As the plane from Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), makes its descent towards Mbandaka airport, the capital of Equateur province, I am impressed by a beautiful canopy of greenery painting the landscape below my window; I was looking at the Congo Basin Forest. A casual observer sees a forest, robust, full of life. But I know it is a fragile forest that could lose one of its best protection measures soon if we do not fight for it.

After the war in the DRC in 2002, under pressure from the World Bank, the Congolese government suspended the award of new industrial logging concessions. A primary objective of this moratorium (a temporary stop until certain conditions are fulfilled), was to embark on a path whereby the forest sector would become a sustainable industry, generating billions of dollars in revenues and tens of thousands of jobs.

The moratorium has remained in place for the 15 years since due to inaction on participatory zoning on potential concession areas; failure to establish a three-year rolling plan indicating the exact number, areas and locations where concessions would be gradually awarded; and failure to build institutional capacity to regulate, monitor and control commercial forestry.In that time it has continuously helped to preserve Congolese forest and prohibits the expansion of logging concessions. That the moratorium is under threat is an alarming but painful truth. In 2015 breaches to the moratorium by Congolese government officials were uncovered. These officials are bound by the moratorium because the preconditions for lifting it have not yet been fulfilled, but they would rather get rid of it. If the moratorium is lifted it would put at risk the habitat of threatened species and the chance for forest communities to manage their livelihood.

In July 2016, Greenpeace exposed the awarding of illegal concessions by then Environment Minister Bienvenu Liyota and in February 2017 exposed two further illegal concession awards in September 2016 by then Environment Minister Robert Bopolo.

Bopolo subsequently admitted he had signed three concession contracts, and alluded to the existence of even more illegal awards. Minister Athys Kabongo Kalonji announced he would cancel all the illegal concessions awarded by his predecessor, but the cancellation orders still have not been published.

It remains unclear whether other people in addition to Bopolo and Liyota were also involved in concealing the illegal allocations. No investigation has been initiated and no sanctions taken against those involved. Not only are those involved in these illegalities are not held accountable, at least one has been promoted!

Donors of the Central African Forest Initiative (CAFI), which aims to protect the Congo forest to reduce carbon emissions from deforestation and forest degradation, requested the immediate cancellation of these illegal awards. More than three (3) months after the exposure, the DRC government still hides behind vagueries.

These same donor country governments also seem to believe that industrial logging could actually be part of the solution. An expansion of the logging sector and the lifting of the moratorium is considered by them as credible option to reach the CAFI initiative’s objectives. Greenpeace, as well as a significant part of the global scientific community, considers this option fundamentally incompatible with the goals of reducing forest degradation and deforestation.

I was heading from Mbandaka to Imbonga village to meet local partners. The village’s only route is a twelve hours journey on a fast boat on the Congo River. Although illegal under Congolese law, large quantities of logs abandoned by bankrupt logging companies can be seen in some villages on the way to Imbonga. Working for a campaign organisation that bears witness to environmental destruction, I realised the delicate nature and what’s at stake to protect the Congo Basin forest.

Villages are in conflict with industrial logging companies because there is little or no dialogue between the parties and minimal trickle-down gains from logging revenue. Community Forestry offers the opportunity for local and indigenous people to control and manage the forest in a sustainable way, but once the moratorium is lifted, new industrial concessions will very likely be in direct competition with these community projects.

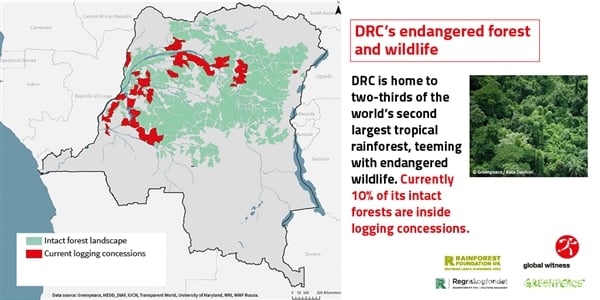

The Congo Basin forest boasts impressive Intact Forest Landscapes (IFL); forest ecosystems which show no remotely detected signs of human activity and can maintain all native biological diversity. The forest is rich in plants and animals unique to the region like okapis and lowland elephants. This forest also boasts the world’s largest tropical peatland. Lifting the moratorium could put the existence of critically endangered animal species, such as the bonobo, at severe risk. It also threatens the peatland, which in the fight against climate change must be left intact.

As our plane flies out of Kinshasa’s night sky, the darkness outside my window makes me realise the limited reach of electricity supply in DRC. With basic infrastructure and limited social amenities, I ask myself what rewards has industrial logging brought to the people? Why would one want to lift the moratorium without adequate safeguards to manage forest resources and who are the real beneficiaries of logging?

_____

Stand up for forests, sign the petition here!