There’s an important line in the Paris climate agreement which says:

“[The Paris climate agreement] aims to strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change… by holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels.”

Basically, the world needs to get more ambitious when it comes to limiting global warming.

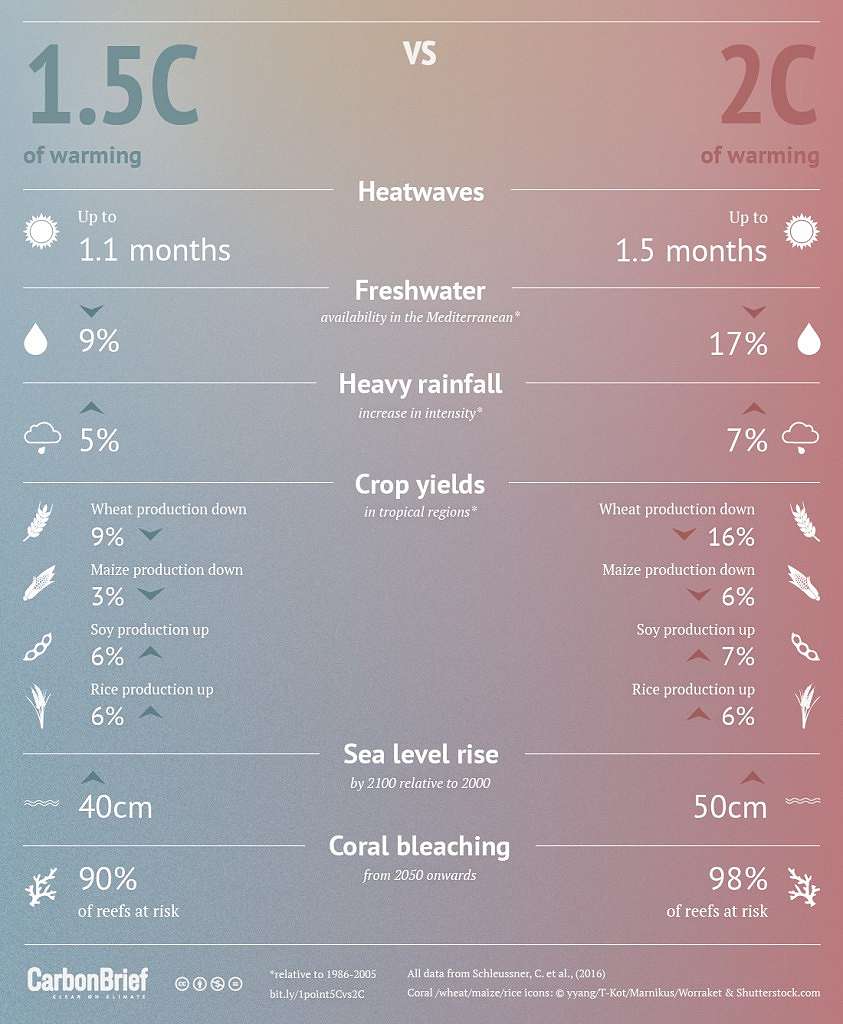

Though the difference between 1.5°C and 2°C might not seem like much, that half a degree difference really stacks up – as this neat-looking infographic explains.

1.5°C of global warming vs. 2°C – a snapshot of the difference in impact. Source: CarbonBrief

Since the Paris climate talks in 2015, scientists and researchers have been busy turning that 1.5°C target into something more meaningful, like working out how quickly we need to stop burning coal and oil, how many wind and solar farms we need to build, and how soon we need to switch from gas guzzling cars to zero-emissions vehicles.

In a new study – commissioned by Greenpeace and carried out by Germany’s Aerospace Centre – researchers set out to shine a light on one of the big questions that falls out of the 1.5°C target: ‘How soon do we need to stop the sale of new fossil fuel cars?’

And the answer is: pretty damn soon.

Rush hour in Beijing

The car conundrum

For the climate to stay under 1.5°C of warming, every industry you can think of needs to start making radical changes. From companies that produce electricity, to construction firms that build our homes and offices, through to the big food and agriculture firms that oversee so much of the food we all buy – these industries make up the bulk of the global economy, and they all need to play their part in transitioning from a high carbon world to a low carbon one.

Getting every industry on the planet to change its business practices might seem a little daunting, but in some sectors it’s already happening.

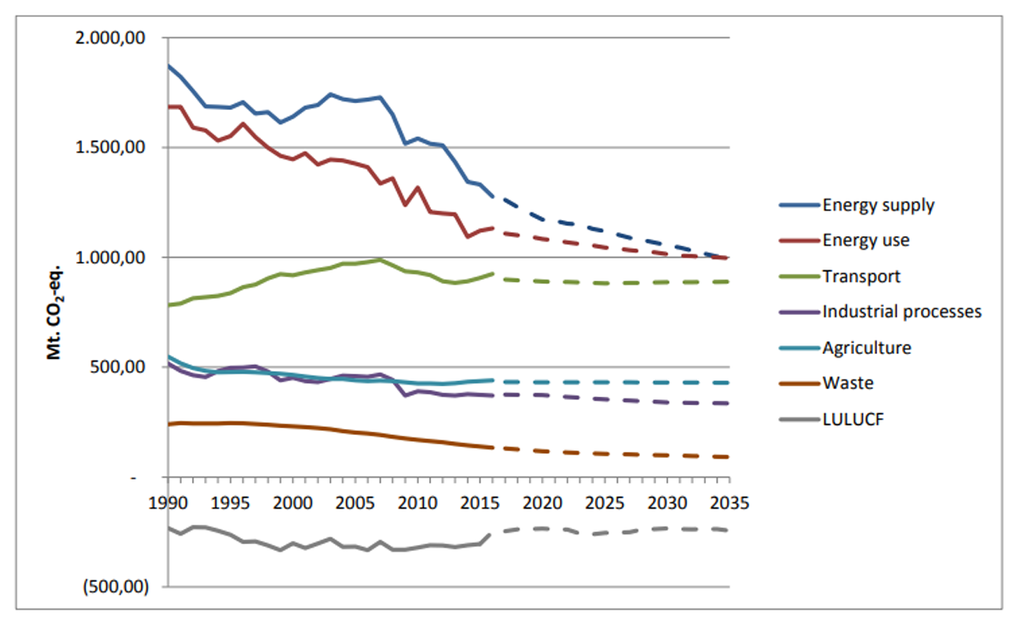

EU greenhouse emissions per sector. Transport emissions have risen in recent years and predicted to flatline. Source: European Commission.

EU greenhouse emissions per sector. Transport emissions have risen in recent years and predicted to flatline. Source: European Commission.

Take the electricity sector, where thousands of wind farms and solar panels have been installed over the last decade. Wind, solar and biomass now supply more than 20% of electricity generated in the EU, up from less than 10% in 2010.

But it’s a different story when we look at transport.

Transport is the only major sector where greenhouse gas emissions have gone up in recent years, with rising car sales and a soaring demand for larger vehicles (like SUVs) driving the problem.

With the automobile industry quite literally steering plans to tackle climate change in the wrong direction, some governments are now talking of forcing them onto a path that’s better for the climate. Like the UK and France, who are discussing plans to ban the sale of new petrol and diesel vehicles by 2040.

But with 2018 being so scorching hot that wildfires broke out across the northern hemisphere, this year’s weather raises the question: can we really wait for these proposed bans to fix things?

Wildfires swept through California this summer

2028 deadline

To answer this question, the German researchers began by charting what they think will happen naturally to the car industry, without new laws to force car firms to change. Their predictions factored in the fact that, due to public concerns about the health impact of diesels, the sale of diesel-powered cars is already falling dramatically.

Next, the research team calculated the ‘carbon budget’ that can be attributed to the transport industry (the amount of CO2 that can be pumped out while keeping warming below a certain temperature threshold).

What they found is that, without laws to drive change, the rate at which electric vehicles will be introduced to the market won’t be enough to stop the industry blowing through its carbon budget.

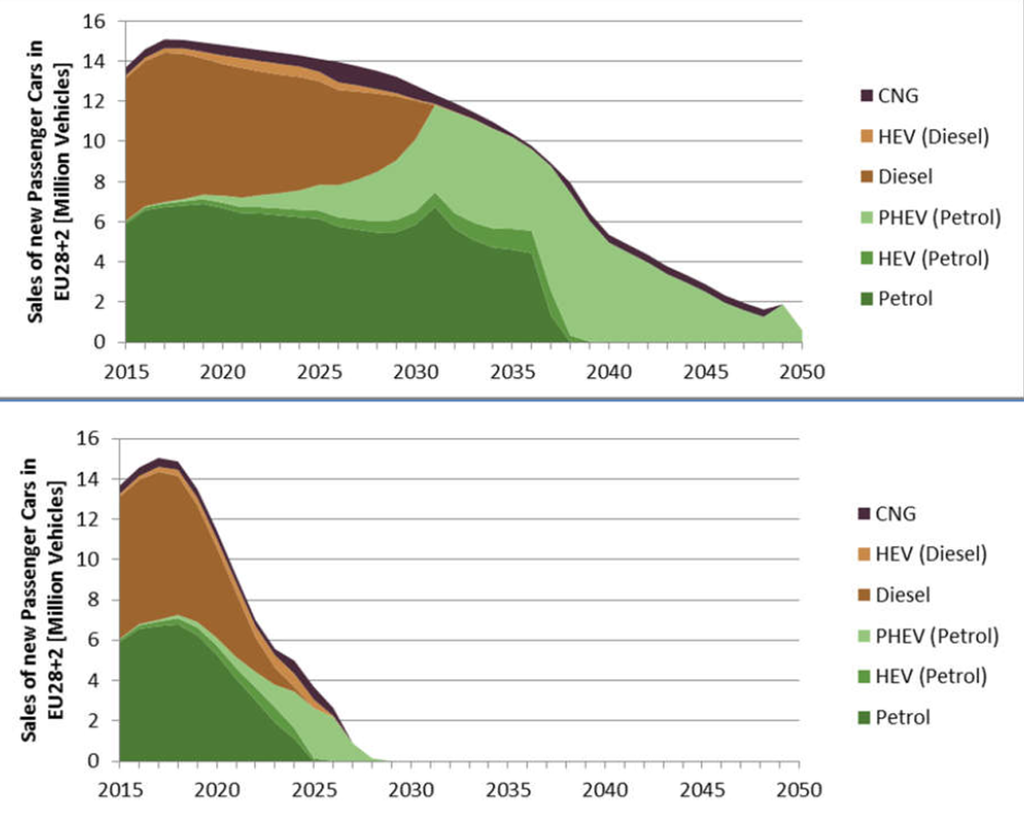

The two graphs below sum things up. The top one shows what the researchers think will happen over the coming few decades unless any action is taken. The bottom graph shows how much faster the sale of diesels, petrols and hybrid engines need to decline if we’re going to have a decent chance of hitting the 1.5°C target.

Top: DLR’s current projection for new car sales in Europe. Bottom: target car sales for a 66% chance of staying under 1.5°C of warming. Source: DLR

Looking at the bottom graph, we can see that the sale of new high emission vehicles needs to fall to zero by around 2028. That means we’ve got about a decade to completely ban the sale of petrol and diesel vehicles.

At this stage we should also state the research only looks at the car industry in Europe, and not vehicles in Asia and the Americas. More research is need to cover these regions. And it’s entirely possible that some countries would need to phase out fossil fuel cars even quicker.

The Norway model

So how realistic is it do this by 2028?

It’s estimated that by the end of 2018, only 2.35% of new cars and vans sold in Europe will be electric. So switching the entire industry from being a high carbon one to a low carbon one, might seem like an impossible task in 10 short years.

But here’s the good news; Norway is showing how fast things can change.

In Norway, a combination of tax incentives and government policies are driving staggering electric car growth. So much so that the Scandinavian country has set 2025 as the goal for all new cars to have zero emissions.

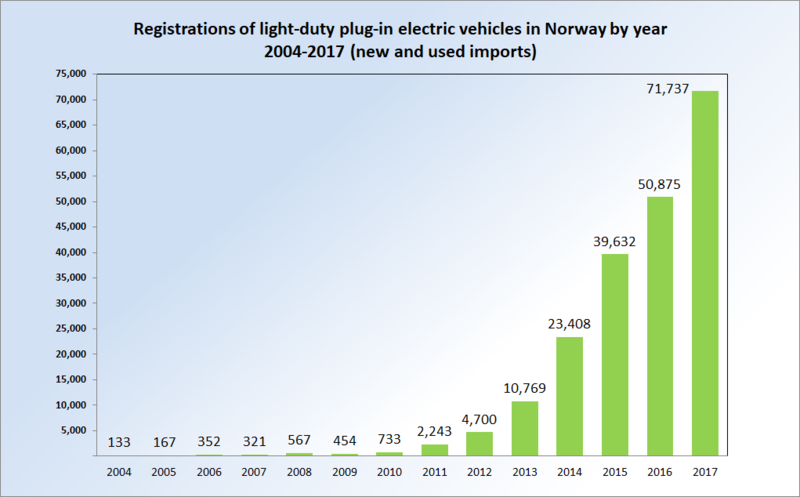

Norway has the world’s fastest electric car growth. Source: Wikipedia

Norway has the world’s fastest electric car growth. Source: Wikipedia

We need to think beyond cars

Cutting pollution from transport doesn’t only have to be a choice between fossil fuel power cars and electric ones.

A truly sustainable plan for transport should be about constructing more bike lanes, building cycling infrastructure that would make it easier for people to get around without cars. It should be about making public transport more affordable, leading to more people using trains or buses to get around. And it should be about investing in car sharing schemes, and reducing the amount of vehicles on the road.

Following such a path would be a sensible for a whole raft of reasons. It would mean reduced pressure on natural resources, as fewer cars would mean less demand for steel and plastic used to build vehicles.

It would mean a quicker route to cleaning up our air, as more polluting cars could be taken off the roads sooner.

And most of all, it would mean an even greater chance of keeping under 1.5°C degrees of warming.

Richard Casson is the digital engagement lead of the air pollution campaign