In order to understand the relationship between gender and climate change, it is important to have a clear idea of what gender is. ‘Gender’ and ‘sex’ are sometimes used interchangeably, they are in fact distinct concepts. While a person’s sex refers to their biological characteristics, gender is a socially constructed classification that describes social and emotional attributes and ascribes qualities of masculinity and femininity to people. Gender characteristics tend to be different between cultures.

In the context of climate change, gender role expectations and gender inequality affect individuals’ vulnerability, resilience, and adaptive capacity. Tasks core to survival, such as collecting water and wood or growing food, fall on women in many cultures. These are already challenging and time-consuming activities; climate change can deepen the burden, through water scarcity and drought.

The climate crisis thwarts the rights and opportunities of women and girls, as well as non-binary people who do not identify as man or woman. These realities make gender-responsive strategies for climate resilience and adaptation critical. And they mean that bold climate action is critical to our aspirations for gender equality and justice. According to the United Nation’s Development Programme, as the climate crisis worsens, pre-existing gender inequality may also worsen. Despite this increasing evidence that women are more vulnerable, climate change policies, frameworks, discourses and solutions are rarely gender sensitive. Now is the time to challenge this.

Moreover, climate change is a powerful threat multiplier, making existing vulnerabilities and injustices worse. Women and girls, as well as nonbinary people, particularly from poor communities, are at greater risk of experiencing the adverse effects of climatic changes. This risk and vulnerability to climate change impacts may also be attributed to interlinking social, economic, cultural, institutional and discriminations that contribute to these groups’ restricted access to natural resources, decision-making spheres and information that help build adaptive capacity to climate change.

Consequently, it is important to note that if adaptation initiatives to address climate change effects do not adequately address poverty and sustainable development, they run the risk of increasing gender and social inequalities.

The impacts of climate change and on gender-based violence

The social, financial and infrastructure stresses that come with natural resource scarcity – and that particularly arise or are reinforced during and in the aftermath of weather-related disasters and climate change – can augment unequal household gender dynamics, contribute to resource grabbing and spark incidences of gender-based violence.

It is essential that we recognise that these incidents of sexual and gender-based violence threaten women’s lives and impede their ability to carry out vital livelihood activities, such as accessing their fields or going out to seek employment. As our nations work on effectively adapting and building resilience to and mitigating climate change and climate-related effects, they’ll do well to note that they will require gender-responsive approaches, which recognise the importance of GBV and the GBV- environment linkages by developing and adopting institutional policies, strategies, plans and other mechanisms to address them.

To ignore this dimension suggests a vicious cycle. The risks include further increasing incidence of GBV, which in turn impacts health and security of women and their families, making them more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change and weather-related disasters, and further entrenching households and communities in poverty.

Violence against women environmental human rights defenders

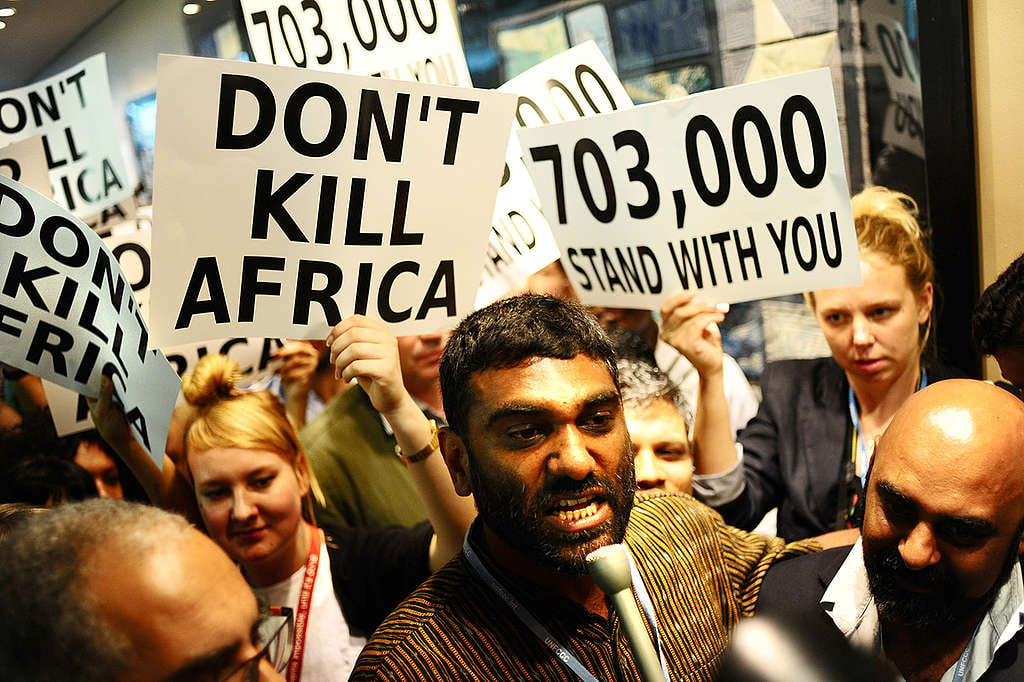

Although women are showing remarkable resilience around the world, the threat that they are met with as they lead climate action movements and championing clean sources of energy, is a widespread issue we simply cannot ignore. Women environmental human rights defenders experience differentiated expressions of violence as means for control. According to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), from 2015 to 2019 human rights defenders have been killed in at least 64 countries—a statistic which proves that the issue of the killing of human rights activists is not endemic to one region.

In South Africa for example, the brutal murder of Mama Fikile Ntshangase has raised concerns regarding the risks environmental activists face because of their work and on the attempts to silence them. The murder of Mama Fikile should not be considered an isolated incident. Her death is part of a rising tide globally of violence against environmental activists.

As South Africa recognises and commemorates women’s month this August, it is crucial that we bring to light some of the issues faced by women environmental human rights defenders. Furthermore, policymakers must take gender into account, in order for nations to ensure that climate change initiatives alleviate, not exacerbate, gender-based oppression. It is important that they ensure equal space and resources for women and men to participate in climate change decision making and action at all levels.

Gugu Nonjinge is a Senior Advocacy Officer at the Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation

Get Involved

Get Involved