’t matter what they do. And she said, Okay, that sounds interesting. And I said, we’ll be able to use our ships. You know, Greenpeace has ships, which is pretty amazing and unusual. But I think we’re going to actually need a submarine to get down there. And she said, Oh, really? Somehow it worked. So that’s that’s how it happened. She, she let me go ahead. And it was about a four day training. So you know, if you could figure out how to drive a car, you could you could learn to drive a submersible.

Hannah:

Only four days training? I would have assumed it be longer than that to become a submarine pilot is a big deal.

John:

Yeah, you know, it’s not like, I’m not I’m not driving a nuclear submarine where, you know, there’s 1000 people on board this is usually they’re just one person or two people in these really small SUVs, like the size of a small car. So again, you know, if you figure out how to drive a car, you could learn to drive a sub.

Hannah:

Can you tell us a bit more about diving in Antarctica and also diving with some pretty famous people I’ve heard.

John:

Occasionally, in the submersible, I have some pretty famous guests, and one was Javier Bradem, the Academy Award winning actor.

Javier:

John, how are you my friend? What are you doing? I was the purpose of this submarine.

John:

We are using this submarine to gather data that will…

John:

Very, very nice guy really passionate about Antarctica. I think his maybe his first email address had penguin in it.

He just loves penguins. And so it was really cool to be able to bring him down to Antarctica. We’re on the ship for about a week together. Like we’re all just hanging out at night and talking, you know, telling stories. Javier Bardem stories are not like other people’s stories. It’s like oh, yeah, I was at this party with Mick like, Mick Jagger like yeah, okay. Alright.

Javier Bardem:

Some crazy person on board are asking if I want to go in there.

John:

I think you should come really it’s pretty cool.

John:

He wanted to go in the sub but still, you know, it’s a little bit, it’s a bit of a leap. And so he seemed a bit nervous about it.

Javier:

Like, I’d love to, but I don’t know, maybe I’ll stay on board.

John:

We’re like, oh, will I go, will I not go. We talked about it for a few days. Of course he went, you know, who would who would pass up the chance? He got very comfortable very quickly as we were going down. And then on that dive, we saw things that we still don’t know what they were, we have footage of things that were just weird looking! I mean, as a you know, as someone who’s spent a lot of time studying marine biology, it was still weird looking. I had no idea what we found. So that was cool. And he’s become such a powerful advocate for the oceans for the ocean treaty, you know, came to the UN and spoke directly to world leaders about why we need them to take action now. And he means it. You know, I think you talked about, you know, it’s easy to get cynical. I think a lot of people think why, you know, why is the celebrity saying this stuff about this thing? Do they really care? Or are they just trying to get publicity, the people that we tend to work with and Javier Bardem, for sure. It really is from the heart. And it was great to give him a vehicle where he could be so so effective, you know, use his voice and his following. And his, you know, his storytelling power to make a difference. And that was nice to be part of that.

Hannah:

I must just say as well, you’ve just let all of our listeners know that his first email address has penguins somewhere in it. So super fans, don’t go try find him an email him.

John:

Okay, that’s right. Yeah, let’s just let that go. Don’t get me in more trouble than I already am.

Hannah:

Do you ever feel claustrophobic?

John:

I don’t feel claustrophobic once I’m in the water. But when you’re in the sub, and they close the hatch, and they lock you in, it’s very small. And the top, you know, that dome is just maybe two inches over my head. So it’s pretty small. It doesn’t bother me. But I’ve definitely have talked to people that don’t like that feeling. But once you’re in the water that you don’t see the dome anymore. It’s it’s, it’s clear. So it’s just like you’re, you know, completely open to the ocean.

Hannah:

Now, tell us a bit about some of the creatures that live down in the deep because it really is, and it’s a shame because it is almost out of sight, out of mind. And that’s why your work is so important to teach people about what’s in the deep and why it is important. And I always remember learning about the angler fish, I remember that was the first deep sea creature I learned about and how the females are huge. And then the tiny little male in some species comes up and latches on to her and then he gets absorbed into her body. And that’s how they make little angler fish. And that totally blew my mind! But everything down there is it’s out of this world, isn’t it?

John:

It really is very much out of our world. And then also it is our world, right? So it’s, it’s, it’s hard for us to imagine what it’s like it’s so alien in many ways. And it’s it’s our, you know, it’s our planet, it’s the blue planet where we live. One of the surprising things about our ocean is that it provides about 90% of the habitat on our planet. So it’s very, it’s not just what’s on the surface, it’s three dimensional. So, you know, in a submersible, you experienced this a little bit like you’re at the surface, you’ve got light, you’ve got things that are floating on the surface of the ocean, and then you start to drop down, it gets pretty quiet, actually, you know, you lose light, it gets darker. Once you get further away from the surface, you’re usually seeing a lot less fish, a lot less things moving around. And then as you get towards the bottom, then you start seeing more and more stuff again. And then when you’re actually on the bottom, that’s where often it’s just teeming with life worms and clams and all kinds of mollusks and echinoderms, so things like starfish and then you’ve got fish that are feeding on some of these things and crabs and corals and sponges, all this stuff. You know, once you get out of these little thin bands, just you know what, 300 kilometres or so away from our shores, it starts to drop down and get pretty deep very quickly. This is where we know the least about what’s going on. It’s where probably most of our species live. And so far, it’s still the most pristine ecosystem on the planet.

Hannah:

Absolutely. And what would you say has been your most memorable encounter with the creature of the of the deep?

John:

Within the Bering Sea off of Alaska, and we’re at the bottom, you know, at this point, maybe it’s 500 metres or something. And there’s this Giant Pacific Octopus, and that’s the name of it. But it’s also giant, it’s a big, it’s a big octopus, and it’s bright, kind of orangey red. And it’s very cold down there, it’s maybe you know, three degrees Celsius. And the octopus is just kind of moving very slowly looking kind of sleepy. I’m just going to park this submersible right next to this octopus and just hanging out with this Giant Pacific Octopus. And we also discovered maybe the world’s largest skate nursery and skates are kind of like stingrays, there are relatives of sharks. There’s, again, near big canyons, which seems to be one of the places where skates like to lay eggs. But, you know, we’re just cruising along, and all of a sudden, the size of a football stadium, their egg cases everywhere and there’s skates, swimming and flying around and never seen anything like it. And it just makes you wonder, how do they know to come here? How do they find each other? How do they know this is the spot because from the surface, it looks like everything else. And no one knew was there until we stumbled upon it by mistake. If you were trying to discover a new species, if that was the point of what you were doing, you could drop in almost anywhere in the ocean. And you could probably discover a new species. So you’d be you know, dragging up a lot of mud probably especially and then just sifting through and finding what you’ve you’ve picked up, chances are really good that some of it is new to science. So especially and in the deep sea. Scientists are constantly discovering and cataloguing new species still at you know, 2024 we really, we’ve again, just really scratched the surface.

Hannah:

Well, they gave for all of our budding marine biologists listening in and if you want to discover a new species, this is this is the job for you.

John:

Absolutely right. That’s that’s the place to go on Earth. If you want to discover new species, the deep sea is where it’s at.

Hannah:

Have you ever seen a giant squid?

John:

I’ve never seen a giant squid, I would mostly love to I think a giant squid is actually something that could completely end a submersible expedition, I think a giant squid to be strong enough that it would pull bits off the sub, that we wouldn’t be able to replace. I mean, I don’t think we would be, you know, at personal risk or anything, but they’d probably pull the camera off or lights or something that we’d actually need to be able to function. So I would really love to see one but also, that’s the one thing that I kind of worry about encountering. Because, you know, it can take us months and months to plan one of these expeditions and you don’t want to end it before you’re ready to stop. And then giant squid could definitely end it.

Hannah:

And and how big do the giant squid get?

John:

I think the really big ones could be the size of a bus. At least as long as a bus and very, very powerful. There’s not a lot that we really know about giant squid or their cousins, the colossal squid. We usually only encounter them when they wash up on the beach or you know, we see we often see the evidence of them we see the scars from their tentacles on sperm whales, for example. They can be found certainly could be in deep water but also you know, they go where they want to go basically it’s kind of like great white sharks there’s, they go where they want to go, they eat what they want to eat.

Hannah:

And they’re the size of a bus.

John:

Hopefully, not the size of a bus. We’re talking about great white sharks. That would be terrifying. But yeah, the giant squid and big octopus one of the things I think that is so fascinating about them is the intelligence that’s there also with octopus the ability to change their colours and move in a way that can mimic something completely different from them. Not just another octopus, but a whole, like they could try to look like, anything they want really, I mean, they’re truly remarkable and almost distributed intelligence. So they, you know, we think about walking and chewing gum at the same time, they’re managing eight arms at the same time and also colour patterns across their entire body all at the same time, they can move in, you know, six or 10 different ways. They can walk and make it look like they’re, you know, walking on the bottom or they can swim or, it’s really hard to imagine what it would be like to be an octopus and what it would take to think and move and operate like an octopus and that’s, that’s fun to think about.

Hannah:

I mean, cephalopods in general out there they are, they are otherworldly group of species. And I just want to say to our listeners, we’ve actually got a full podcast episode coming up all about octopus, it’s gonna be exciting.

Hannah:

A quick little message for me if you’re enjoying this series, and I really hope that you are, help us out by hitting the Follow button. Do check us out on socials, we’ve got some amazing video content on TikTok, Instagram, and X/Twitter. And if you want to see what it looks like to go down in a submarine, come and join us at oceans pod.

Before we get back to John, I’ve got a question for you. Can you actually picture how deep the oceans really are? It’s pretty hard. So here’s Helen, my guest from our last episode to help you out.

Helen Scales:

Let me tell you just how incredibly deep the ocean actually is. I want you to imagine that we’re going to sail offshore together in a beautiful sailing yacht to a part of the ocean where it’s very, very deep. And we’re going to take a normal glass marble, I’m going to drop it over the side of the boat. And we can follow that marble on its journey down through the depths. And in fact, the deep ocean is divided up into different areas, different zones. The top is the sunlight zone, the part where the sun is still shining. It’s the top 200 metres and it’s going to take our marble about six or seven minutes to drop through that bit. Then the marble will reach the twilight zone. This is the part where all around us the light is very deep blue is the last remnants of sunlight of just making their way down into that zone. The marble is going to pass through the twilight zone for about half an hour. And then it’s going to reach the midnight zone that’s at about 1000 metres down. And this is where there’s no sunlight at all. All that light coming down from above has been absorbed by the water, it’s permanent midnight in this zone. That’s gonna carry on down to about 4000 metres, it’s gonna take about an hour and a half to get through the midnight zone. Our marble’s falling all the way down and down. It’s gonna keep on going. If we’ve positioned our yacht in a good place above one of the deepest parts of the ocean, which are the oceanic trenches, the big chasms in the bottom of the sea, if we could get our marble into one of those, and possibly the deepest, which is the Mariana Trench in the Pacific, is going to have to carry on down to almost seven miles. That’s the deepest point 11 kilometres just about, it’s gonna take our marble from the surface falling all the way through the sun zone, twilight, midnight, into the hadal zone, which is what that last bit is called. It’s gonna take six hours, six hours from the top to the bottom to very long way down to the bottom of the sea.

Hannah:

So John, can you tell me a bit about the thermal vents at the bottom of the ocean?

John:

When I was probably 16, I wrote a paper called ‘stuff lives where there’s food’. And it was about hydrothermal vents.

Hannah:

Excellent title!

John:

Our oceans are expanding in some areas and and contracting in others. And the hydrothermal vents are basically where the sea float new seafloor is being created. So you have this really hot magma and gas at the bottom of the ocean. And it can form these magnificent chimneys and almost cathedral like structures. And what’s so fascinating about these areas is that it’s a whole food web that is not dependent on the sun. So most, even in this, even at the bottom of the ocean. A lot of the food there originally came from the surface and so you know it started with phytoplankton and plant ants that turned sunlight into food. And then you know things ate them and things ate those other things. And they decayed and get chewed up, and then they sank to the bottom. And this is different, this has nothing to do with the sun, the sun, if the sun didn’t exist, this whole ecosystem would still be there. And in this very superheated water that’s coming out of these vents, you have high portions of metals that then are turned into food, by bacteria. And so when they first discovered the hydrothermal vents, they they encountered these weird, really big worms and clams, not just new species, but new classes of, new phylum of species, of creatures. And they feed on these micro bacteria that are only found in these vents. And so it’s this whole new ecosystem that’s thriving, and it’s got nothing to do with the sun or or plants. It’s wild.

Hannah:

That is incredible. I can’t even comprehend it. There’s a whole ecosystem that is totally unrelated on on the sun.

John:

It’s amazing stuff. But that hasn’t stopped some mining companies from wanting to go and cut off the tops of these chimneys, and you know, these underwater cathedrals and sell them, you know, maybe for nuclear missiles.

Hannah:

What is wrong with them? Can’t they do something else, you know, just, just leave them alone.

John:

It doesn’t say good things about humanity, that we come up with these ideas. And it doesn’t really say good things about our governments that they would allow, whether they would entertain an idea like that. I mean, this seems clearly like something that we should just stop before it gets going. Fortunately, there are quite a few governments at this point that have already said, Look, we need at least a moratorium on deep sea mining. We have a lot of questions to answer before we’re going to allow that to move forward.

Hannah:

And you’ve been part of the Rebuild the Oceans campaign for for 20 years in that time. How have you seen the oceans change?

John:

But when I was in grad school, we had I was studying coral reefs, we were not talking about bleaching. That wasn’t even really a thing yet. So seeing just how quickly, coral bleaching driven by warming oceans during by climate change has devastated reefs all over the world is been hard to cope with.

Hannah:

And that’s in a relatively short period of time as well.

John:

A very short period of time. I mean, you know, certainly in my lifetime, but even just a part of my lifetime. But beyond that, I’d say another really big change is the impact of plastic. It doesn’t matter what they study, but every type of marine biologists or oceanographer is encountering plastic. I talked to coral scientists that I wasn’t thinking about plastic, I was trying to figure out what my corals were eating. And then I saw that they were eating, what is this stuff? Oh, my God, they’re eating plastic, you know, his little bits of microplastic. And she even found that they were preferentially eating plastic that the corals would choose plastic over something that was actually food. And then she became, you know, kind of a plastic expert, and she didn’t want to be. But it’s just there’s so much plastic that we’ve put into our world that if you’re studying the world, you’re studying plastic.

Hannah:

I mean, plastics even been found in the Mariana Trench, hasn’t it?

John:

That’s right. At this point. It is literally everywhere that we look, expeditions that I’ve been a part of, you know, we’ve been to the big trash for Texas, in the Pacific and the Atlantic. But also we, you know, we go to places, we hope there won’t be any plastic. You go to the tops of mountains, we go to the Antarctic, it’s in the snow and Antarctica. It’s we saw lots of it in the Arctic, there’s there’s really nowhere to go on Earth where you won’t find plastic at this point.

Hannah:

So John, you’re a little bit of a superhero thing. I mean, you know, you’re a submarine pilot, you’re a campaigner. You’ve discovered new species. Dare I ask, what are you working on right now?

John:

Oh, my God. So we are going to end deep sea mining before it starts. So we think about all these huge issues can be pretty overwhelming. You know, climate change, deforestation, overfishing, problems that took us decades or hundreds of years to create. It can feel pretty overwhelming to try to stop that. We still have to do it. Deep sea mining though. This is something that it’s a terrible idea that we haven’t started doing yet. Companies want to go out and mine the world’s most pristine ecosystems, the deep sea for these rare metals, we don’t actually need to do that. Just thinking about all the things that we have to deal with on this planet already. The idea of starting a whole new terrible industry, let’s let’s not do that.

Hannah:

Bad idea! It’s a really bad idea.

John:

It’s a bad idea! I think we can agree on that. It’s a bad idea. We are also making sure that our fisheries are not harming the environment or not, you know, incidentally, killing hundreds of 1000s of turtles or a 100 million sharks a year, for example. But also that our fisheries are not enslaving people are not exploiting to people where they can’t feed themselves, never mind their families. So we’re fixing we’re working on fixing that.

Hannah:

And what would you say? What are your hopes for the future of the ocean? So you know, what would? Where would you like them to be say in another 20 years from now?

John:

Another 20 years from now, we will have definitely protected more than 30% of the world’s oceans. The big answer is that we have much healthier oceans that are more resilient, better to survive all the other things that we’re still doing. And we have healthier coastal communities. We have healthier island communities because the oceans are are doing well.

Hannah:

Well, myself included and I’m sure all of our listeners will agree with you on all of those points. But thank you, John, for coming on today in your in your jungle background there. It’s been lovely to talk to you and keep up the fantastic work.

John:

Thank you very much. It’s been a pleasure.

Hannah:

That’s it for this episode. Next week, Whales. If you want some more though, stick around for our closing story. You’ll hear from someone who lives or works near on or in the oceans. This week, we’re going to New Zealand.

Quack Pirihi:

Tena koutou katoa. Greetings to you all. Ko Quack Pirihi toku ingoa. My name is Quack Pirihi and I am a 21 year old cheeky rangatahi, cheeky youth, that is living in Aotearoa, also known as its colonial name New Zealand. Tikanga maori, in the Maori culture, we have a whakataukī or phrase that’s called Ko ahau te awa ko te awa ko ahau. I am the river and the river is me. The ocean is important to Maori because without it we cannot thrive. Without an ocean to mark where our ancestors arrived or where our ancestors travelled, we are lost and we are stranded on foreign land that we are unsure on how to connect to.

I grew up in a place called Pamua, which didn’t have the best waterways growing up. I don’t know how they are now. But all we had was a little wharf on the Tāmaki river to connect to which was often polluted and I didn’t know how to swim growing up. And so there are all these little things that acted as as barriers for me to connect to the to the moana, to the ocean. But growing up, I’ve been lucky to travel to different places within New Zealand to explore the ocean. I’ve been lucky to learn the stories of different iwi, different tribes, about how their ancestors lived off the ocean.

One of the biggest streets I see to the protection of the ocean is deep sea mining. Deep sea mining is a stain on the rights of indigenous people not just within the Pacific but also all around the world. When I think of my personal connection to the ocean, I think of the deep, dark frightening responsibility to protect this body of water that has fed generations around the world for 1000s of years. That makes no sense why someone would want to destroy it. My name is Quack Pirihi, and I am a kaitiaki, a caretaker of the ocean

It’s time for New Zealand to take a stand. Join our call on the New Zealand government to back a global moratorium on seabed mining.

Take ActionThis episode was brought to you by Greenpeace and Crowd Network. It’s hosted by me, wildlife filmmaker and broadcaster Hannah Stitfall. It is produced by Anastasia Auffenberg, and our executive producer Steve Jones. The music we use is from our partners BMG Production Music. Archive courtesy of Greenpeace. The team at crowd network is Catalina Nogueira, Archie Built Cliff, George Sampson and Robert Wallace. The team at Greenpeace is James Hansen, Flora Hevesi, Alex Yallop, Janae Mayer and Alice Lloyd Hunter. Thanks for listening and see you next week. Transcribed by https://otter.ai