It has been sixteen years since the World Health Organisation (WHO) last updated its air quality guidelines – the last update being in 2005. These guidelines provide an assessment of the health impacts of air pollution, and thresholds for harmful pollution levels. On 22 September 2021 WHO provided a revised version of its air quality guidelines.

Since the inception of the WHO Air Quality Guidelines in 1987, scientific understanding of the health risks of polluted air has expanded. Evidence has mounted that even low-level exposure to air pollution is harmful to humans, especially with chronic exposure. It is increasingly evident that there is no safe level of air pollution. The WHO renews its guidelines to reflect developments in our understanding of the threats and risks from air pollution.

Cities around the world, including Johannesburg, are locked into an air pollution crisis. Among the most deadly pollutants circulating in the air is PM2.5 – particles with a diameter of less than 2.5 micrometres. Microscopic sulfate particles are released by coal combustion which are small enough to enter the bloodstream. PM2.5 exposure is known to cause a myriad of health problems, including strokes, heart disease, lung cancer, and both chronic and acute respiratory diseases, including asthma.

In 2020, at least 79 of the world’s 100 most populous cities had annual mean PM2.5 pollution levels that breached the 2005 WHO Air Quality Guidelines, according to data published by IQAir – a Swiss air quality monitoring company. This statistic is based on city-wide averages; hotspots within all 100 cities likely exceeded the guideline locally.

The Covid-19 pandemic slowed down economies across the globe reducing the use of fossil fuels that pollute the air. Despite the drop of air pollution in most countries, including South Africa, we have seen our air quality skyrocketing back to dangerous levels as economic activity recovers with the relaxation of lockdown restrictions.

Air pollution is a major environmental risk to health. According to IQAir, 92% of the global population is exposed to dangerous levels of air pollution, and many places lack measurements to quantify its effects and allow communities to respond effectively. What is most frustrating is that the lived experiences of people living in coal-impacted regions are discounted because of poor monitoring structures – air monitoring stations. Residents of coal-impacted regions report a host of health problems related to air pollution, yet the government’s favouring of polluters interests leaves them with little relief.

The health impacts also take a financial toll. Work absences due to sickness and lost life years due to premature death are accompanied by a substantial financial cost to society of up to 14% of total GDP in some locations. Implementing air pollution standards that favour people’s health over the bottom line of companies like Eskom and Sasol is a no-brainer for reducing the burden of disease related to air pollution from burning fossil fuels. In big cities like Johannesburg, pollutants mainly come from incomplete combustion processes in road traffic, industrial plants such as cement processing plants and smelters, and coal power plants – in and around the city.

On the other hand, methane and ozone also have an impact on climate change. We must remember that climate change is no longer an event in the distant future. Indeed, we are watching it unfold before our very eyes, as extreme weather events are becoming more unpredictable. Reducing these pollutants is also key for climate change mitigation.

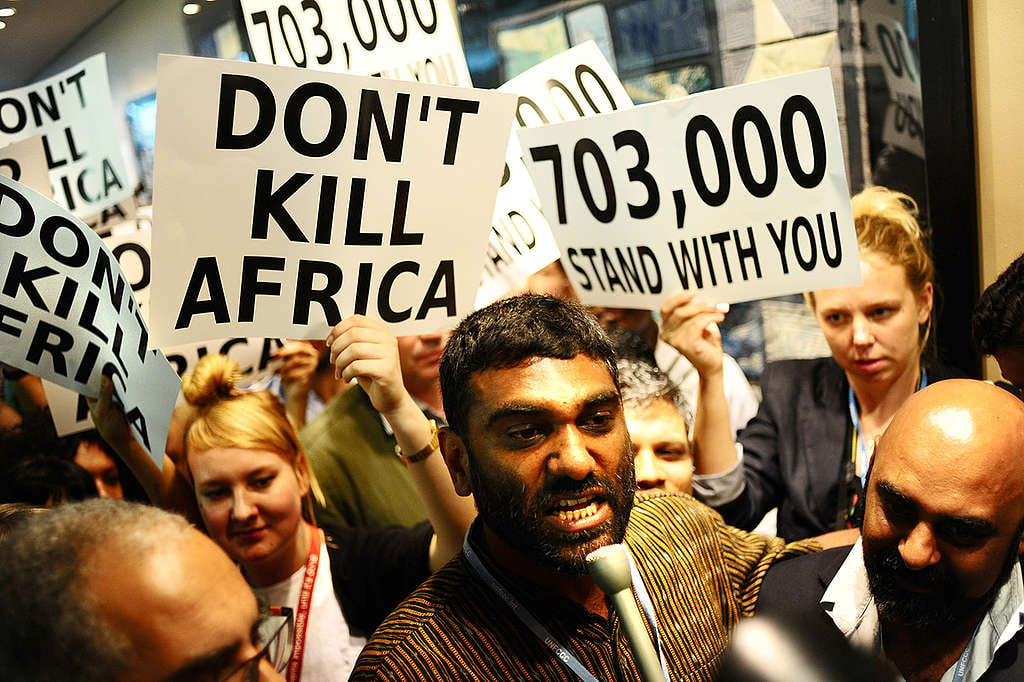

The WHO’s updated Air Quality Guidelines are a firm warning about the severity of the air pollution crisis. Governments around the world must take bold action to ensure their cities turn from sources of air pollution-related health risks to safe places for billions of humans to reside.

Firstly, in the case of South Africa, the national government priority should be to urgently seek alternatives to burning fossil fuels for power, transport and industry because burning coal, oil and gas are major sources of the global burden of disease and mortality from air pollution.

Secondly, South Africa should be encouraged to prioritise provision of transport infrastructure that revolves around walking and cycling – or for longer distances to upgrade the existing public transport system, providing safety, so as to reduce the number of vehicles on roads, reducing the use of fossil fuelled modes of transport.

Finally, communities should be empowered with information on air quality regularly. They should be given clear solutions to the consequent health and financial problems of air pollution in respective regions (whether urban or rural). The governments must lead with policy and system-wide changes, while supporting communities by taking steps that will improve their quality of life. Major polluting industries must be made to account for the deteriorating air quality in their operational areas, especially companies like Eskom and Sasol.

South Africa should demand that Barbara Creecy, Minister of Forestry, Fisheries and Environment, revise the weakening of the minimum emission standards to avoid further increases in the heightened levels of SO2 incidents, such as those that occurred in Johannesburg and Pretoria at the beginning of 2021.

The country should boldly call for the South African government, banks and other investors to halt all investments and subsidies on fossil fuels and shift to safer renewable energy sources such as wind and solar.

With UNFCCC COP26 approaching towards the end of 2021, South Africa should up its ambition in dealing with the dual crises of air pollution and climate. People deserve to breathe clean air, and we cannot afford to be derailed from meeting our commitments to the Paris Climate Agreement to limit global heating to 1.5oC. All of our futures depend on it.

Get Involved

Get Involved